The high-energy, close-harmony sounds of bluegrass can be dated back to the ‘30s. And the genre’s name is derived from mandolinist Bill Monroe’s band, The Blue Grass Boys. Having been a guitarist and vocalist in that band alongside the father of the high, lonesome sound at a time when the folk music revival was at its peak, it’s safe to say that Peter Rowan is a living history of bluegrass.

By weaving a panoply of textures with bluegrass – newgrass, Americana, country rock, jazz, Hawaiian, Tejano music, and even reggae – he’s ushered in a style all his own while preserving the handcrafted art. “Bluegrass accepted me first as a cultural pilgrim,” Rowan explains. “I’m still the pilgrim, interpreting my experience through music. And the richness is the collaboration with people from really any culture. Musicians are transcultural, you know.”

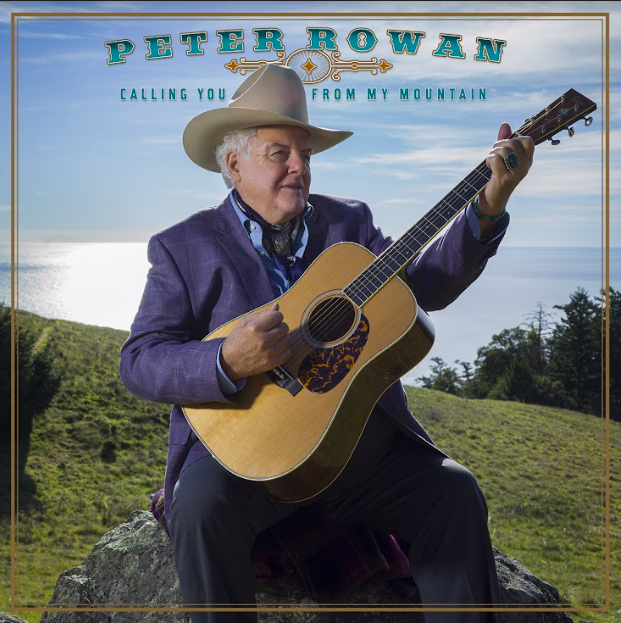

He reflects on the potential that Monroe saw in him as a budding artist, “I think as a man in his 50s looking at a 22 year old kid, he saw me. He saw who I was before I did. He’d always yell at me on stage ‘Sing it like Pete Rowan!’ He always wanted the individuality to come out.” Just like Monroe, Rowan has enjoyed 60 plus years as a cutting edge musical influence. At 79 years old with no signs of slowing down, he is now assuming his mentor’s former job on his latest effort. Calling You From My Mountain, out June 24, 2022 on Rebel Records, features roots musicians Molly Tuttle, Billy Strings, Shawn Camp, Lindsay Lou, and Mark Howard.

Rowan’s own band includes Chris Henry on mandolin, Max Wareham on banjo, Julian Pinelli on fiddle, and Eric Thorin on acoustic bass. Of his multi-generational band, he enthuses, “They’re bursting with ideas. They’re in their years of inspiration. They’re really quick learners and their ears are wide open because this generation is built on everything we did, dare I say, all those years ago.”

The inspiration for Calling You From My Mountain came from the simplest, most honest of sources: his favorite Hank Williams LP. “When I left Nashville in 1990,” Rowan says, “the only country music album I had, besides one Ernest Tubb record, was Hank Williams Sings Luke the Drifter. So, I listened to that all the time on my little turntable, and I just loved that Hank had an alternate ego who was himself but the sentimental-songs-with-a-message side.”

Before Rowan could travel to Nashville to record the album of songs influenced by Luke the Drifter, the pandemic had a different plan in mind. So he stayed home, gazing across the California coastal landscape and canyons. With old songs bringing forth ideas for new ones, he managed to keep ol’ Hank’s spirit alive by including the song “Dream of Heaven.” He says, “By doing that, I started to find my own voice again as to what I really wanted to say on this record.” The companion song is “The Red, the White and the Blue,” which Rowan says is like a Carter Family approach with Molly Tuttle singing the harmony and playing banjo and Shawn Camp on guitar.

Other interests and connections find Rowan on Calling You From My Mountain, whether it’s Tibetan music and his Buddhist beliefs and practices, or his love for folks like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Guy Clark, Bill Monroe, and Tex Logan – all of whom Rowan’s played and performed with. As a lifelong fan of the blues, Rowan has spoken at length about how the genre played an instrumental role in Bill Monroe’s original creation of bluegrass.

He has toured with Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee and even tracked down Lightnin’ Hopkins once, stating in his liner notes: “Lightnin’ Hopkins’ ‘Penitentiary Blues’ was a revelation to me. I heard it while I was still playing record-hops as a kid around Boston with my band, The Cupids. Lightnin’ led me to Leadbelly, Huddie Ledbetter, whose song ‘Black Girl’ led me to Bill Monroe singing ‘In the Pines,’ and thus to the heart of Bluegrass.”

Today sees the exclusive premiere of Peter Rowan’s bluegrass rendering of “Penitentiary Blues (Big Brazos),” written by Blind Lemon Jefferon and covered by Lightnin’ Hopkins.

Rowan tells ABS:

Lightnin’ Hopkins traveled with Blind Lemon Jefferson, soaking up the master’s touch for the blues. They traveled all over east Texas and Oklahoma. “Don’t call him no blind man, nossir,” said Lightnin’.

This is the first song by Sam Lightnin’ Hopkins that I heard in 1958, and It changed everything about music for me. I’m so glad to finally be able to sing it here. It makes a fine bluegrass number!