The death of Rolling Stones’ drummer Charlie Watts, in all sincerity, played like something out of a movie. At least that’s what it felt like to me. I listen to music (loudly) in the shower, and as I get out I often pick up my phone to change the song. But instead of switching tracks, this time I am suddenly dispirited by a breaking news notification on my lock screen with the cold, cruel words: “Rolling Stones Drummer Charlie Watts Dies at 80.” My jaw and phone drop reflexively just as the opening strains to Greg Graffin’s somber piano ballad “Cease” swell and fill the room.

It’s possible that Greg Graffin — who holds a Ph.D in zoology and a master’s in geology, lectures courses in natural sciences, and has three published books centered on evolutionary biology — wrote the poignant words and music to broadly address the natural world in all its unnatural conditions. However, “Grave memorial, hewn white stone / Like the comforting caress of a mother or a friend you’ve always known / It evokes such pain and significance / What was once is reduced to remembrance / And the generations pass without recompense / What pretension, everlasting peace / Everything must cease.” What was Watts if not the caress of the band and the friend we’ve always known? Always there, since 1963, in fact — having played on all their studio albums and never missing a gig — and the backbeat to quite literally my entire life.

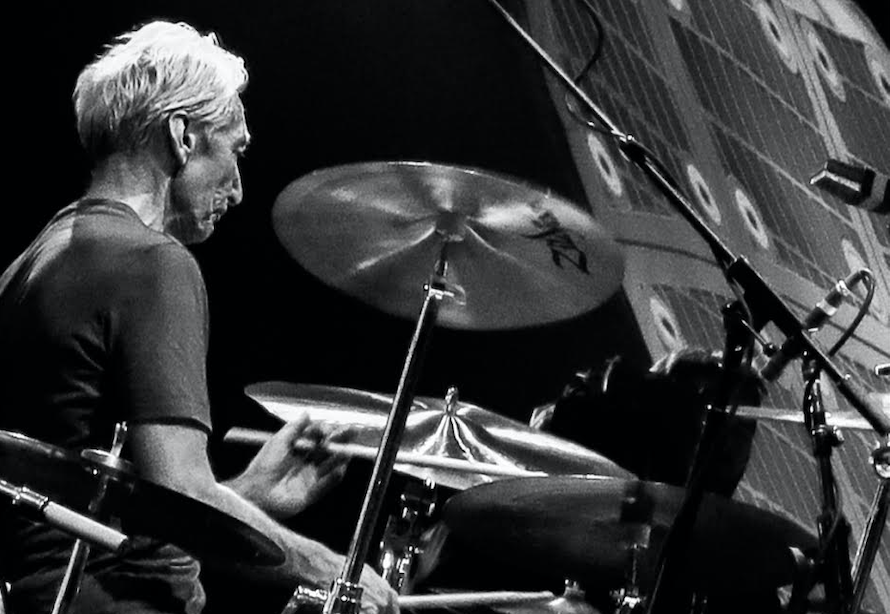

The heartbeat of rock and roll. The engine of the Rolling Stones. Best in-the-pocket drummer of all time. These words are not superlatives! His background in jazz taught him it’s not always what you play, but what you don’t. In his first mention of playing with Charlie, Keith Richards shares in his autobiography, Life, an early diary entry: “Charlie swings but hasn’t got right sound yet. Rectify that tomorrow!” He then goes on to instead rectify his statement: “Charlie Watts has always been the bed that I lie on musically, and to see that note about how to ‘rectify’ seems extraordinary.”

It’s been said that music is the space between the notes. I believe Charlie dedicated himself to the art of subtlety far beyond efficient use of the hi-hat, and made the Stones the Stones. For the weeks following his death, rollingstones.com had no links, but an image of Charlie Watts in a beautiful bespoke suit took up the whole page. A fitting tribute. And now, they’ve since painted their 50-year-old Hot Lips logo from red to black to honor their fallen friend. As if to say, indeed, it does mark the end of an era.

From rock and roll’s primordial soup, I won’t try and narrow down or rank any combination of songs. But I would like to remember Charlie through the lens of some of my favorite Stones moments.

I’ve wondered many times if December’s Children is my favorite Stones album, not to be generally well-received when spoken out loud. Indeed, Mick and Keith wrote only half the songs, but the album features such fundamental, harmonizing originals as “The Singer Not The Song” and “Blue Turns To Grey.” I like to think that December’s Children was something of a proto-punk blueprint, Alex Chilton later cutting his version of “The Singer Not The Song.” The Stones’ rendering of Muddy Waters’ “Look What You’ve Done” was my wide-eyed introduction to the grace and gusto of blues harp. “Get Off Of My Cloud,” released as a single in 1965 and included on December’s Children that year, is a foremost example of Charlie’s iconic snare fills. The drum pattern is repeated many times throughout, and not one time does it get old. Rather, it makes the song.

“Mother’s Little Helper,” played in a minor key, kicks off the UK edition of Aftermath in a major way. Brian Jones’ Rickenbacker played with a metal slide may be its most salient feature, but the rhythm section is the stimulating and steady undercurrent driving the train. As Bill Wyman’s bass parts with glissandos lend to the dark, writhing quality of the two electric 12-strings, Charlie Watts propels the downbeat and comes on like thunder. Charlie himself noted in the 2003 book According to the Rolling Stones that they could never quite recreate “Mother’s Little Helper” up to their standards — though they did try a few times, including on The Ed Sullivan Show.

Sandwiched between lead single “Brown Sugar” and molecule-changing ballad “Wild Horses,” how could “Sway,” a deep cut about demonic depression, be the cornerstone of Sticky Fingers? Besides that it’s arguably Mick Taylor’s finest lead work? As with most Stones songs, Charlie enters with an understated momentum and staying power that takes the song where it needs to go.

“Doo Doo Doo Doo Doo (Heartbreaker)” tells a tragic tandem tale of ten-year-olds: one boy shot through the heart by police “in a case of mistaken identity” and one girl who died of an overdose in an alleyway. The raw power of Billy Preston’s clavinet intro brilliantly played though a wah-wah pedal, Mick Taylor’s phrasing and effects, and Bobby Keys’ sweeping sax mirror the fury and heartbreak of the inner city. What makes this rock and roller stand out, anomalously, is the simultaneous muscle and light, nimble touch of the man behind the Gretsch kit.

From Mick Jagger’s back-of-the-cab vantage point, “Shattered” is another indictment of ‘70s NYC street life. Jagger uses the Yiddish word for rags, schmatta, also a byword for the golden age of the Garment District of which Jewish immigrants were the fabric. Peppered throughout the song are handclaps, a decisive snare roll, tom fills, and other signature Charlie moves making for one of those total package Rolling Stones songs.

One year ago today we lost Charlie Watts. In the words of Mick: