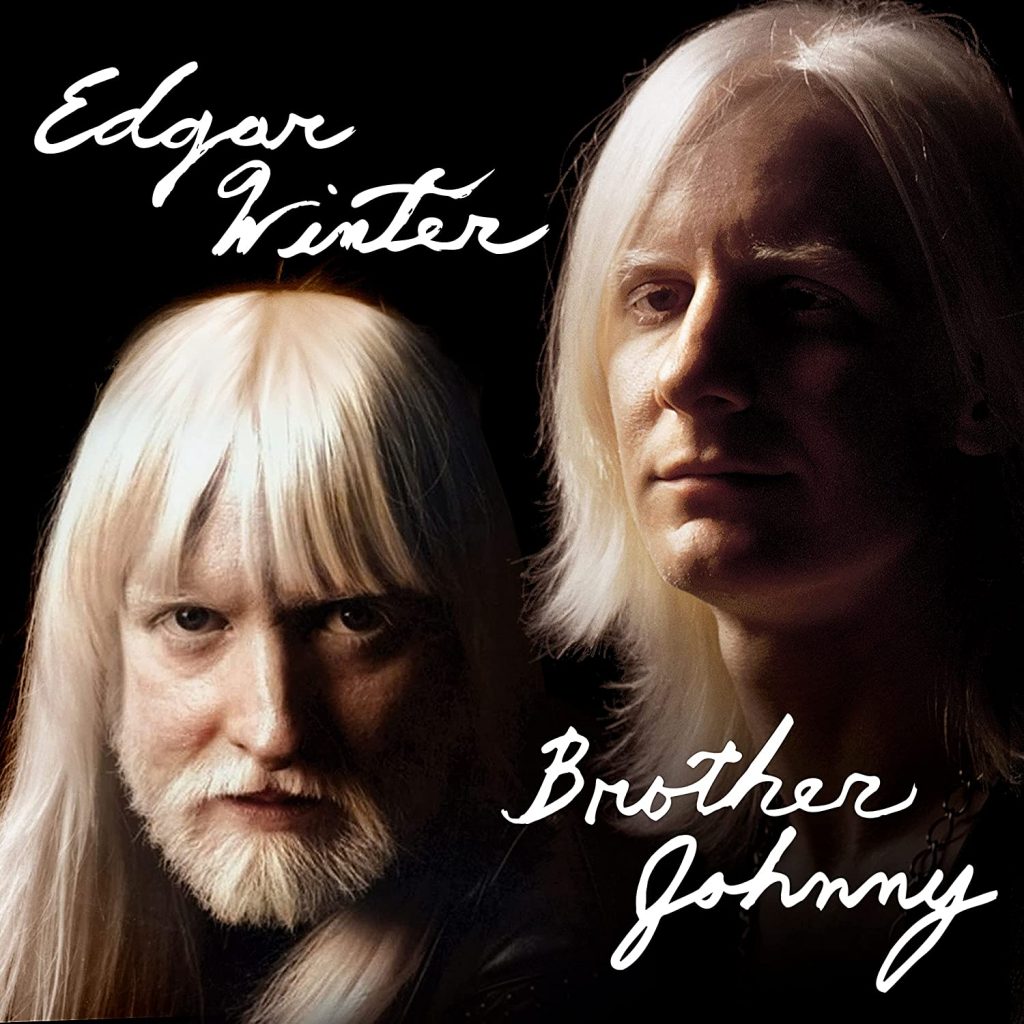

Is Edgar Winter a bigger talent than his more famous late brother? Merely contemplating such an idea has been considered sacrilege for more than half a century. Most blues and rock fans didn’t even know that Johnny Winter had a younger brother until Edgar appeared with Johnny at Woodstock in 1969, let alone that he also was an albino and had a jazz-based background much broader than his brother’s slide guitar-based blues and rock repertoire. Edgar’s recently released the 16-cut homage, Brother Johnny, gives you cause to wonder.

Edgar Holland Winter sings and plays keyboards, guitar, saxophone and percussion. He is best known for his hits “Frankenstein” – featuring the ARP 2600 synthesizer where he created one of the most outlandish sounds of the ’70s – and “Free Ride” that he recorded with his band, The Edgar Winter Group. He’s released several albums in half a century that demonstrate a broader jazz-influenced style than his more famous brother.

“I consciously wanted to stay out of Johnny’s way, but we did have different musical tastes,” Edgar told me in 2019. “When we were kids, Johnny had the dream. He had the ambition. He read all the magazines and he watched Bandstand. He had this huge record collection and was Johnny Cool Daddy with the pompadour, the shades, the girls, and the guitar. I was the quiet kid that played all the instruments. I had a deep love of music, but I was very personal, very introverted. I was the weird kid that played all the instruments.”

Would Edgar Winter have had as big or bigger an influence on the history of progressive rock music in the last half century that his brother had if he, Edgar, had the same drive to be a star that Johnny did? In the process of creating this stellar homage, Edgar proves categorically that his muse was – and is – as artistically valid and vibrant as his brother’s entire catalog of releases.

Before he made Brother Johnny, Edgar told me, “Johnny has always been my all-time musical hero and as anybody knows, he passed away in 2014, and he may have departed this physical plane, but his spirit, his music and his presence will live on in my heart forever. He was a true bluesman. He played the music. He lived the life, and he came in and went out the same way: truth to the blues, and I love him for that, and I first want to make this record to honor the music that he played.”

Four months after his brother’s death in 2014, he wasn’t so sure he could do Johnny justice on record. “I had been approached after John’s death, and it just seemed to smack of exploitation. To try to exploit Johnny’s memory and name just to sell records was not something that I wanted to do, and I just felt, ‘Well, somebody is going to do it, but it’s not going to be me.’”

I told Edgar I thought the way he and his brother related to the world was so representative of what’s beautiful about the blues and the fact that both of them were albino. It’s almost as if they understood what it must be like to be black and to be rejected by some people. They must have gone through some hard times when they were growing up.

“Absolutely. I’ve often thought the same thing you’re expressing. I would sneak into those tent revivals. If you think rock and roll has energy, it pales in comparison to that Pentecostal gospel music. We’d sneak into one of those tent things. We’d be the only white people there, and no one ever bothered us. It was a beautiful thing.

“The black club (in Beaumont, Texas where we grew up) was The Raven, and that’s where we’d go see B.B. King and Bobby Blue Bland, Ray Charles and all those people that would come in. The black radio station was KJET, and that was like right down the street from my grandmother’s house. Every Thursday we’d go over to my grandmother’s house for fried chicken, and we’d walk down to KJET. We’d go over there and play on the radio sometimes ’cause the deejay would play some records. Then, he’d pick up his guitar and he’d sing a few songs. We’d go in here and that was always a lot of fun.

“There was a dance club called the Tahiti that we used to play. It was a white club, and occasionally they had this black band that would play there called Big Sambo and the House Breakers. I was there one night. I wanted to sit in with them, and the club owner said, ‘No, you can’t. That’s not acceptable. We can’t.’ I said, ‘What? You got a black band playing for white people, but a white guy can’t sit in with the black band? Why?’

“The whole thing made absolutely no sense to me, and then I also remember one of the bands I had – I had a lot of black friends, and we decided to hire a black singer. His name was Junior Coal, and he used to play a lot of church things, and after I hired this guy, they quit asking him to play.”

I asked Edgar in 2019 to pick out one cut from the then scheduled CD Brother Johnny that takes him back to his childhood with Johnny. “(Long pause) I think probably the most emotional song for me is gonna be ‘Drown in My Own Tears.’ I feel like – uh – I can be singing that to Johnny. It’s a song we did – I did in a lot of his bands, and he did as well. Besides when he said he wanted to do it on the first record, but it doesn’t have any guitar on it. It was like him saying, ‘We’re doing all this stuff that is more country blues, and I know how much you love Ray Charles,’ and I sort of felt he was doing that song for me, you know, to give me a chance to play, to arrange the horns and play piano on it.”

Edgar is center stage in “Drown in My Own Tears” with no guest “stars.” Just before releasing Brother Johnny, Edgar told me, “I felt he (Johnny) was there when I was doing ‘Drown in My Own Tears.’ I broke down several times and cried, but I was so touched when Johnny did that song originally. I wanted to sing that song back to him in the same way he had done it for me so many years ago when he was so alive.”

Brother Johnny consists of 16 songs from Johnny’s half century career and one Edgar original. Each features Edgar playing keyboards, guitar and/or singing with guest artists from a cross section of the rock and pop pantheon.

“I didn’t want to do a nostalgia album,” explains Edgar today. “I could easily have gone around to a lot of the people Johnny played with over the years and done sort of a nostalgia reunion album, and I could have done a straight blues album, but I think if I had done that, I don’t think Johnny would have liked that. I think he would have said, ‘Hey, all of a sudden, you’re adopting my exact style and trying to copy my exact music. That’s not you!’”

Yes, Brother Johnny is an homage and, yes, the songs chosen are all numbers that Johnny recorded and performed in concert, but – and this is a significant but – this is not a record label’s attempt to cash in on that catalog. It is not a greatest hits rehash. In fact, Johnny’s most successful partner in crime Rick Derringer doesn’t appear on the album. Rather, Edgar himself sings on both “Rock and Roll Hoochie Koo” and “Alive and Well,” the two songs most associated with Johnny’s work with Derringer.

Steve Lukather, best known for his work with Toto, plays guitar on “Rock ‘n’ Roll Hoochie Koo,” and Kenny Wayne Shepherd plays guitar on “Alive and Well.” Rick Derringer was the original guitarist on both, and it was with Rick that Johnny enjoyed his greatest commercial success. Unfortunately, Covid prevented Edgar and Derringer from getting together.

Other guests include everyone from Billy Gibbons to Keb’ Mo’. None of them sounds like they’re there for name recognition. They are not trying to emulate Johnny’s techniques, but rather take the songs Johnny was best known for as a jumping off point for their own contributions.

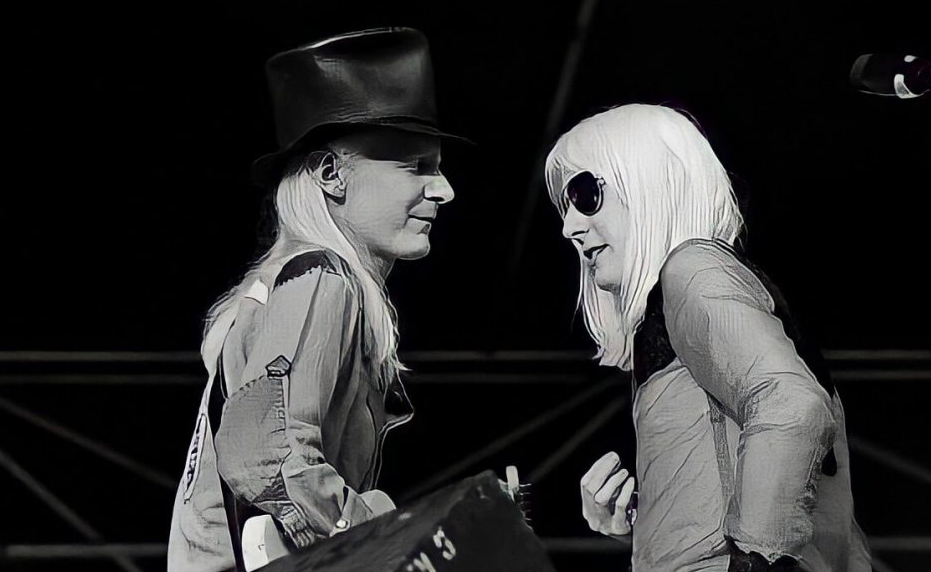

On Brother Johnny, Edgar reprises “Mean Town Blues,” a song his brother delivered to half a million fans at Woodstock. Edgar sings it with an almost vicious tone, and Joe Bonamassa plays slide guitar. Edgar recalls that day in 1969 at Woodstock. “I think he’d already done “Mean Town.” I wasn’t on stage at that moment. Johnny would do the first part of the set with this blues trio, and then he would say, ‘And now, I’m going to bring on my brother Edgar.’”

“I’m Yours And I’m Hers” was the first track off Johnny’s 1969 LP titled just Johnny Winter, a defining marker in establishing Johnny as a slide guitar juggernaut. Fittingly, Billy Gibbons and Derek Trucks take this one on.

“Lone Star Shootout” is probably the most startling example on Brother Johnny of Edgar giving the guest artists carte blanche. Keb’ Mo’ shares lead vocals with Edgar and plays all guitars and bass, and the result is very down home.

“Got My Mojo Workin’” features Bobby Rush on lead vocal and harmonica with Edgar playing piano. “He started to play that song, and I went, ‘Oh, this is the real deal. This is it.’ When he started singing ‘Mojo’ and playing I couldn’t believe this guy is in his 80s. It was really special when he did this song.”

Edgar wrote “End of The Line,” the only new original on Brother Johnny.

“When I got the idea for the title, I said, ‘End of the Line.’ That’ll be the last song I’m doing. and I started to write it. I became aware, oh, it’s the end of the line. I’m writing about our family. I’m writing about the Winter lives. Johnny and I are the last remaining Winters. Now that he is gone, I am the last of the Winter line. So, it’s a very emotional song.”

Brother Johnny is an homage, but Edgar so redefines his brother’s signature songs, one has to wonder how he might have equaled or even surpassed Johnny’s fame, had he possessed the same obsession for success.