In 1969, The Edward Hawkins Singers broke into the pop charts with “Oh Happy Day.” It was black gospel, pure and simple. For some reason known only to God, it rose to number 4 on the pop charts and went in regular rotation on AFVN (Armed Forces Vietnam Network), a ray of sunshine in the monsoon that permeated the horror for grunts in the rice paddies of Vietnam.

Producer Bruce Watson just may be the producer to make such an anomaly happen again in an America that’s becoming as dangerous as Vietnam was in 1969. “I just try and do what I love, you know, regardless of where it takes me, but it seems the more edgy stuff is always the stuff (I’m drawn to).”

Watson was the producer of Whatever You Need, an album by sacred soul singer Johnny Ray Daniels whom I interviewed for American Blues Scene in early May. A 30-year veteran producer with a myriad of albums to his credit including music by everyone from Al Green, CeDell Davis, Jimbo Mathus, and Super Chikan to Jimbo Mathus and T-Model Ford.

He’s currently CEO of Bible and Tire Records out of Memphis. “We’ve never really looked for mass acceptance. You know, it’s like I started this label just because I’ve lived in Memphis for almost 30 years, and I was kind of looking around for what the landscape of Memphis was.

“It seemed like there was a lot of garage rock, a lot of neo-soul, plenty of hip hop going on in Memphis. But the really edgy, raw gospel stuff that still happens in some of the small churches really wasn’t being documented. So, that’s how I got into it.

“As far as mass acceptance, I don’t kid myself. Soul gospel, or sacred soul as we like to call it, is just a hard sell. And most of the artists I work with are 70 or 80 years old.”

Watson records these artists usually backed by a studio band. Together, these lifelong veterans of the Southern Baptist Church backed by young musicians who also earned their chops in church take these recordings to a heaven rarely heard in most modern recordings.

“I just try to make my money back; I’m happy. I know that’s a horrible business (plan) but at this point in my career I just want to follow my muse and just do what I really enjoy, and this is what I really enjoy right now.”

“It’s soul music without the sex,” he told NPR about his Bible and Tire label. In a way, he’s a modern-day Barry Gordy. On Motown Records, Gordy made black pop music for white audiences. Watson’s doing the same thing with gospel. He calls it sacred soul.

“Totally, that’s what I’m doing. It’s kinda like the same thing with the blues. (At Fat Possum Records) we were trying to get the blues like R. L. Burnside and Jr. Kimbrough into the rock clubs with young white kids. There is small contingency of white kids who slide into this. It’s black gospel, but sacred soul.

“I’m almost 60, and I’ve been doing this for 30-plus years. At this point, I just want to have a legacy of stuff I’m really passionate about, and that’s why – I’m not getting rich. In fact, I’m losing money doing it. I mean it’s not that bad. It means the world to a lot of these older artists who’ve been overlooked for years to be able to put something out.

“I don’t consider myself religious, but I do consider myself spiritual in a way. The blues and gospel are all kinda the same thing. It’s just the balance of the sacred and profane. I’ve always been attracted to that, you know?

“We’ve been putting out raw blues records for 30 years, and we had a little bit of success with R. L. Burnside, but most of the records we made with blues guys never really went anywhere. R. L. Burnside and Jr. Kimbrough to a lesser degree were the two successful ones, but we put out probably 100 other blues records that weren’t successful at all.”

The biggest quake by the relatively new Blues and Tire Record label so far came with the release of Sacred Soul of North Carolina that earned acclaim from NPR Music, MOJO, DownBeat, and noted music critic Robert Christgau who named it his number 20 album of 2021.

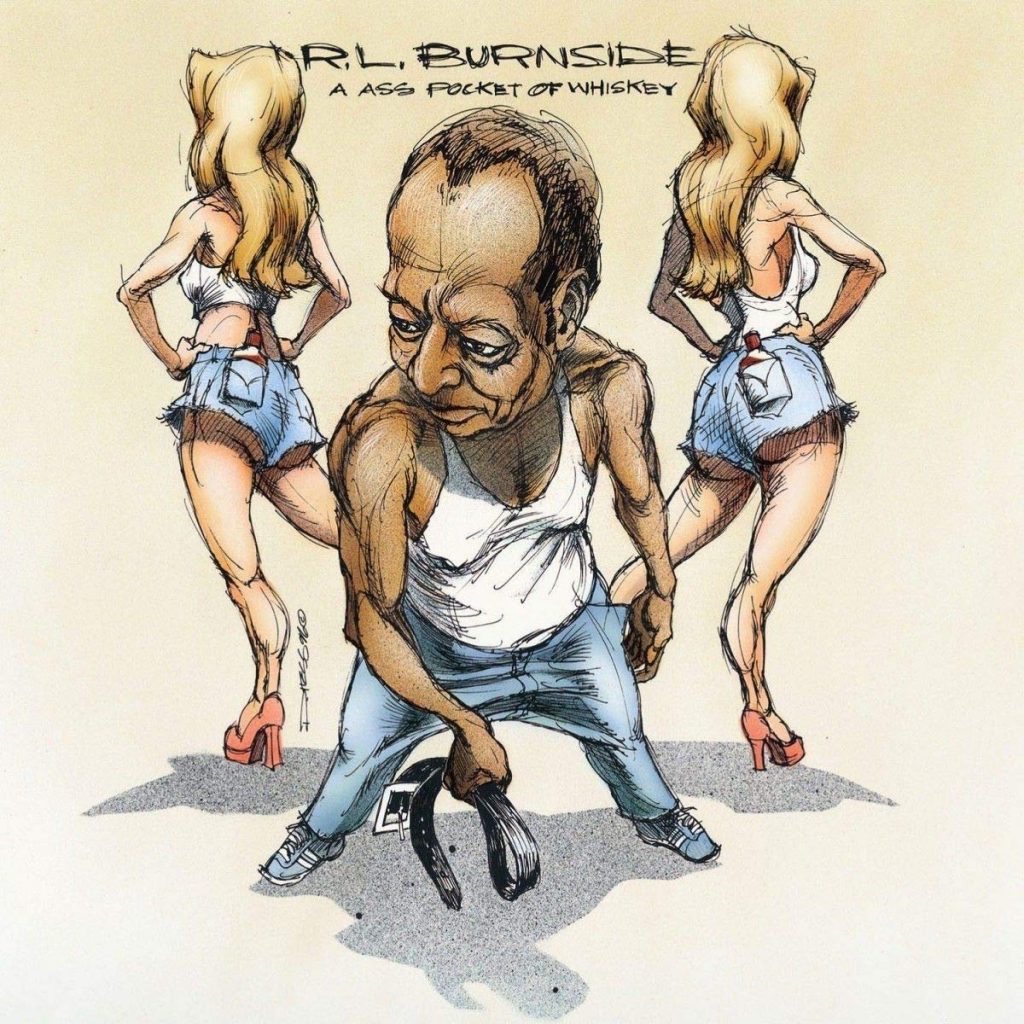

Some of Watson’s early work with Fat Possum Records was with R. L. Burnside and the Jon Spencer Explosion. A Ass Pocket of Whiskey sold more than a quarter million copies worldwide.

With tongue half in cheek, I asked Watson if he’s seriously insane or simply addicted to what he does. “I think I’m both.”

The song “Lord Hold My Hand” (ABS premiere) on The Dedicated Men of Zion’s The Devil Don’t Like It album is all I need to prove this guy is a gift to anyone who loves music, regardless of the genre. “Yeah, yeah. That’s a great song. It’s been eight months since I did that record. I can’t remember who the original artist was. They learned the song and just tore it up. That was so good, man. That record is really strong.

“That’s the second record I’ve done with them. Basically, it’s the quartet backed by my studio band. The Sacred Soul Soul Section. But they’re young. They’re all between 25 and 30 years old. They’re younger guys. They have a tour coming up. So, they’re really fantastic.

“When I first started listening to sacred sound music, it moved me the same way as hearing R. L, Burnside or Jr. Kimbrough the first time I went out to a juke joint. There’s a lot of the same emotions. You’re talking about God instead of talking about screwing a whore or drinking moonshine, or this and that. It’s all human emotions. You gotta view that the same way.”

Watson is the latest example of producers and label heads who record what they do simply to expose the artists they love to a wider audience for altruistic reasons. If these musicians sell enough records to make money, all the better, but that’s not their reason for releasing “product.”

My friend Bill Nowlin fronted Rounder Records for half a century releasing more than 3500 albums by artists who mostly lost money. George Thorogood and Alison Krauss with Robert Plant made Bill and his partners millionaires, but they were anomalies. Bob Koester founded Delmark Records in 1953 to record South and West Side blues artists as they sounded in the clubs, not as studio productions. Little Village Records is a not-for-profit label creating recordings with the artists first in mind.