Willie Dixon was the unsung father of Chicago blues. Artists like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, Koko Taylor, Bo DIddley and Otis Rush were making waves during the 1950s. But the man behind the scenes with the bass and the song repertoire was Willie Dixon, a staff writer and producer at Chess for many influential years. But Dixon had a past worth mentioning: A Golden Gloves boxing champion, segueing into being one third of the jump-blues Big Three Trio. From there to Chicago, he wrote the songs that made the Chess stars into global hitmakers. Dixon was on salary, and his publishing was owned by Arc Music. But later, Dixon took control with his own label, management company and of course publishing company.

Among his hundreds of classic songs: “Hoochie Coochie Man,” “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” “Little Red Rooster,” “I’m Ready,” “My Babe,” “I Can’t Quit You Baby,” “You Shook Me,” “Evil,” “Spoonful,” “The Seventh Son,” “Wang Dang Doodle,” and “You Can’t Judge a Book by the Cover,” to name but few.

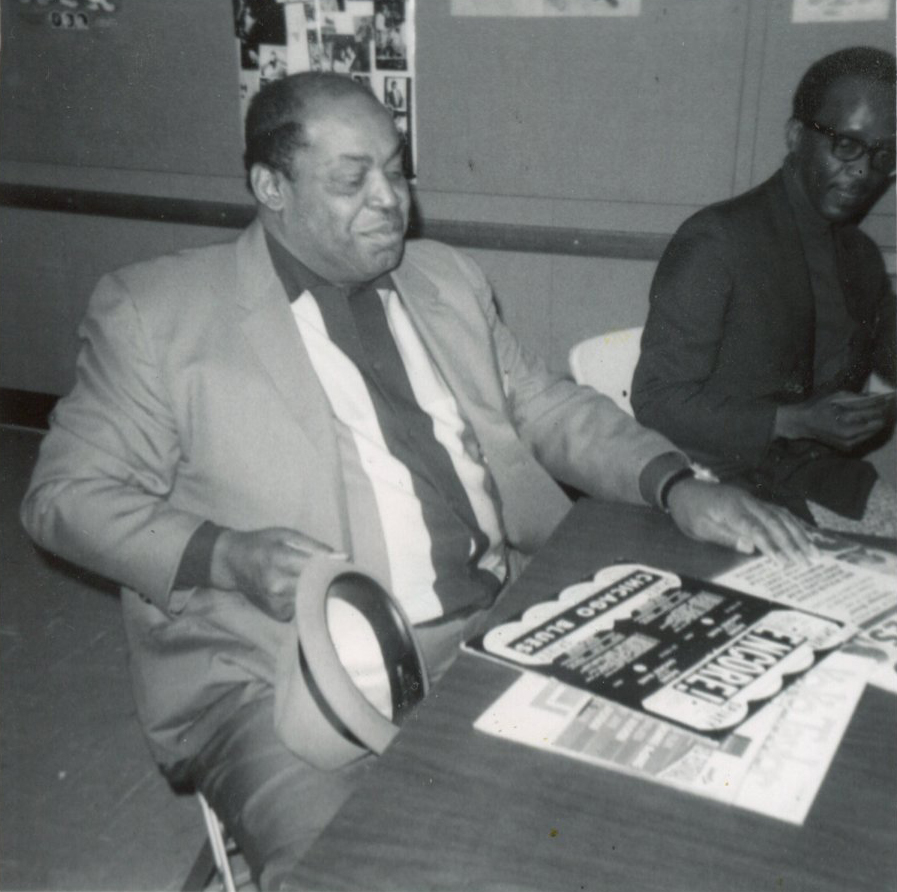

I met Willie on many occasions — the first of which is when I cold-called him out of the Chicago phone book and asked him to come to my high school radio station, WNTH-FM in Winnetka, Ill. He obliged and couldn’t have been more gracious. This was followed by an invitation for me to visit his studio at 7711 S. Racine Ave., in Chicago’s South Side, and I jumped at the chance. This interview was conducted there in 1971. I was 16 years old but was a diligent student of blues.

Here’s how our conversation unfolded…

CB: Suppose we start by talking a little about the Blues Heaven Foundation you’ve formed.

WD: The Blues Heaven Foundation is an organization I’ve been intending to start for over 30 years. But I was financially short, and had nobody to work with and nobody would work with me. Now, knowing that you know as well as I know that over the years that blues musicians have been branded as drunks, inferior people who didn’t give a doggone or just some guy who’s sittin’ around cryin’ the blues about everything. But I have known all my life that it wasn’t just that. The things the people see in front isn’t the story all the time. It all comes from the facts of life, and the facts of life can exist from the beginning until the end. And this is what the blues is all about — to explain the various facts of life so that other people can understand that their life is the same as yours. And so this Blues Heaven organization that I have just about together now — I figured it would be a good place to let the world know what the blues are. And also, to let the world know what can be done about the blues. Also, it would give a lot of the blues artists various things to get involved in other than hangin’ around in the streets, getting loaded and acting like a nut.

You see, the blues is actually the root of all American music, and a lot of folks don’t know this. The blues is the facts of life. And blues came from the various experiences that people have had in life, all their life, and people decide they’re going to sing about it. If a guy doesn’t have a lot of education to work with, he has to sing it according to the way he feels. And a lot of times, a guy feels different from you but you don’t know it no more than just looking at it, and because if he can’t explain it, he can’t tell you. But I’ve been lucky enough — I don’t know if you’d call it lucky or unlucky — to have had a bit of experience about all of it from my childhood days until the present day. And I know when a man is singing about something, what he’s singing about and the way he feels about it.

If a guy’s singing about goin’ up the country, and I won’t be back no more, and you say, ‘What does he mean he won’t be back no more?’ Well, he means what he says. He was probably in the South or somewhere where he wasn’t getting the proper treatment or the proper understanding, and he feels like he’s downtrodden. And he feels like it’s time to get the heck out of there because he’s tired of this place. There was a fellow that asked me not long ago about, “What do you mean by ‘Blues jumped a rabbit and jumped him for a solid mile?'” Well you see, if the guy had come along with me when I was in the South, there were many days when the dog didn’t jump a rabbit or my old man didn’t shoot a squirrel and we didn’t eat before we went to school.

Then when a guy say ‘Goin’ Down Slow,’ I know many people who could express that better if they could explain it. A fellow having enjoyed the best of his life in many places and then he gets one place where he isn’t having so much fun and says, ‘I’m not going to be here much longer.’ And he started thinkin’ about it and says, ‘Someone write my mama and tell her the shape I’m in and tell her to don’t send no doctor,’ and all these things. All of these are the facts of life. And when the world understands this as the facts of life and quit trying to ridicule people because they think this is just something they made up, then they’d make a better understanding. And a better understanding makes a better world all the way around.

So I feel that if the blues were properly understood, the world would be a better place to live in because the average person that don’t understand the blues can’t realize what a position a person would be in when, in the first place, they took his country. In the next place, his language; the next his religion and they took all of his traditions. And then they forced him into other things that he disapproved of all around. It would be like you being forced to be an Indian or an African or something. You find you’re doing the same thing your foreparents did. They brought them to the States to be a slave and work, and you’re still being a slave and working. The other man supposed to be the boss; he’s still the boss.

So I feel people can be educated with what I call a blues education. This is what the Blues Heaven Foundation is all about. And also to produce grants and to teach people to have different kinds of occupations to help themselves.

CB: You’re applying for grants to achieve this?

WD: I’m definitely trying to get grants to educate the children to various things to help them in the future. It’s also a good thing to educate them to blues and their heritage, learning to play an instrument and the facts of life – – this is why the blues needs an organization. We need to have a better understanding of blues so the world will know blues is the root of American music.

CB: What is the Blues Factory, and how does it relate to your Blues Heaven Foundation?

WD: Frankly, what we use the Blues Factory for is to teach the kids different trades and keep ‘em off the streets. The average kid gets out onto the streets and makes a little fightin’ and raising hell. If they’re here in the Blues Factory, they can learn how to play piano, learn how to bang on the drums, learn how to play on the guitar. They can learn the art of making signs and instruments. These things can help them in lots of ways.

They say, ‘That’s someone’s song and that’s someone’s song.’ Hell, no! I made these songs, and I made them first! They think I’m the copier when I’m the original.

Willie Dixon

CB: What about your own recording activities? I know you were recently in Paragon Recording Studios in Chicago updating a song called “It’s in the News” from your Peace album for Mexican reissue.

WD: Oh yeah. I had to update it, because on February 4-5, I’m going to be in Washington, D.C., at the Smithsonian Institution. They have a regular concert — I played that before. But in this particular concert, it is my intention to get over some of the facts of life about the blues, and also I’m thinking of having a record out there that the President and Congress can use to enlighten themselves a little with this one tune, “It Don’t Make Sense/You Can’t Make Peace.”

CB: What do you think Reagan’s outlook on the blues is?

WD: Well, I don’t know what his outlook is, but I know what everybody else’s outlook has been of the past. Because if the world were wise enough to make all these other great things, they still haven’t been wise enough to make peace. I don’t think this one is going to be any better. But I think if we have a way of getting to ’em and putting a few thoughts in their mind, they might get together and do something else besides fight.

CB: The album originally came out on your own Yambo label. And now it’s going to come out on what label in Mexico?

WD: I think it’ll be out on my label down there. I’m not sure. It’s been on my Yambo label all the time, but I never did push it or anything.

CB: Do you have the Yambo label still?

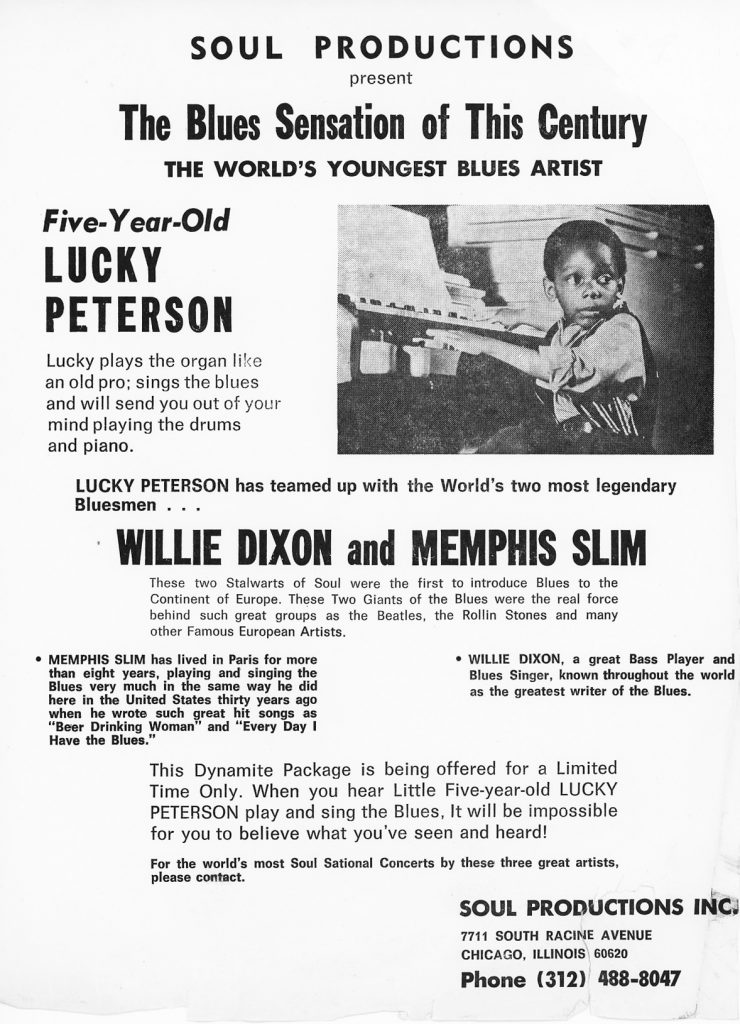

WD: Sure, I still have it, but I haven’t really been using it. The last thing was “The Last Home Run,” by (baseball star) Hank Aaron. You heard that? (Dixon later became more active with Yambo releasing 45s by Lucky Peterson, and an LP by WVON DJ E. Rodney Jones with Lafayette Leake blues trio on Side 2, and more.)

CB: Actually, no hadn’t heard the Hank Aaron.

WD: “The Last Home Run” and “Hank Done It Again.” You know, another thing about Blues Heaven is I think it can wake up a number of people. Through generations, you can reach back to Memphis Minnie, Robert Johnson you can reach back to thousands of them, The kids don’t know nothing about them, but still they were great artists. And many of the songs that came out in the later years they never got a call or any recognition. There have been many people who have dipped in the blues bag to get a rock number, dipped in the blues bag to get a boogie-woogie, or a spiritual or a Dixieland or a Country & Western, They all come out of this one big bag, but the blues never gets the recognition. I go out among the public and people. hear me sing “Hoochie Coochie Man,” “Make Love To You,” “My Babe,” all these different things. They say, ‘That’s someone’s song and that’s someone’s song.’ Hell, no! I made these songs, and I made them first! They think I’m the copier when I’m the original.

CB: Has anyone ever outright taken credit for one of your compositions?

WD: Oh, I’ve had several different people do that kind of thing. I don’t make a big thing of it. But after learning about copyrights and those things, it doesn’t matter whose name is on it. I’ll get the benefits anyway.

CB: Let’s go from the present to the past for a minute. When and where were you born?

WD: I was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, July 1, 1915.

CB: And you’ve spoken of having quite a big family.

WD: Oh yeah, it was a big family. My mother was the mother of 14 kids, but some of them died when they were babies. Her name was Daisy Dixon.

CB: She was an influence on the lyrical side of your songwriting, wasn’t she?

WD: Oh yes. My mother wrote a lot of poems herself, but she was kind of spiritually inspired, with the biblical thing. And I can remember when I was in Jerusalem and I sent her back a bible with one side of the page in Hebrew, the other English. They used to sing songs about Jerusalem in my happy home when I was a kid. And they just accepted biblical affairs as the word, And whatever anyone told them, that’s what they accepted. And accepting somebody’s word without proof today you know what you get!

CB: When did you write your first poems or songs?

WD: I started to write when I was a kid going to school, maybe 11 years old, because I always thought poetic form things were pretty. I had books of the stuff. I thought I could sell it as poems, but you couldn’t sell no poems or nothing in those days.

CB: So when did you add the music?

WD: Well, you know, once you write these things, you keep a lot of it in your mind. They had some people who’d done blues. The world had branded these people lower class people.

CB: Are we talking about the early ’20s?

WD: Oh yeah, because in the early ’20s, I met Little Brother Montgomery. I used to follow Little Brother all up and down. One day they’d be on a wagon bed with horses and mules playing, a piano up there and a clarinet with a guy with a megaphone… They’re going to be playing a dance in the South Side Park in Marcus Bottom. Next two or three days, they’d come on with a Model T Ford truck bed and they’d have the same thing. I was just a barefoot kid. Every night I’d get a whippin’ for being out all day and all night chasing this truck around. And Little Brother he was little at that time!

CB: He was from Vicksburg too, or at least sang the “Vicksburg Blues.”

WD: Actually, he was from Kentwood, Louisana. And we thought because he was little, he was like us. I was bigger than Little Brother, but I wasn’t older than him, My sister would go with me to clubs on Washington Street (in Vicksburg) where they would be playing. Zack Lewis had a place down there. And my sister and I got a chance to meet Little Brother and we made friends and that stuff. He was a little guy, and in those days you didn’t wear no long suits of clothes until you were grown. A boy who was considered a boy, he had the pants that button above the knees. But when he thought he was grown, he could let them button below the knee. And this was the first time we’d seen a Long suit. He had his derby on, and he thought he was really sharp!

CB: Did you go directly to Chicago from Mississippi?

WD: No, the first time I ran away from home, I went out to this place in the country. I was about 12 years old and went to a place called Bovina, about 15 or 16 miles out of Vicksburg. My mother was looking for me, but I didn’t know country kids had to work hard, I thought they had the same thing going for them that we had in Vicksburg, which was nothing. I’d go to school and maybe I’d go get slop for the pigs, and that was it. Anyway, I went out there and that’s where I found out what work meant. Them guys out there were working like mad! I’d never seen the sun rise in my life. But they said they had to make money SO they could come to Vicksburg. I was pretty fat and big, but I’d never done no work! I hadn’t even cut wood with an ax, Eight or ten barrels of charcoal sold for 50 cents! That’s when I started figuring my arithmetic that’s four of us got to split this! And I ain’t got my money yet!

CB: How did you eventually migrate to the North?

WD: The first time I came to Chicago, I was 13. And then I had a sister living here named Katy Gibbs. She had married a guy named Ted Gibbs, and was living at 4716 S. Forestville. I was working on an ice wagon here. They used to have a company called the L&N Ice Co. And at that time, they didn’t have no Frigidaires, man, you had to put the ice on your shoulder and go all the way up to the fourth floor. Most buildings had three floors, but occasionally there’d be a fourth. And it seemed that everybody on a fourth floor wanted 100 lbs.

I grew up doing that. I thought I was making a lot of money but I was making $20 a week. I’d go to school now and then, but my sister was trying to keep me in school, and I wouldn’t go. They finally sent me back home after about a year, and I had to go back to school in Vicksburg. I went back to school there for a while. Thought I was going to be a fighter. And because I’d worked on the boats with those roustabouts they pick up a barrel and truck it on off the gangplank. ‘Cuz I was a big boy, I thought I was a man. I was pretty strong. When I was young, I didn’t want to stay at home too much because my old man wouldn’t be there too much. You saw him about as much as I did! I saw him sometimes, and he didn’t have but a lot of baloney to talk. But he did like the blues. And my mama, she liked the spirituals. When they’d meet, there’d always be some kind of heavy discussion going on.

I’d always be out on my own and I felt I could help the family more by being away than by being there. After I got to fighting, I fought at the YMCA two or three times, and I fought at four or five places around there. And then I came to Chicago. It was around 1936. I had a friend with whom I hoboed to New Orleans in 1935, and we didn’t know where to find nothin’ to eat but at the banana cart and the watermelon cart. I went with the steamer excursion boat going in every night to St. Paul. I came back one day through Rock Island, Illinois, and caught a bus from Rock Island to Chicago. In Chicago, I met my sister. I lived with her, and then I decided I was going to finish my fighting career. I won the Golden Glove in 1937. You see, my name is Willie James Dixon, and I was fighting under the name of James Dixon. People down home always used to call me W. J. Dixon. Well, I did pretty good after I won the Golden Glove.

CB: I don’t know much about boxing. How prestigious is the Golden Glove?

WD: Yeah, the heavyweight champion in 1937! And then, after I won the Golden Glove, I got me a couple of managers. I had about five good fights and then turned pro in 1938. Anyway, after I turned pro, I had three or four really good fights. They were taking a third of my money for management, and so much for my trainer, and I wasn’t gettin’ no money. And on top of that people who’d fought less than me were getting $400 or $500 for their fights. I was getting $200 and thought I deserved more money. One day we were discussing contracts — they had all the contracts written — but the contracts that I hadn’t signed were a subcontract to the ones that they hadn’t signed. We got into a heated discussion, and wound up in a fight. We tore up the office and all got expelled. And at that time I was training over at Eddie Nichols’ gym. My manager really wanted us to cover up his dope racket — and he didn’t really care whether we won or not! But all the while, this fellow ‘Baby Doc’ Caston was playing guitar around the gymnasium. We sat around all day when we wasn’t practicing for a fight, singing.

CB: Were you playing the bass at the time?

WD: No, I wasn’t playing no bass at all. I was just singing. I used to sing bass all the time. So (Caston) said, ‘Hey. You ain’t doin’ nothin’. Why don’t you come out nightclubbing with us?’ I hadn’t ever been in a nightclub in my whole life. So he and a guy named Evan Spencer, we got together and we went all up and down Madison Street, all of ’em, all of ’em down Clark Street, everywhere…We used to sing the Ink Spots the Mills Brothers and everybody.

CB: The Big Three Trio, who you began your recording career with, consisted of yourself on bass, Baby Doo on piano and …

WD: Ollie Crawford, guitar, and also Bernard Dennis — he was the first one and stayed with us a year. Ollie was the second and stayed about six years. Anway, we went all the different places and I found out, hell, I was making more passing the hat than I was fighting. We’d wind up over in Jewtown (Maxwell Street) playing on Sunday with a water bucket and people would fill that water bucket up with pennies, and nickels, and a few dimes, you know. And we just put them in three piles, ‘cuz we couldn’t count all them pennies all day. Then after that we worked with that for a long time.

Before the Big Three, we had another group called the Four Jumps Of Jive, with Leonard, myself, Jimmy Gilmore and Ellis Hunter.

CB: You recorded for Delta Records as the Big Three.

WD: On Delta, it was Baby Doo, Bernard Dennis and my self. And on Columbia, it was Baby Doo, Ollie Crawford and myself.

CB: What was Delta Records?

WD: It was a thing out of Nashville, Tennessee owned by Jim Bullet. He also had Bullet Records. He finally went to New York.

CB: Did he ever do anything with country being in Nashville?

WD: He did some things, like “Near You,” (Begins to sing). Oh, never mind. That was before your time! All along, I’d be writing songs. I’d try and turn them into popular tunes and nobody really cared. We was recording blues, even though we were playing a lot of popular things at the clubs, because when you go place playing, passing the hat, everybody’s got a request for a different thing. And we had to spend a lot of time getting that together. But, we recorded the blues: “Wee Wee Baby, You Sure Look Good to Me,” “The Signifying Monkey,” “88 Boogie,” and “Lonesome Blues.”

CB: What years did you have the Big Three Trio?

WD: Well, we started around 1945 and it went til about 1951.

I had a load of songs — I’ve had a load of songs since I was ten! So as everyone came along, I had a song for them.

Willie Dixon

CB: Is that when you went over to Chess Records?

WD: Yeah, that’s when I started working at Chess, while I still had the Big Three Trio. Because I played pretty good bass. We was right out there on Madison Street, just gigging up and down there, me and Baby Doo. He made me a tin-can bass with just one string, and I played that thing all over Chicago. In fact, I’ve been trying to find somebody that has pictures of me on that tin can! Anyway, we used to jam with Muddy Waters when he first started out.

CB: While Muddy was on the Aristocrat label?

WD: Well, Muddy wasn’t on no label when we were jammin’! Him or Walter either. We went over there on 35th Street, over on the street where they cut the Dan Ryan Expressway, next to Jefferson — What was that? I know it when I hear it called. Anyway, we jammed with Muddy and one day he got ready to record, and he told Chess to call me up and see if I could play bass on his session. Well, he had recorded a couple things ahead of that time. They called me in Omaha, where I’d been working…

CB: Omaha?!

WD: That’s right, Omaha, Nebraska. I was working at the Dundee Dell. So I came back and recorded with Muddy Waters and Robert Nighthawk. Nighthawk recorded that thing about ‘Sweet Black Angel.’ And then he had some girls singing behind him. Well, we’d already recorded ‘Wee Wee Baby, You Sure Look Good To Me’ for both Delta and Bullet, which was the same company, and Columbia too. Then Baby Doo started having matrimonial trouble with his family. And every time we’d get on stage, there’d come the police and drag him off the stage. So we (the Big Three Trio) gave up for a while and I started working with Chess.

CB: Baby Doo’s in Minneapolis now..

WD: That’s right. Incidentally, just three weeks ago (approx. Oct. 17), he had a heart operation, a bypass. I was talking to him the other night and he said, ‘Man, I have a new carburetor and everything and I’m rearin’ to go!’ He said the peculator’s working good and they got him walkin’ around!

CB: You were hired by Chess specifically as a bass player?

WD: As a bass player. After they found out I was on the loose, I got a contract from them as a producer. And I was told the contract was as producer, songwriter, and all like this. He started me and had me listen to the artists and see what I could make out of some of the songs they had, or if they didn’t have songs that were properly sufficiently, to try and write songs for them. I had a load of songs — I’ve had a load of songs since I was ten! And somehow or other, it looked as if some of them reached different (artists). So as everyone came along, I had a song for them. Even Leonard Allen at the United/States label wanted a few. And that’s the way it went, up until Leonard (Chess) died. Then I worked with the company a while longer.

CB: You did a few songs as a performer on Chess, but not many Why was this? What was (Dixon’s talking blues single) “Walking The Blues” about?

WD: I did some on Chess. But the thing about it was that Chess found they could use me more in the studio than a would-be artist, so that’s why they kept me in the studio and payed me a salary there. I figured it was a good thing because I got a pretty straight salary there. And I worked on salary until after Leonard died. At the same time, I was writing my own songs. I was with Arc Music — he and Chess had a deal. Under Arc Music, all my music was my own.

CB: Was it? But you have your own publishing company now.

WD: Oh yeah, I have my own publishing. Most of the songs that they had of mine, In fact all of the songs I don’t have, I will have in just a matter of time. (Ed. note: This was true when diligent manager Scott Cameron tirelessly helped Dixon receive rights and revenues.)

CB: You played bass on a good portion of the Chess output. Did you play any electric?

WD: No, mostly upright.

CB: Did you ever play electric?

WD: Well, I had one for while but I never did get accustomed to it, because I sold it to Jack Meyers. I had one of the first because the company wanted me to try advertise it, but I never really did get to it because it looked like it took all the show out of my field. I like the sound of (the upright bass) better on certain things, because I could get a better slap sound out of it.

CB: In your new group, your son Freddie plays electric bass.

WD: Right, but I still do occasional things on my bass.

CB: Who’s in your current group?

WD: Right now, I have my two sons, Freddie (bass) and Butch (piano). I also have Johnny Watkins on the guitar. I use two harmonica players Snooky Pryor and Billy Branch.

CB: You’re the one who brought Snooky Pryor out of retirement.

WD: Right, and Billy Branch too! Billy really wasn’t playing very much harp when I get him. But you know, after a lot of rehearsals, anyone can come out of retirement. And I have Tim Tilman on the drums.

I just want to know why the great countries of the world say they want peace and end up making war. Now why? That’s the only question I want to ask them is why!

Willie Dixon

CB: Your last album was the one on Ovation Records, What Happened To My Blues, right?

WD: Oh yes, the last I actually released was on Ovation. Now I have a new one I just finished last year called A Mighty Earthquake, A Hurricane. This is supposed to be released in England. And then it’s supposed to be released in the States too with Stan Lewis, Jewel Records. But I’m going to Washington on Feb. 4 & 5, and I’m going to release a special on “It Don’t Make Sense, You Can’t Make Peace,” and the other side, “It’s in the News.” And I’m going to see that everyone in Congress has one of those! And I think it might make quite an impact. I just want to know why the great countries of the world say they want peace and end up making war. Now why? That’s the only question I want to ask them is why!

CB: I wish I had an answer to that one.

WD: But it don’t make sense. You take big countries, small countries, medium countries and they say they want peace. And they have scientists and wise men and smart men, Democrats and Republicans…

CB: And then we have presidents!

WD: And still, nobody can get together to make peace. They ain’t talking about stoppin’ war. Why they going to limit arms? Why make something they say they’re not going to use? Why they can’t make peace? They can make everything else. They can even make babies without men now!

CB: As a bit of a nonsequitur, let’s talk about the final days of Chess Records. You were there after Leonard died?

WD: I was there after he died. Leonard ran that company. There were a lot of understudies around there, but they really didn’t understand the business like he did. After you’ve done business with the headman and then you have to do business with a substitute, you don’t come up with the same agreement. It’s that simple. Phil (Chess) took it over. Marshall (Leonard’s son) didn’t do much because he was on the move all the time and youngsters didn’t have very much time for it in the first place. I think the only reason Marshall was in it was because he was forced in it. It’s like my kids they wouldn’t give a doggone about the music or nothin’ else. They were forced in it because if you’re going to get around me, you got to play music. Or work. So they’d rather play music than work.

CB: Was it during or after Chess that you recorded I Am The Blues for Columbia?

WD: I’d written the song long before they had it. I did that album on Columbia for what’s that guy’s name? He’s out in California now?

CB: Norman Dayron?

WD: No, this was another guy. He leased it to Columbia. He used to work around there at Chess occasionally. An Italian fellow… Who was that blond guy who sang…?

CB: Johnny Winter?

WD: No, not that blond! Less blond! Big guy, muscles.

CB: Wayne Cochran?

WD: Yeah! The guy who managed Wayne Cochran. Anyway, he said, ‘You’ve written all these songs for other people but you’ve never done ’em yourself,’ And I told him I’d done ’em all at different times but no one had put them all together.

CB: Were you satisfied with your Columbia relationship?

WD: I was so-between I’d recorded for Columbia years contact. But it’s better to be a big fish in a little pond than a little fish in a big pond. In a big pond, like Columbia, A little guys like me got eaten up by big fish.

CB: From there, you started putting out records on Yambo.

WD: Right.

CB: How long have you had this storefront, the Blues Factory at 7711 S. Racine Ave.?

WD: About ten years. It was a practice studio because there were so many musicians who didn’t have a place to practice. But we had a free studio down there, and I kept my own band rehearsin’ and making new tunes.

CB: What was this building before you converted it to the Blues Factory?

WD: It was a store. They had shelves all around the wall and everything. The lady got held up a couple of times and figured she’d get rid of it. I ripped all the shelves off the wall and kind of padded it and we’ve had band rehearsals in here a long time. When the Union had free band rehearsal space, everybody would use it. But when you started putting a tax on it, nobody showed up. So I just used it as a Blues Factory, where I just made songs. And whenever I feel up to par, I come in here and get ideas and hide from all my friends and write a song.

CB: I followed you through the Yambo label. What was the Spoonful label? A continuation?

WD: I did a few things on Yambo but I never did actually go out to sell very many of these things. I attempted to, at first. But when you got to the various disc jockeys that you think are going to promote things, you can forget about It if you ain’t got no money! And I didn’t have no money to pay no money. I still ain’t got no money to pay somebody to play a record. The big companies can afford to pay these guys because the disc jockeys know that while he’s playing my record, he could be playing somebody else’s record and get a dollar off it ‘cuz he can’t get no dollar off of me. And, if he plays my record, he figures I may not have another record but the big companies gonna have one and that’s why he plays the big company’s records.

CB: How did you end up on Ovation Records in the ’70s?

WD: It’s okay…I’m waiting on a statement from them. Haven’t had but one statement from them. They owe me a statement; then I’ll know something.

CB: Next question…Will we ever see your book on the blues on the stands?

WD: Oh, sure. One day. No prediction on time, though, because I’ve gone into so many different things such as this Blues Heaven Foundation which has required quite a bit of time.

CB: You’re called the Master Story Teller, and I hear you’re doing some work on the college lecture circuit.

WD: Well, this is because of the many stories of the blues. When you really figure them out, all the stories and the songs, each is the story of somebody’s life one way or another. If it’s not a story of life, it’s a part of life. One guy tells you a story about his old lady left him and he got happy. The other one, his lady left him and he didn’t get happy. And the other, his old lady came back, and that was the wrong thing to do! Even in the political thing, the condition of the world is another blues fact.

And everything life consists of is another phase of the blues. So your blues may be different from mine, but if we reach a mutual understanding, sooner or later we’ll be able to understand each other’s blues.

CB: You won some awards at WXOL’s recent Blues Awards banquet.

WD: Oh, yeah, that was…I don’t know how they got that thing together, but that was a damn thing I paid to be on! Hell, I sent them $125 of my money and they sent me a damn award I could get for $15! I think that’s just something somebody’s trying to sell on some poor folks and thinks this is a fast way to get some.

CB: You had a column in Living Blues magazine for a while, blues questions and answers.

WD: Yeah, I had it for a while. It was never a big thing. It was a free thing. I was answering the questions. Once in a while, one of them asks me different questions. But I’ve got a lot of questions I’m going to be asking real soon, especially why the world can’t make peace.

About the author: Cary Baker, who conducted this interview with Willie Dixon at age 16 in 1971, is the retired founder of Conqueroo, a leading roots music publicity company named after a lyric in Dixon’s “Hoochie Coochie Man.” A Chicago native, Baker wrote for publications like Chicago Reader, Creem, Billboard, Record, Bomp!, Trouser Press, Goldmine, Hit Parader, Mix, Illinois Entertainer, Living Blues, and more. He worked as head of publicity at Capitol Records, I.R.S. Records, Enigma, Morgan Creek, Discovery and Ovation Records [Capitol and Ovation released albums by Willie Dixon].

A lifelong collector and blues enthusiast, Baker long considered Dixon a surrogate father; the two Chicagoans later, coincidentally, ended up as Los Angeles residents. This was one of two or three interviews Baker conducted with Dixon, since they met when Baker called Dixon out of the phone book to invite him to appear on his high school FM station, WNTH-FM in Chicago’s suburbs. Upon retirement, Baker is at work on two books and a reissue project.