Editor’s note: This is part two of our interview with the scholar, memoirist, and blues harmonica player. You can find part one here.

Adam Gussow is perhaps best known for his partnership with Mississippi born guitarist Sterling “Mr. Satan” Magee as the duo Satan and Adam. A full-length documentary titled Satan & Adam premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival and streamed on Netflix from 2019 to 2021. The duo toured with Bo Diddley and opened for Buddy Guy, David “Honeyboy” Edwards, Otis Clay, Johnny Winter, and Jimmy Thackery.

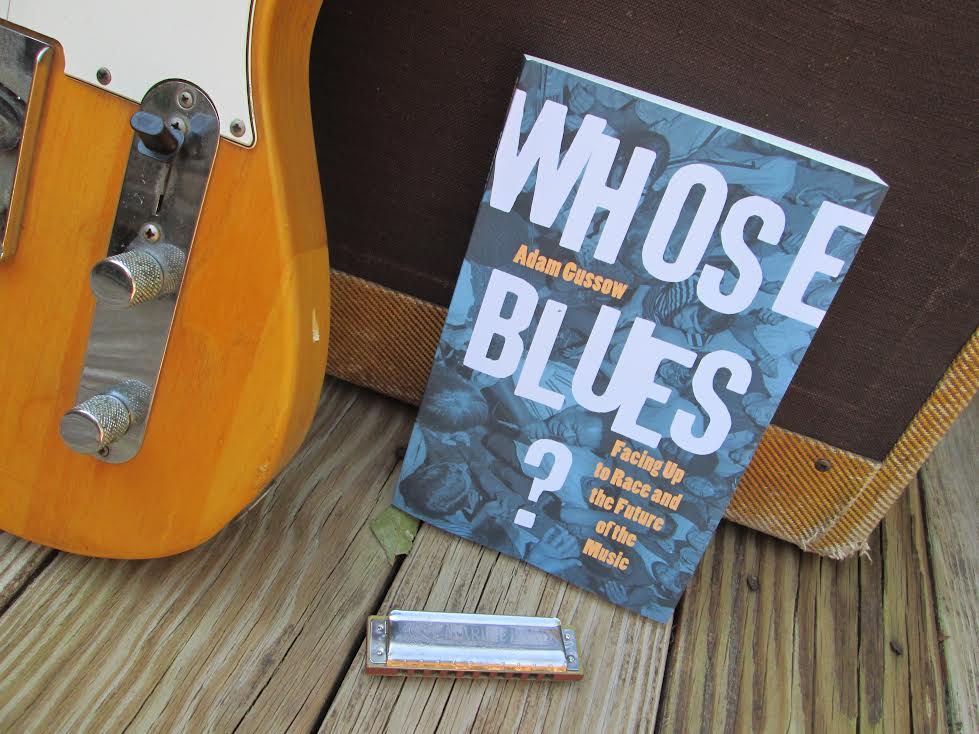

A scholar and memoirist, Adam is a professor of English and Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi. He’s written the following books: Mister Satan’s Apprentice: A Blues Memoir, Buskers Holiday, Beyond the Crossroads: The Devil and the Blues Tradition, and Seems Like Murder Here: Southern Violence and the Blues Tradition. His most recent book, Whose Blues? Facing Up to Race and the Future of the Music, empathetically confronts racial issues within the contemporary blues music community and blues music of the past.

His book takes an in depth look at two slogans and studies them from multiple perspectives; “Blues is Black Music” and “No Black No White Just the Blues.” Gussow currently plays with Sir Rod & The Blues Doctors. The trio consists of Mr. Satan’s nephew, Rod Patterson on vocals, Alan Gross on guitar, and Gussow on harmonica and drums. Their live album, Keeping It In The Family, is now available.

What are your favorite songs from Keeping It In The Family?

I would say our song “Come Together,” the title track from our first album, but we also cut a live version for this new album. It is not a blues at all. Imagine a song that consists solely of four major chords with no bridge. The chords consist of the I, bIII, IV, and bVI, on and on and on. It sounds and grooves sort of like the breakaway section to “Free Bird.” I think “Free Bird” is I, bIII, and IV. So, it sounds a little bit like that, but it has a kind of power that grows and grows as the song blasts along.

I had come up with this chord pattern, and Alan and I put it up on YouTube. It had about two hundred and thirty likes and one dislike over the last few years. So, I sent it to Rod and asked if he could write some lyrics. And he did, literally overnight, and it’s a heck of a song. It’s a prophetic song that speaks to America’s divisions. It tries to get us to come together to solve them. It speaks to Covid too, which is really weird as Rod wasn’t thinking of that when he wrote it. I love playing it; I love the driving groove. It is almost like a Blues Traveler song. It’s a jam band anthem! That is what the recording engineer said. I don’t know what the blues audience thinks of it, but it should have some crossover appeal.

You play music, write about it, and teach. What do you get from each?

I love playing with this trio and I love giving something to the audience. Stanley Crouch used to talk about Blues as having “the big feeling.” If you think of Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, B.B. King, or Albert Collins, there’s something explosive in all of them. I like that–the feeling of power in the music. The longer you play this music, the longer you live, the more you’re forced to confront the number of musicians who have passed from the scene. I think about Joey DeFrancesco who just died, a great organ player.

There are so many musicians who have passed on. A lot of harp players I knew from New York are all dead. I feel the vibes of keeping the ancestors alive sometimes. It sounds strange but I feel it. I know that Sterling would have been incredibly happy to see what we’re doing, Rod and Alan and me. I like connecting with and making the audience feel good. I have been happily married for eighteen years and I don’t have the blues in the same way I did as a lonely single guy hoping the great love would come along. You play from different places in your spirit at different points in your career.

As far as teaching goes, I assume we’re talking about YouTube where I have done hundreds of instructional videos. There are lots of people doing it now, but when I began in February of 2007, there was nobody on YouTube trying to teach blues harmonica. There was Ronnie Shellist with his one video “Funky Blues harmonica” where he was just jamming along. But there was nobody offering step-by-step guidance on how to play. For some reason I was moved to try to share what I knew.

My buddy Jason Ricci came on board soon after, and he has done his own amazing teaching thing over the years. Ronnie, too. There are lots of other players out there doing it now and I think that’s great. Back to the idea of sharing: I always found it easy to speak to the camera. I love to explain shit, like the village explainer. I’ve been well enough trained on the instrument, too, that I can make the right sounds. I think harp players should get guidance from someone who has actually learned how to play the music. It’s very different if you’re mentoring the person one on one. Some people want to just watch videos and not put in the hard work. Most people I know didn’t learn by playing videos–although a few really good players have told me they started learning from my videos. As a scholar, I like to explain and clarify. I’m a fact-based guy. I try and see through myths to explain deeper truths.

What will contemporary Blues music look and sound like in fifty years?

What I write about in Whose Blues is that the way people are learning to play blues music in the digital age is very different from how the music was passed along for most of human history. In this age of social media, if there is a ten-year-old kid who wants to be the greatest harmonica player in the world, there is the internet. How would that work for a kid in Chicago in the 1950s? Think about Billy Boy Arnold. You had to find the players in person and watch them play. If you were lucky enough you met Little Walter, and if you were really lucky he might show you something–or not.

Now you can go online and see everybody all at once, the whole history of blues harmonica at the highest level. You can google ten-year-old harmonica players and find the other kids that are your age. This dynamic holds true for people all over the world. I have talked about Luna Lee in my scholarship about the Global South. She’s living in America now but she grew up in South Korea. She is a Korean YouTuber. She has done a lot of blues Rock stuff but also likes Elmore James and Albert King. She plays gayageum which is a Korean traditional instrument that has an eerie, harp-like sound. People should check out her version of “Dust My Broom.” Some blues in fifty years may sound like this; people doing bluesy things on different, non-standard instruments.

I think blues tonality will endure, along with certain blues grooves like the shuffle. Blues tonality is the way we will always know the music. The slide guitar sound and the squeezed guitar notes may show up in unexpected places. Luna Lee has the microtones, but she gives them a very weird spin. The phrase “Blues Is Black Music” will always be relevant. The great ancestors will always be Black American Blues players. Blues loves to think about its ancestry and harken back to the early days, which is so curious because in its time blues was a new sound. It was as much a new sound as it was an old sound. It has always been a bit of both.

Blues will continue to want to recreate an old sound. On this point, Marquise Knox, Kingfish, and Jontavious Willis did a remarkable thing. A few years back down in Cleveland, Mississippi, they did a tribute to John Lee Hooker, which I was lucky enough to be present at. There aren’t three white blues musicians their age on this planet capable of doing what they did. They reanimated the spirit of John Lee. It was uncanny. I have great respect for what they did. In a funny way there is no need to get racial when you’re capable of making music that good–as long as you have audiences of whatever persuasion that can actually hear just how good you are, and how powerfully you’re conjuring up the ancestral spirits.

What’s next for you?

I think I may have written my last blues book for a while. My friend Patrick Alexander, a professor here at Ole Miss, created a program called The Prison to College Pipeline about a decade ago. He brings Humanities professors into Mississippi State Penitentiary, a.k.a. Parchman Farm. They teach courses to the inmates. I found out that I am going to be teaching my blues literature course there in the spring. I know I will learn a lot, and I know that my students, with all their life experience, are going to have powerful things to say about the material. I’m looking forward to it.