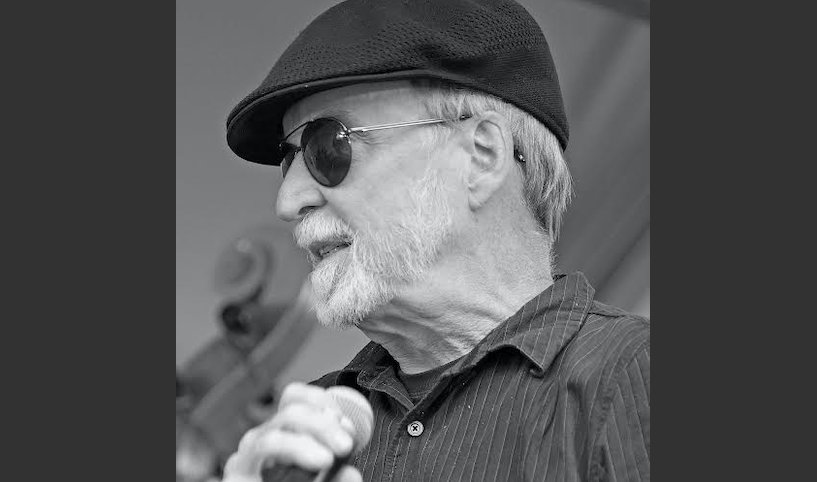

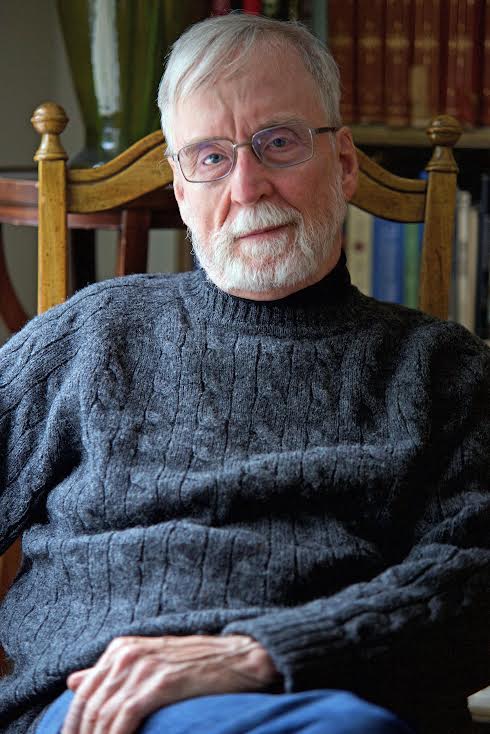

David Whiteis is a Chicago-based writer, journalist, and educator. His books include Chicago Blues: Portraits and Stories, Southern Soul-Blues, Blues Legacy: Tradition and Innovation in Chicago, and Always the Queen: The Denise LaSalle Story. Currently a writer for The Chicago Reader, his articles have also appeared in numerous jazz and blues magazines. In 2001, he was the recipient of the Blues Foundation’s Keeping the Blues Alive Award for Achievement in Journalism.

What drew you into writing?

I have always loved writing; I always got As in English in school. But it’s a crazy story and has nothing to do with blues, actually. When I came back home to Connecticut from college in the mid-seventies, I found out that Leonard Cohen was going to be playing at the Shaboo Inn in Willimantic. That was in 1975. Cohen was one of my favorite artists at the time, and I’d always wanted to be a writer, so I called the Hartford Valley Advocate, which was Central Connecticut’s weekly newspaper, and I basically sold myself unseen. I told them I knew his stuff really well, I’d read his poetry and his novels and I knew all his music, and I could do a good article on him.

I went up and interviewed him, and I had no idea what I was doing – I’m sure I came on like some ungodly combination of Jimmy Olsen and the Geek from Hell. I didn’t know how to structure an interview, I didn’t know how to phrase my questions, I didn’t even have it together to record the conversation properly. He had every right to say, “Who is this kid? Get him out of my dressing room!” But he was incredibly giving and charitable – I remember him saying very kindly at one point, “Could you please rephrase that? I don’t know what you mean” – so I felt encouraged, and I survived it because of that. I owe him a lot, not just because it was my first gig, but because he was so encouraging. He treated me like I was a real person, someone who could actually do him some good.

And I guess it worked, because the article was published, and that was the beginning of everything. I would like to say it was Muddy Waters who gave me my start, but it wasn’t. It was Leonard Cohen.

What attracted you to blues music?

I won’t say it was any one thing. It wasn’t the old cliché that it was sad or mournful. I grew up with sad mournful music. Remember, I was a big Leonard Cohen fan, so I didn’t need the blues for that! Basically, as I got more knowledgeable about American music, a lot of it had roots in Black music – soul, R&B, gospel, jazz, blues – basically almost everything we think of as “American music” has Black roots. And it’s not just the music but the history, the culture, the entire historical legacy. Blues history is Black history, which is to say, American history.

At the Shaboo, back in the seventies, a lot of great artists were coming in. People like James Cotton, Buddy Guy and Junior Wells, Muddy Waters, and Bobby “Blue” Bland played there. I started seeing the music, experiencing it, and I became more and more drawn to it. I was fortunate enough to meet some of these great musicians, and I became interested in them and their life stories. The more I listened, the more I learned; the more I learned, the more I listened, and the more I read. Pretty soon, I was immersed.

If you want to fast forward – I told this story in Blues Legacy – in 1978, I’d moved from Connecticut and was living in Boston. I went to the Speakeasy, a club in Cambridge, and Eddie Shaw and the Wolf Gang were there – Hubert Sumlin on guitar, Shorty on bass – and something struck me in the way that band sounded. I just immediately said, “I have to go where this music came from.”

I went home that night, and I applied for a job in Chicago at a community organization. They called me to come out there in January. It was the Blizzard of ‘79, the big one, when the entire city was shut down for two weeks. I think I came in the very first day after it opened up. And within a week or two I was at Theresa’s, the legendary South Side club at 48th and Indiana. I met Junior Wells and Sammy Lawhorn and so many other great people there. That was kind of my entree in Chicago, and everything grew from there. In a way I also owe it all to Eddie Shaw.

How long did it take you to write Chicago Blues: Portraits And Stories?

The first three books included some revisitations or revisions of articles I had done previously, but many of the chapters were also new. So maybe a year or year and a half; I don’t really know, as it has been a few years. Transcribing interviews takes time. It’s a three-to-one ratio; for every hour of an interview, there’s three hours of transcribing done. But I was fortunate. I got to know people like Sunnyland Slim, Big Walter Horton, and Junior Wells, who was born in 1934, by the way, not 1931 as it says in the book– that’s a typo that somehow got past me, which I still kick myself for every time I see it. I was also lucky enough to be able to interview Billy Branch, Sharon Lewis, Lurrie Bell, and the other people I did first person profiles with, right here in Chicago. I was fortunate enough to have them living close by.

Southern Soul-Blues was a little more involved because a lot of those artists lived in the South. I either interviewed them when they came through Chicago, or by phone – sometimes, both. Then Denise LaSalle actually called me after reading her chapter in Southern Soul-Blues. She said, “I like your writing! I’d like you to work with me on my life story.” I was very honored, of course. I started going back and forth to Jackson, Tennessee, where she lived; that’s how we did that one. Blues Legacy, which came out just before Denise’s book, was basically an update of Portraits and Stories – the music is still here, it’s still growing, a lot of the old masters are still around and there are exciting new faces on the scene.

Several people – James Cotton, Eddie Shaw, Eddy Clearwater – actually passed away between the time I spoke with them and when the book was released in 2019. Floyd Taylor, whom I originally had intended to include in Southern Soul-Blues, passed in 2014. That’s how urgent it is that these stories get told, and these legacies get honored, while there’s still time.

What is your writing process like?

I have always liked doing interviews, and I have always encouraged people to tell their stories. My first inspiration was Peter Guralnick. I am not putting myself in his league because he is an absolute master, but in Lost Highway and Feel Like Going Home, he devotes one chapter to each artist, and through the course of the chapters, the music and its history come alive. He was my first inspiration.

I’m not saying I’m the second coming of Peter Guralnick, because I’m not – he is the master! Also, Stanley Booth is another eloquent writer. He’s done similar things in books like Rhythm Oil – profiles of artists and descriptions of performance venues to illustrate the lived reality of a certain scene and a living cultural history.

Can you talk about your friendship with Sunnyland Slim?

We were friends. He had much closer friends in terms of people who really shared life with him, musicians like Sam Burckhardt, the sax player; Sam was like a godson or grandson to him. But I admired Sunnyland so much for his wisdom and his power. Being around Sunnyland was like being around Buddha.

He had this incredible way of living and speaking, a really profound wisdom you could absorb just by being in his presence; he’d come up with these deep aphorisms he’d just pull out of everyday life and lay on you. Just being around him was inspiring because he was such a powerful presence and such a powerful spirit. Like with so many of these artists, it was one of the great blessings of my life to be able to call him a friend.

What influence did Junior Wells have on you?

Well, I never knew Junior really well until the end. He didn’t like writers. He didn’t trust writers. That was part of the reason he didn’t really trust me, but then I became very good friends with a friend of his. She and I became close friends. Through that, he began to trust me because he cared a very great deal about her, too. She was in very ill health, and we both did what we could to take care of her financially and whatever else was needed.

When he saw that I truly cared about her, he opened up to me. We became closer toward the end. He had a good heart. He had that kind of streetsy, hard-nosed strut about him and he could put on an attitude when he wanted to, but he had a real good heart. I saw him almost in tears at times thinking about people he cared about and loved. He was another very deep cat. You had to get next to him to see that side of him. I’m still hoping he’s forgiven me for that typo in the book about when he was born!

You are also a writer at The Chicago Reader. How do you like it there?

These days I am mostly doing Critics’ Choices. They haven’t had music features for a while; they’ve cut back. But in earlier years, I had the opportunity to write some pretty good articles. The Sunnyland Slim chapter in Portraits And Stories, the Bonnie Lee chapter, the chapters on Maxwell Street and the Delta Fish Market, parts of the Junior Wells chapter – those arose from pieces I had done for the Reader. I was also doing live blues reviews for a while, but I haven’t done any of those for a long time. As I said, they’ve cut back on their music coverage. These days it’s mostly Critics’ Choices or previews for upcoming shows.

These can be mini stories within themselves. I did a preview on Melody Angel, the guitarist who’s also on the cover of Blues Legacy, which included some background information as well as a little portrait of her as an artist; a year or two ago, there was a reopening of a very well-known South Side club called The Odyssey. I got to talk about the club as well as Joe Pratt & The Source One Band who were playing there. And along with Bill Dahl, one of Chicago’s finest blues and roots-soul/R&B writers, I’ve been doing previews of the Chicago Blues Festival for the Reader for quite a few years. These days, though, it’s mostly previews of upcoming shows.

Out of all your published books you’ve written, do you have a favorite?

That’s a hard one to answer they’re different from each other. With the first Chicago book, Portraits and Stories, I was grateful I had the chance to recognize some important Chicago artists while they were still active and also pay tribute to past maters like Sunnyland, Junior, and Big Walter. That was certainly a great privilege. With Blues Legacy, the second Chicago book, I was grateful for the opportunity to recognize some earlier-generation figures, like Cotton and Eddie Shaw, whom I hadn’t included in Portraits and Stories, and again showcase some of the younger artists who are still maybe a little below the radar. We have artists like Jamiah Rogers and Melody Angel. Jamiah is in his twenties and Melody is a little older than that. Then there are older musicians like Billy Boy Arnold who are still carrying it on. And as I said, I was able to give recognition to legends like Cotton, Clearwater, and Eddie Shaw, although of course I’m sorry they didn’t live long enough to see it.

With Southern Soul-Blues, I was happy to spread the word about the modern genre that unfortunately too many people outside the South don’t know about. People like Sweet Angel, Ms. Jody, Sir Charles Jones, and TK Soul aren’t really well known outside the southern circuit. I was grateful to do that, and to emphasize that is also carrying on a tradition, the soul music tradition as well as the blues.

Denise LaSalle, as I said, called me after reading her chapter in Southern Soul-Blues and asked me to work with her on her autobiography. I was very touched and very grateful that she wanted me to do that. As it turned out, there were a few things I wasn’t able to double-check with her, because she died in January of 2018, when I was still working on the manuscript. Turns out there were a few memory issues I had to correct. I actually have a little note that I inserted at the beginning of the book. The club she identified as The High Chaparral was actually The Burning Spear. It was owned by Pervis Spann and E. Rodney Jones of WVON, Chicago’s legendary Black radio station. She mistakenly misidentified it when she saw the photo of her performing there. By the time the proofs came out, she was gone, so I couldn’t double check that with her. I later discovered, by accident, pictures from The Burning Spear, and I recognized the club immediately. I corrected that in the note I inserted, and I also corrected the spelling of one of the names in the book.

But she told me her life story, she was honest and direct, and I was very gratified that she trusted me and was willing to do that. And in the process, she became one of the dearest most precious people in my life; it was a privilege and a blessing to help her get her story out, and even more so to grow to cherish and love her as a friend. Her daughter Bridgette and I are still good friends. We are like brother and sister. We have ideas to carry on her legacy, too; we’re still working on that.

Can you talk about contemporary blues musicians?

I respect them all. People like Jamiah Rogers and Melody Angel are exciting younger artists. They are combining the blues with more contemporary influences. I give Melody a special nod for her topical lyrics. She’s a blues singer, and she can sing about partying, dancing, and having a good time like anyone else – her Hendrix tributes are always a highlight – but she also addresses crucial issues of the day from the perspective of a young, socially aware Black woman. Her honesty is uncompromising – really, like hip-hop put to blues – and I respect that highly. I hope we have more artists doing that in the future.

Since the book was written, there are more artists coming up who are starting to make an impression. Basically, all I can tell people is what I said in the book: Get out there and hear the music. If it’s someone you’ve never heard of, still make sure you get out there and hear them, because you’ll probably find something that will delight and excite you. You’ll probably find something you’ll want to see and hear again.

What’s next for you and is there still a dream book you would like to write?

Well, there are a couple of autobiographies I would like to work with people on, but they’re just too far away. Part of this process is being in person. You can do it by phone or on Zoom, but I can tell you for sure that with Denise LaSalle, for instance, some of the best things in the book weren’t from formal interviews. We were just hanging out, having coffee or driving around Jackson, Tennessee seeing the sights, or having breakfast together at the Waffle House. I always had my little hand-held digital recorder going, and she would just be there talking about life, or she’d see something or hear something, and – “Oh. yes, that reminds me . . .!” That doesn’t happen in a formal sit-down interview, on Zoom or anything else. That’s just hanging out with someone. That’s in-person. You just can’t do that otherwise.

Latimore has said he might like to work with me, and I’d love for that to happen. Lat is just like Denise; he’s a very personable and warm man, and being with him is a wonderful, open experience. I always enjoy talking with him. He’s an important artist with a great story to tell, but he’s in Florida – I can’t keep going back and forth to Florida. I also heard that Mable John was looking for someone to work with before she passed away. I would have loved to do that, also, but she lived in California.

The great Jazz singer Sheila Jordan has never done an autobiography. She’s living in upstate New York now, and she’s ninety-three years old. She’s one of the few Jazz artists who is still alive who worked with Charlie Parker. She’s an amazing artist who crafted her style from Bebop, Native American chants, and other sources, both traditional and modern. And again, she’s very warm and personable, a delight to talk with. Just to talk with her about how she developed her vocal style would be incredibly deep and valuable. She’s also had a very eventful life. She lived the “Jazz life,” as they called it then, with all the pitfalls and downfalls that implies, and she survived it. She’s always been up front about her experiences and what she went through. She is an amazing woman and is still singing. Once again, though, she’s halfway across the country. I have no idea how I could do that, but I would love to.

Any final thoughts on Blues music?

Anyone can play the blues, but I always insist that Blues is Black music. I still insist on that. Anyone can love it, but its roots are in the African-American experience and the African-American legacy. I think that has to be emphasized, and that has to be the focus. Whoever is playing the blues is playing Black music. The extent to which they honor and feel this determines if the music is going to come out right. Someone like Dr. John knew it from his heart.

Most of the Black musicians who worked with Stevie Ray Vaughan had deep respect for him because he respected them, the music, and where it came from. And someone like Sheila Jordan, of course, brings the same depth of understanding and knowledge to Jazz, another art form that has arisen from the African-American cultural legacy. But the root of this music is in the American Black experience, and I think this is what has to be respected and acknowledged.