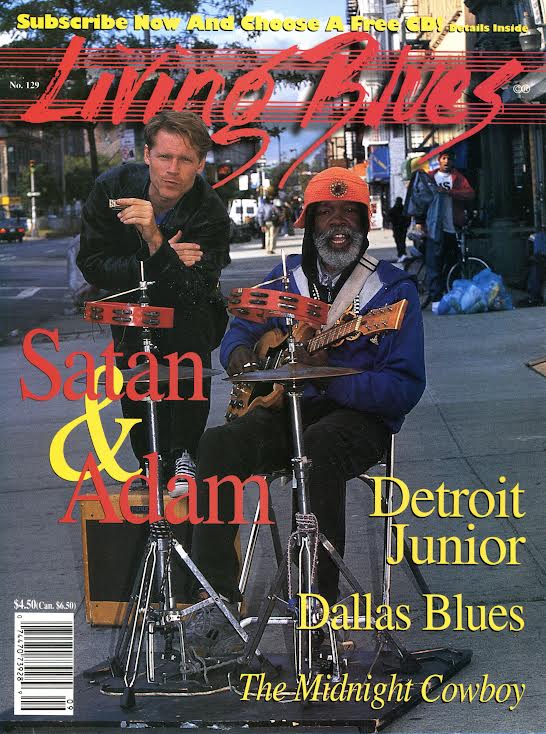

Adam Gussow, a blues harmonica player, is known for his partnership with Mississippi born guitarist Sterling “Mr. Satan” Magee as the duo Satan and Adam. A full-length documentary titled Satan & Adam premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival and streamed on Netflix from 2019 to 2021. The duo toured with Bo Diddley and opened for Buddy Guy, David “Honeyboy” Edwards, Otis Clay, Johnny Winter, and Jimmy Thackery.

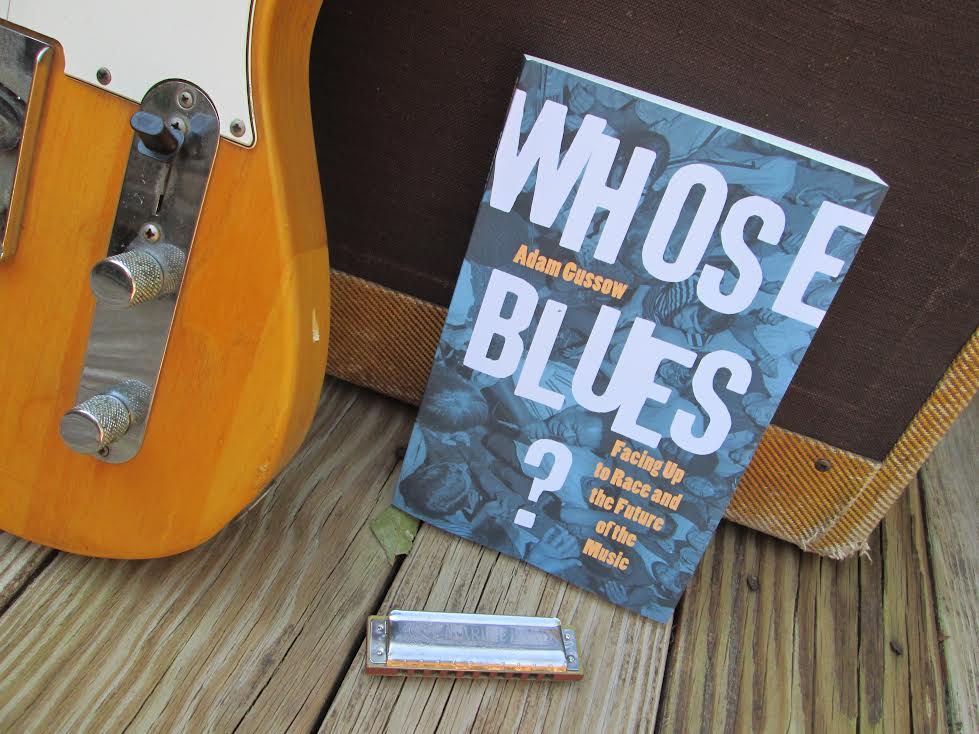

A scholar and memoirist, Adam is a professor of English and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi. He’s written the following books: Mister Satan’s Apprentice: A Blues Memoir, Buskers Holiday, Beyond the Crossroads: The Devil and the Blues Tradition, and Seems Like Murder Here: Southern Violence and the Blues Tradition. His most recent book, Whose Blues? Facing Up to Race and the Future of the Music, empathetically confronts racial issues within the contemporary blues music community and blues music of the past.

His book takes an in depth look at two slogans and studies them from multiple perspectives; “Blues is Black Music” and “No Black No White Just the Blues.” Gussow currently plays with Sir Rod & The Blues Doctors. The trio consists of Mr. Satan’s nephew, Rod Patterson on vocals, Alan Gross on guitar, and Gussow on harmonica and drums. Their live album, Keeping It In The Family, is now available.

Can you talk about your book Whose Blues?

The original title was Blues Talk: Making Sense of The Music In A New Millennium. I was interested in the ways we talk about Blues in a contemporary conversation. My publisher said, “I think we need to make the title a little sexier.” Whose Blues? Facing Up to Race & The Future of the Music was what we came up with. It makes the book sound like a contest, and that’s not wrong. What I was interested in are the two prevailing ways in the contemporary blues world in which we ideologize the blues–not the way we consume the blues, but the way we frame the blues with big ideas and argue about it. It struck me that there are two main ways we do this–a pair of t-shirt memes, in a sense. First, there’s Corey Harris’s phrase “Blues is Black Music” with an emphasis on the word Black, as though somebody is shouting “Stand Back!” (Yosemite Sam would say, “Back off!”) The other meme–it’s not something I’d say, but I understand where it comes from–is “No Black. No White. Just the Blues.” We’ve all seen that t-shirt and bumper sticker! What I was interested in is the conversation that emerges when you try to take both slogans seriously.

I can imagine some people immediately taking sides and thinking, “Well of course blues music is Black music.” And of course, at some level it is and always will be. Ninety three percent of the people in the Blues Hall of Fame in Memphis–the great innovators and stars–are African American. That’s justice. In the early days, blues was black popular music. W.C. Handy, Bessie Smith, and Ma Rainey popularized it. Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues,” in 1920, which featured a Black female singer and an all-Black band, catalyzed the race records market. On the other hand, there is history and its complications. In the course of the 1960s, the mainstream audience for the blues flipped. In 1958, it would have been ninety eight percent Black.

By 1970, B.B. King noted that his audience had changed from all-Black to mostly white. Certainly, this was true at the new venues he was playing. With an incoming new cohort of white musicians and even Japanese musicians in the late 1960s, blues became more of a mainstream thing. In the mid 1970s, blues societies were formed and they were almost all dominated by white fans. You have a transformation of what had been a kind of Black thing to a mainstream thing in which Black musicians are still very much a part of what’s going on, but Black audiences have significantly melted away.

Blues is global music too. It’s global folk music and it’s big in Japan; it’s big in all the places B.B. King spread it during his many overseas tours. I wrote about this in an article called “Bien Al Sur: Notes Toward a Genealogy of Blues, Music’s Global Spread.” So given all this, what’s the problem with the phrase “No Black. No White. Just the Blues?” Well, why do blues tourists come to Mississippi? Do they come for Harmonica Frank Floyd? No! They come for the overwhelming number of remarkable Black artists who made music there. The phrase “No Black” seems to want to start by erasing blackness. By the same token, blues is a place where Black and white, gay and straight, working class and middle-class, and foreign and domestic can all get together.

Someone like Ken Kawashima, who I write about, is an American born product of a Korean and Japanese marriage. He now lives in Canada and he is a wonderful blues artist. He played with Tail Dragger in Chicago and paid his dues in the Chicago Scene. I’m interested in these paradoxes. He’s not Black, but he’s paid his dues and he can sing and play the blues. I try to go back into history and think about the origins and historical development of the blues. I deconstruct every perspective, to some extent.

For example, I discuss a book called Long Lost Blues by Peter Muir in which he goes back and looks at the phrase “I’ve Got the Blues.” He discovered that this phrase first shows up in sheet music in 1850 with a German American composer. He argues that white folks were talking about having the Blues, at least in song lyrics, long before Black folks were. I don’t know if everybody knows that. The Blues, in the late 19th Century, was a nervous disease that well-off urban white people had. Then it became something that people sang about. I discuss an early white recording artist, Marion Harris, who was recording in 1917. Because of the racism in the recording industry, white women got on record before Black women; their voices partly helped shape the emergent tradition.

I’m an in-the-weeds kind of guy. With Whose Blues I really wanted to get deep into this conversation and take it seriously. I was prompted to do this by a “Blues & the Spirit” conference that my friend Janice Monti organized at Dominican University in 2012, which featured a blues panel called “Opening Plenary: Blues Summit on the State of the Music Today.” A number of African American artists sounded off, talking frankly about problems in the contemporary scene. I try to arbitrate some of those issues in my book, including the phenomenon of the all-white blues festival. But I also talk about the facts that Billy Branch and Sugar Blue played at a harmonica festival that I created, Hill Country Harmonica, which specifically focused on African American players. They were silent about it during the panel. Sometimes complaints, which are valid, are also partial and mask other countervailing dynamics.

On this point–and this happened after my book came out–Rolling Stone recently published an interview with Carl ‘Buffalo’ Nichols titled “So Much Damage Has Already Been Done: The Fight To Reclaim The Blues.” Nichols is a highly politicized contemporary African American performer and a very good player. Kingfish, who is a fantastic player as well, said, “The genre is dominated by nothing but Caucasian people; the festivals, the organizers, the record people. Everyone’s Caucasian.” Here is what is wrong with that and what needs to be said. There are actually two contemporary Blues scenes. One of them is the mainstream scene.

Over the past fifty years there has been a lot of sweat equity put into that scene, some of it by the white folks who founded blues societies and invested money to put on festivals, create recording labels, and set up booking agencies. Sometimes this white-folks-presiding dynamic ends up resulting in all-white Blues festivals, but that isn’t common. There are some terrific promoters who happen to be white, who know what great blues is, and who regularly hire African American performers. It is also true that this mainstream scene and its audiences are more white than not.

The promoters are trying to give those audiences what they want. I can only imagine that a younger Black blues performer who wants to play a certain kind of music, maybe with a political overtone, may feel frustrated because maybe that audience isn’t responding to them. (That audience loves Kingfish, of course; he’s an incredible singer and player.)

There is another blues scene, however, and it is essentially an all-Black blues scene. Anybody who lives in Mississippi knows that it’s on the radio all the time. The music is called Soul Blues and Southern Soul Blues, or just blues. It features a range of performers that are almost completely unknown to white audiences. They are not hard to find if you know what search terms to use. The promoters, people who run the festivals, managers, and record labels are almost all Black. Black blues players like Marquise Knox, Christone ‘Kingfish’ Ingram, Sugar Blue, and Billy Branch don’t have name-recognition on this all-Black circuit.

The music they play is grounded in a different approach to the Blues. There are a few places where the two scenes come together. Bobby Rush is the best living example of this. He crossed over from the all-Black Scene, the Chitlin’ Circuit, to the mainstream circuit. Nellie Tiger Travis has a presence on both scenes. The Jus’ Blues Music Foundation in Atlanta is trying to bring both scenes together, and that’s a good thing. The Southern Soul-Blues scene has very few white artists that have managed to break through. They just don’t even try. They don’t really do what that audience wants. So white artists are essentially shut out of this all-Black blues scene.

What we are left with, all the rest of us, is the “mainstream” scene that is filled with various kinds of complaints and problems, as Black and white artists, making their best music, are competing for gigs and recognition and market share. This mainstream free-for-all just is what it is. This Blues scene has the Blues in certain ways. This is what my book Whose Blues is all about. I raise all of these questions pointedly, with compassion. Ultimately, my desire is to tell the story of the music as honestly as I can and figure out where our common ground is.My own experience teaches me that blues can be a place where Black and white and everybody else come together fruitfully and joyously.

This is true not just from my several decades with Mr. Satan and the recordings we did, the many shows we played, the awards we won, or the Living Blues cover-story we achieved. I’ve had a longstanding friendship with a younger African American artist named Brandon Bailey which began when I produced his first record. He’s combined Hip Hop and Blues. He’s beatboxing the Blues. We actually met through YouTube–a comment he made on one of my videos–but we’ve become good friends. In my book I wanted to talk about the way Blues works in the post-modern age and about the way, at best, that the music genuinely promotes brotherhood.

How is blues received through your teaching at The University of Mississippi?

I’ve been working here for twenty years. In the English Department I teach undergraduate and graduate courses on the Blues literary tradition. In my Southern Studies courses, I often use Honeyboy Edwards’ Autobiography, The World Don’t Owe Me Nothing. If somebody is looking to read what I consider the great Blues autobiography, that’s it. Honeyboy knew everybody who was anybody, and he came up right when Blues was emerging as a musical force in the Delta. B.B. King’s autobiography is good too, but Honeyboy’s has something different. He really makes you understand what the music did for him. You asked how my students receive this material.

Well, they get that cotton sharecropping was a tough business! It wasn’t fair to most of the Black folks who were forced into it. Honeyboy used his creativity and figured out a way of circumventing that exploitation. He realized that if you could be an independent contractor, busk for nickels and dimes the way Robert Johnson did, play what the public wanted, and be a human jukebox/songster, you could actually make a life for yourself. Honeyboy learned how to hustle from Big Joe Williams. By the time they finish Honeyboy’s life story, my students get why he called it The World Don’t Owe Me Nothing. You would think the title should be I Can’t Be Satisfied, given what we know about Blues and oppression. But it’s the opposite. Honeyboy figured out how to survive and even prosper in his own way.

What is also buried in this text, and in W.C. Handy’s Father of the Blues, are these forthright descriptions of horrific racial violence. Honeyboy talks about a friend of his named Quack who didn’t want his pregnant wife to work in the field. The bossman told him that she was going to work in the field, and they ended up getting in a fight. The guy ended up killing the bossman, at which point some white men tied him to the back of a car and dragged him into town. As Honeyboy said, “There wasn’t nothin’ left of his face by the time they got there.” These autobiographies are a good way to introduce to students what I call the key Blues condition: having to worry about Jim Crow violence, the kind of violence that might jump on you at any time.

When I teach the Blues Literature class, we read poems as well as novels. We read August Wilson’s play, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. My first book was about southern violence and the Blues. Blues literature is a way showing students the wounds and trauma and how Blues people dealt with it.

We also study The Black Arts Movement, although we start off earlier than that with poetry from Langston Hughes. I help students understand that there was an argument within the Black intelligentsia in the ‘60s. Whose Blues talks about this too. Some people like Ron Karenga, who later created the holiday Kwanzaa, put down the Blues. He said the Blues were politically invalid and encouraged people to sing and complain rather than acting forcefully to combat their oppression. There was a way thinking in the ‘60s that encompassed this.

By the same token, you have Larry Neal: a great Blues theorist and defender of the Blues, and a key member of The Black Arts Movement. He insisted that the blues is Black history and a site of resistance. It is a way of keeping spirits alive when it looks like everything is against you. Blues is a way of keeping the energy flowing, and the beat is a part of that. The students know that there is sadness in blues but also there’s a point that Albert Murray made which is there is a difference between having the blues and expressing those feelings musically. When you express them in community with call and response, it can purge you and even heal you.

I invite blues musicians to my classrooms. I had Bill “Howlin Madd” Perry, who is a local guy, and his daughter Shy Perry. I have known Bill for twenty years. He came to the classroom and told some wonderful stories. I shared one of them in Whose Blues. It is a story about being abandoned by Little Richard on the road. Bill was in his touring band. His story was great because it wasn’t coming from a book, it was from the life he’s lived. After being abandoned by Little Richard and the band in Los Angeles, Bill had a dollar in his pocket. He bought breakfast for ninety cents. He then went on the road–literally out on the highway in Los Angeles–and started walking. Because he had been in town for a week playing with Little Richard, someone recognized him from the club and picked him up and let him stay at their house for a week. He scrounged some money together and then went back to Chicago. That is a blues story! Rather than sitting and suffering, Bill got up and got moving.

The blues speaks to me. It’s an attitude and practice, almost a kind of spiritual exercise. Of course, it is music too and can be taught but it’s not like any other music. That’s its own challenge. Over the last thirty years I have taught a lot of Blues harmonica and I think I have figured out a way to get people through the door.

How did your new band Sir Rod and The Blues Doctors come to fruition?

Keeping it in the Family is our second album; it’s the follow up to Come Together. It came to fruition after getting together for the first time in early January 2020. This was before anyone was paying much attention to the pandemic. We ended up cutting six or seven songs one weekend and realized we had more than a demo. Rod Patterson came back a month later and we put together another three or four songs. I’ve produced a fair bit of music over the years.

I’ve done close to ten albums. I worked with recording engineers here in Oxford and I have a good mastering engineer so I know the process. I was dubious at first when Rod said he could do it. With the Blues Doctors I play drums with my feet, Alan Gross plays rhythm guitar and some leads, and I play amplified harp.

We don’t have a bass player. Rod was a championship dancer doing Michael Jackson stuff as a teen and early 20-something, and he sang some R&B back then, but he had no experience in a live blues context. For seven to eight years, he was doing karaoke singing and dancing along to tracks by Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, James Brown, and Michael Jackson. Around three to four years ago, he started singing instead of lip-syncing. And by the time he showed up to jam with Alan and I, after woodshedding with a bunch of old Satan & Adam CDs, he had it.

Somehow everything in the studio just clicked. When recording there is always something that goes wrong. In this case it didn’t happen. It just fit together and we had so much fun. He doesn’t sing like my old partner, Mr. Satan, but he has his own style. People say he sounds like Sam Cooke. He has a Soul version of a Blues voice. We play “What I Say” and “Shake Rattle Roll” is the lead cut off the new album. I defy anyone to listen to that and not feel good. It is the kind of blues that makes you feel good and want to dance.