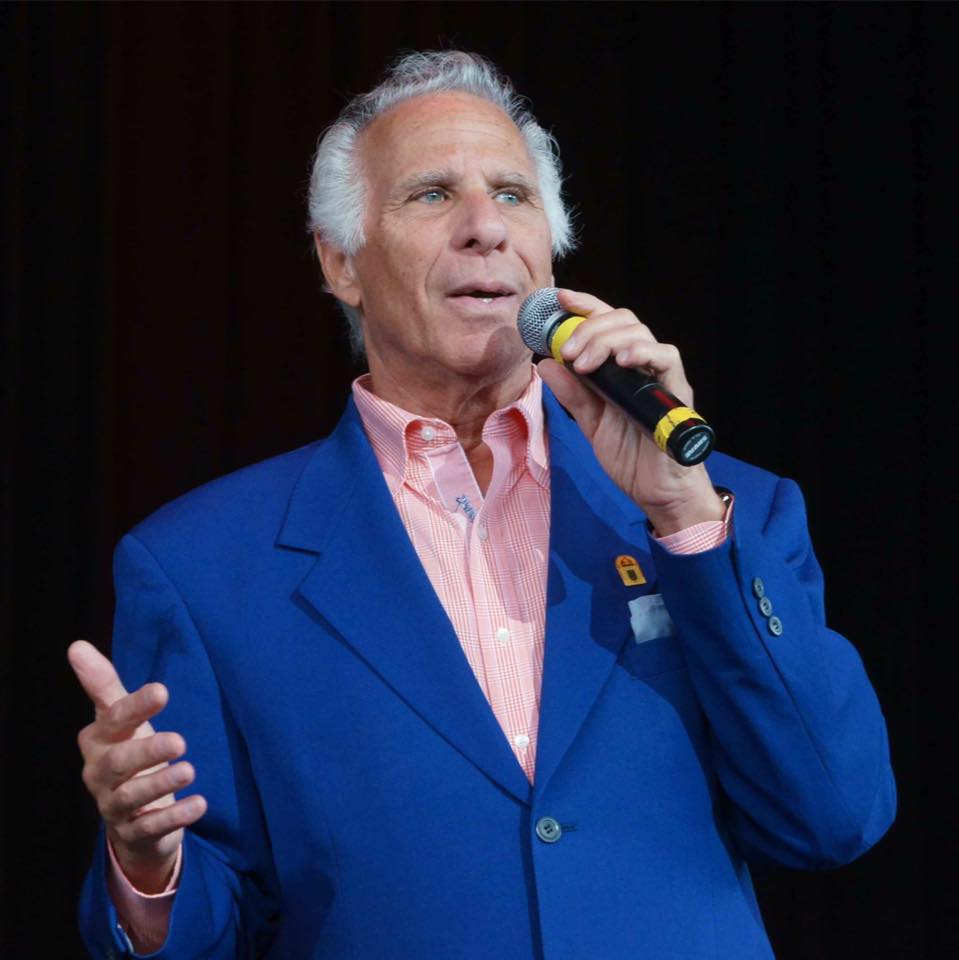

“In the jungle, the mighty jungle, the lion sleeps tonight.” Twenty-four hundred people sang the line in unison with Jay Siegel of The Tokens at The Golden Oldies Spectacular in Schenectady, New York the day before May Day, 2022. Most in the audience were in their 70s. They knew to words to “The Lion Sleeps Tonight’ as surely as they did “Mustang Sally” covered by the Brooklyn Bridge, or “Higher and Higher” belted out by soul master Jackie Wilson’s son Bobby Brooks Wilson. Or Buddy Holly’s “Everyday” sung by Vito Picone of the Elegants.

Jay Siegel has built a half-century career around “The Lion Sleeps Tonight,” the distinctive number his band The Tokens took to number one on the Billboard Top 40 chart in 1961. Still performing the song today at age 83, Siegel’s email features a photo of an imposing lion in repose. But few people know that the heritage of that song with its high falsetto “Wimoweh” scat has a history that dates back to the gospel jubilees of the 19th century.

It first made the charts in 1939 by a South African singer named Solomon Linda. It has been covered by everyone from Pete Seeger and The Weavers, Miriam Makeba, R.E.M., Brian Eno, The Kingston Trio, Glen Campbell, and the Spinners to name a few, and was featured in the 1994 Walt Disney film The Lion King where it is sung by Timon the meerkat (Nathan Lane) and Pumba the warthog (Ernie Sabella).

“My son just took his two kids to Disney World for vacation,” says Siegel today. “They went into The Animal Kingdom, and what record do they play? They’re playing my record. That’s a lot of years later. RCA put ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’ out. They released it, and within four weeks it became number one in the country, stayed on the charts for about three months. Then it sold about three million records in the United States, was released all over the world and became a number one record in 36 countries all over the world.”

Rolling Stone called it the most famous melody ever to emerge from Africa, stating in 2000 there were around 160 recordings of three versions, 13 movies, half a dozen TV commercials, a hit play, and “ceaseless radio airplay in every corner of the planet.”

A sleeping giant, it has awakened anew every few years for more than 80 years across cultures and defying genres. Each iteration puts a twist on a song that owes its genesis to the primal calls of the African jungle.

It’s the song that would not die.

Solomon Linda is said to have been inspired by the celebrated Virginia Jubilee Singers, a 19th century combo that specialized in syncopated spirituals. Standing almost seven feet tall, Linda recorded “Mbube,” in the only recording studio in black Africa with his group Evening Birds wearing pinstriped suits, bowler hats and dandy two-tone shoes. He sang soprano, what Zulus called fasi pathi, a blood-curdling falsetto.

Rolling Stone described the song as “a simple three-chord ditty with lyrics something along the lines of, ‘Lion! Ha! You’re a lion!’ inspired by an incident in the Evening Birds’ collective Zulu boyhood when they chased lions that were stalking their father’s cattle. The third take was the great one, but it achieved immortality only in its dying seconds, when Solly took a deep breath, opened his mouth and improvised the melody that the world now associates with these words: ‘In the jungle, the mighty jungle, the lion sleeps tonight.’”

By 1948, “Mbube” had sold in the region of 100,000 copies, and Solomon Linda was the undefeated and undefeatable champion of hostel singing competitions and a superstar in the world of Zulu migrants.

Jay Siegel first heard the song by the folk purists The Weavers, best known today for their first recording “Goodnight Irene” done originally by Lead Belly.

“So, one day we came in and sang – it was not ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight.’ It was a song I heard on the radio taken from an album called The Weavers in Carnegie Hall, the biggest vocal group of the ’50s.”

Pete Seeger was one of the members of The Weavers. “I met Pete once. We did an outdoor series in Chicago. I met him in the lobby and said, ‘If it weren’t for you, I wouldn’t be here.’ And he knew who I was of course. He knew about the record.

“We sang ‘Wimoweh,’ the song I heard from the Weavers, and they (producers) Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore) said, ‘That record sounds like an interesting melody, but I think it should have some kind of lyric because we just can’t do a falsetto thing with a chant in the background.’

The Tokens were formed in Brooklyn by high school buddies in the 1950s. By 1961 they’d had one hit “Tonight I Fell in Love,” for an indie, Warwick Records. “We never got paid, and that record was number one in most of the areas of New York or the Tri-State area. It was number 15 on the national charts, and one day we went to the President’s office and said, ‘We have an offer to come with RCA, you know, Elvis Presley and Perry Como, all those great artists.’ So, the four of us said, we’re leaving and going with RCA Victor, and the president of Warwick said, ‘I just gave you a big hit record. What did this do for you that I can’t do for you?’ And we all in unison unrehearsed said, ‘Pay us!’ And we walked out.

“So, we went to RCA and were assigned to Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore who were very hot record producers from Sam Cooke to Perry Como to all the major artists at RCA, and we had a bunch of records, three or four singles that came out that hit the national charts that (cover) the top 40 records.”

“I feel very good about this because, yeah, we had a lot of success. Producing records for other artists because we didn’t know after “Tonight I Fell in Love” if really maybe we’d be one-hit wonders.

“So, we were gonna learn about the music business. We were the first vocal group to produce a number one record for another vocal group, and that first record we produced was He’s So Fine by The Chiffons, and we did produce all their records plus all The Happenings records, and Randy and The Rainbows’ record Denise, and all of Tony Orlando’s first three records: Candida, Knock Three Times, Tie A Yellow Ribbon. So, we were in the studio all the time producing records for other people as well as ourselves.”

Still, The Weavers’ version of “Wimoweh” stuck in Siegel’s head.

“I found it was an African lullaby. When the tribe would go out on a lion hunt, they would do this beautiful chant and sing this falsetto melody. The lion would be sleeping, and they would be able to make their kill, and then they would have lion meat for the next three months for their village. That was what the song was about. They (at RCA) had a partner they worked with. His name was George Wiess and George Wiess wrote some big hit records, Can’t Help Falling in Love and What A Wonderful World, and he came up with the big 10 words: ‘In the jungle, the mighty jungle, the lion sleeps tonight.’

“So, I walked into the studio. Our contract was supposed to be over at RCA. We walked into the studio, and I was given this yellow legal pad with the lyric, and I said, ‘What a record! This lyric I can’t fit into the melody I’m familiar with. There’s too many words.’ I had to come into the studio with a melody that would fit into the lyric. So, I actually co-wrote half of that melody which Georg Weiss and Hugo and Luigi took credit for writing the music which they had zero to do with, but they took the credit, and they made a lot of money, So, that’s the real story.

“So, we made the record. Luigi called in an opera singer from the New York Metropolitan Opera, Anita Darien. Then, we had one of the instruments in the rhythm section is a bongo, and then we have a soprano saxophone that sounds like Guy Lombardo. This is the weirdest record I’ve ever heard, and three of the guys in the group did not want this record to be out. Why? Because who is going to play this record? There’s nothing like this record. It goes against everything in the market. So, I responded to the three guys. ‘Maybe that’s the reason it should be released because there’s nothing like it.’

They said, ‘Oh, I don’t think anything’s going to happen with this record.'”

RCA put it out and it shot to the top of the charts. In 1962 Miriam Makeba sang her version at JFK’s last birthday party, moments before Marilyn Monroe famously lisped, “Happy Birthday, Mister President.” Apollo astronauts listened to it on the takeoff pads at Cape Canaveral.

“If you tell anybody from the ages of two years old to sing ‘The Twist’ (which bumped ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’ off number one in 1961) or ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight,’ they’ll all come up with ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight.’ There’s still nothing like it, and they tell me to this day somewhere in the world this record is being played every day.”

In Schenectady, Siegel had a bad case of laryngitis, and he had the audience sing the “in the jungle, the mighty jungle, the lion sleeps tonight,” but when he came to the falsetto “awimoweh,” he took that crowd through the roof, nailing it perfectly.

Before the show he told me, “I’ve been doing this my whole life. In my mindset (every time I go on stage) is the first time I’m singing these songs. I want to do it just like the record, and I want those people to walk out with a big smile and be really happy.

“There are a lot of acts that say, ok, another gig. Take the money and run. I feel so honored that people are still coming out and supporting me and supporting my music that I don’t take it for granted at all, and the answer is absolutely not. I’m going out there, and this is the first time, and I still want to be the best I can.”

“The Lion Sleeps Tonight” cuts across cultures and genres and inspired scores of artists who have built their reputation on singing music that changes the way we look at the world.