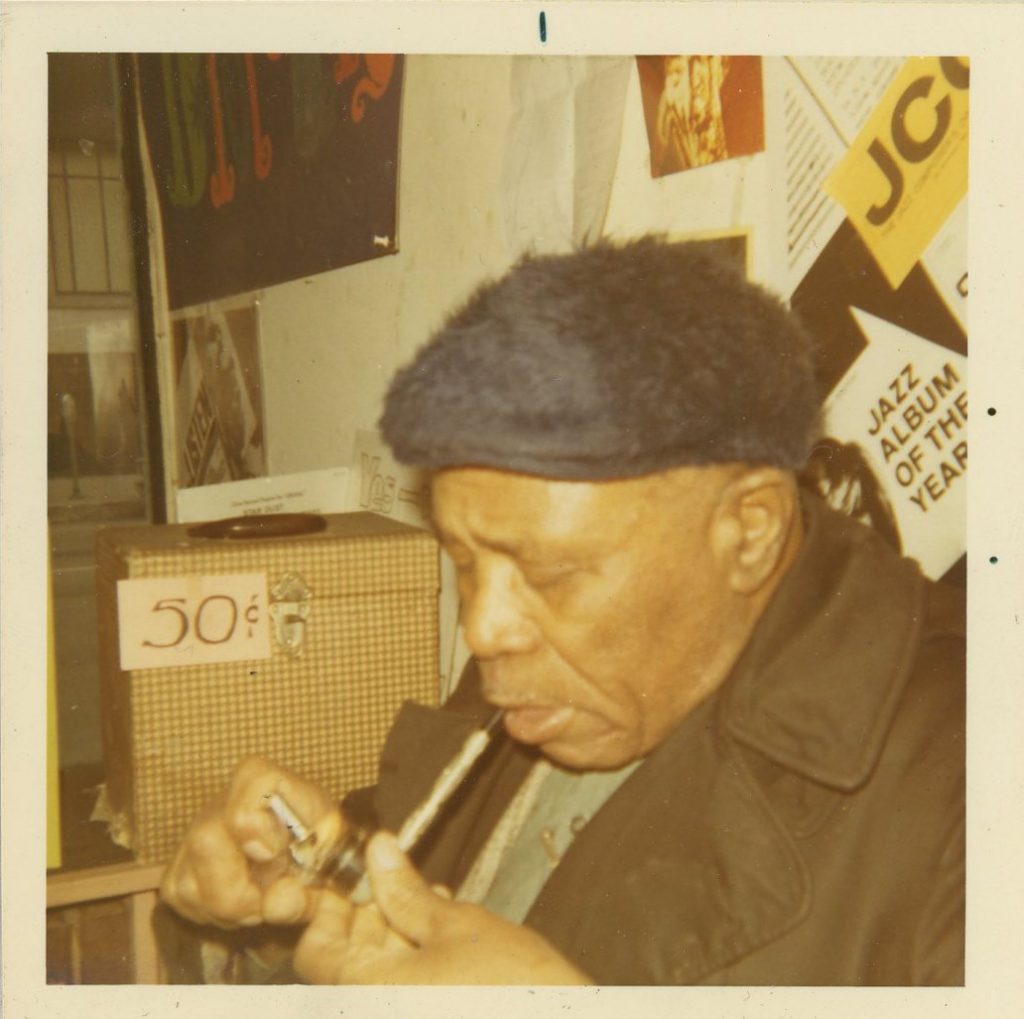

Bob Koester, founder of Delmark Records and Chicago’s Jazz Record Mart. Both were based at 7 W. Grand Ave., right at the Grand Ave. subway stop, during the time I went there a few times per month during the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Koester patiently took time to answer my questions about blues and jazz and the record biz, and I gleaned much insight about life and society in our many conversations.

The Wichita, Kansas native, born October 30, 1932, was a record collector from his teenage years on. He studied business and film at St. Louis University. He launched the Blue Note Record Shop in St. Louis in partnership with a fellow collector. The partnership dissolved and Koester founded Delmar Records, named after a St. Louis street. Initial album releases were by Speckled Red and Big Joe Williams. In 1958, Bob relocated to Chicago and acquired Seymour’s Record Mart, which over time became the Jazz Record Mart. Delmar became Delmark (adding Koester’s initial) due to potential trademark infringements, and became a major force in the audio preservation of both traditional and contemporary blues and jazz. The store moved four times, its inventory eventually acquired by Wolfgang’s Vault. In 2018, Delmark Records was sold to Julia A. Miller and Elbio Barilari. Koester died on May 12, 2021 while in hospice care from complications of a stroke.

Delmark was well known both as a force in blues recording (some of the idiom’s most essential albums of all by artists like Junior Wells, Magic Sam, J.B. Hutto, Sleepy John Estes, Roosevelt Sykes and Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup) as well as jazz of all eras – including an authoritative cross section of experimental jazz from Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). When I spoke with him, Bob was still frequenting the city’s South Side and West Side blues bars, and showed movies at the store every weekend.

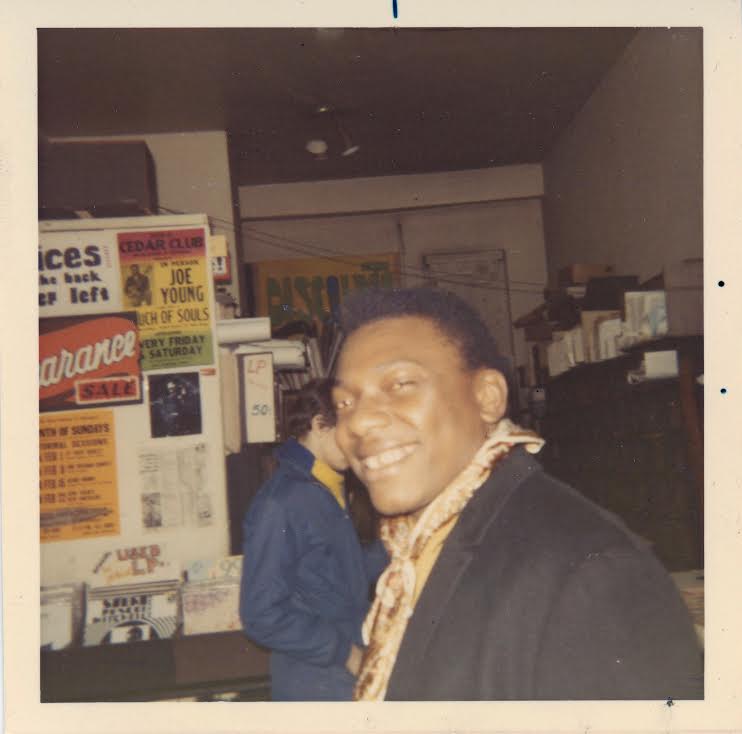

I used to frequent the Jazz Record Mart every possible Saturday. I’d ride the El train down from the north suburbs to where it became the subway beneath Grand & State. Sometimes I was the first customer in the store that day; I remember waiting for the store to open with New York avant-garde composer Moondog – in full Viking regalia – waiting to get in. I also met such blues legends as Big Joe Williams, Sunnyland Slim, Carey Bell and Jimmy Dawkins, all hanging out and talking with Koester.

Disclosure: This conversation was not recorded. Rather I took notes – in my own style of shorthand on a legal notepad. Remembering Koester’s distinct diction, even after 40 years, I have done my best to flesh out my scribbles with the best possible degree of authenticity. But they don’t (and can’t) capture the exact syntax intact. My apologies for any liberties or errors. Nonetheless, in honor of his outsize legacy, I felt this lost conversation on a variety of topics – biographical and occasionally personal and even random – was worth transcribing and preserving to the best of one’s ability to do half a century later.

On Wichita and family: “I grew up in Wichita, a cultural cipher. My family was of a Catholic background, Republican. My dad was a geologist. I was working to be a cameraman. I had two brothers: One is with Universal and worked on (the 1973 film) Jonathan Livingston Seagull. The other one’s more creative – features to porn.”

Early jazz interest and surviving polio: “I became interested in jazz upon hearing Fats Waller and Eddie Condon during the time I had polio in 6th grade. Everybody (had it) in those days, and there wasn’t much they could do about it – this was before the Salk vaccine – so they’d throw you in the hospital and wrap your affected parts of you in hot water…Polio was more fun than the cure, which made me sick to my stomach and gave me headaches. My legs…one is smaller than the other. My mother called all my friends together – and I didn’t have many, being Bob Koester – to tell them that I’d be limping but not to say anything. I don’t limp. But my mother may still be calling my friends saying, ‘Bob limps, but don’t say anything!’”

High school and college: “I got more into jazz. I was going to go into math or tech if I didn’t become a filmmaker or cameraman or direct or produce. I was always kind of a producer. After a film career I was going to retire and open a record store and maybe a small record company….I was going to go to UCLA film school as part of my post-grad program at St. Louis University. My folks decreed that I would go to Jesuit college like Loyola in Chicago or New Orleansbut I wisely decided against it as I’d become involved in the St. Louis jazz scene. There was a Dixieland band playing a block from campus. There was a bop joint about three blocks away, across from a tavern owned by a guy named Charles Thompson who won the 1916 Ragtime Piano Contest. Tab Smith, who did ‘Hurricane,’ played two blocks from campus.So it was very wise to stay in St. Louis because if I had gone to New Orleans or Chicago for college, I’m sure I’d be in the record biz instead of the great filmmaker I’ve become!” (Laughs)

Record collecting and roots of retail: “I became a collector of 1930s pop. I had batches of records. My dorm room looked like a secondhand store. I ran some mail order. I wanted a regular record store. Eventually I noticed a tiny store at Laclede & Grant. I stayed there through college, then moved to Delmar and DeBaliviere. I still liked St. Louis but became a little depressed. All my favorite restaurants were gone!”

Origins of the label: “I began the label while still on Laclede – it’s Laclede Village, low-rise housing now. The east wall of the record store was the western boundary of the Black ghetto. There were the Pruitt Homes over by Biddle Street, a famous Black street. So I got up every morning – sometimes I slept only 15 minutes, woke up and got into the habit of catching up with my sleep between classes…I’m such a night person anyway that I spent my nights spread over separate (recording) sessions…My main motivation was to get the money I needed for the label. It didn’t take much to call a blues or jazz record a success. Just do better than the one before it. Blues did better than jazz.”

Scufflin’: “I was really scufflin’ in St. Louis, shopping at second-hand stores. Most of my capitalization went toward buying good 78 collections. We – that’s the “editorial we” – got an allowance from Dad. I spent it all on records, and I worked at Garavelli’s Cafeteria. I didn’t have to worry about food – dad paid for that. Then my standard of living declined when my allowance went from $200 per month to $75 per month. Call it payola to keep me focused on college”

Roots of Jazz Series (Delmark’s blues series is called the “Roots of Jazz Series”): “That’s what I think [blues] are; jazz is rooted in gospel and blues. It’s not impossible that we’d get into gospel. Lots of jazz people don’t recognize blues. Hell, polka is part of jazz in Minnesota where they use polka to flesh out the Dixieland bands. Anything in the air is part of the roots of jazz, but blues played a significant part.”

Chicago-bound: “I moved [to Chicago] with the help of John Steiner. He had a label called Steiner-Davis (SD) Records and recorded Red Norvo, Baby Dodds, etc. And in 1949, he bought the old Paramount label from Grafton, Wis. Including the Black Swan label. He had Riverside Records also, although not doing anything with it. He was going to sell me the record company. I had capitalized myself a little bit. I bought a car to move here, with two one-way trailer rentals that held everything I needed: Lots of records and empty jackets…Til I bought a folding bed from Erwin Helfer, I used to sleep on cartons of of LP jackets with some blankets.

“I did that for two or three months at Wabash & Chicago Ave…42 E. Chicago Ave… I was selling 78s for John Steiner on commission. Found two good 78 collections. I never even painted a window sign, It was my apartment/commercial live/work location, that I got for $125 – a hell of a lot of money for that real estate. Then I learned that Seymour Schwartz’s Record Mart on S. Wabash Ave. wanted to sell. I got a call from Seymour Schwartz. He came to my apartment and told me he wanted to sell the day before I was going to offer. He’d started in the biz on a pushcart on Maxwell Street. I paid him $1,500. I bought it in March 1959. We moved to 7 W. Grand Ave. in September 1963. And the rest is history.”

Joe Segal (future promoter at Chicago’s Jazz Showcase) and Erwin Helfer (blues pianist): “Joe Segal worked at a jewelry store. He came to work (for us) and hasn’t missed a meal since then. He brought Ira Sullivan and the John Young Trio. Come that fall, I remember, there was a steel strikeand a lot of South Side customers disappeared. I had to pay the bills on those damn records…Erwin Helfer was a Tulane student. He came through town and recorded Speckled Red. Later, he bought a Crown tape recorder; I don’t think they make them anymore. Professional tape recorder, but not too gentle with the tape. I was making $5/$10/$25 payments. There’s not a lot of point in marketing deceased artists [like Speckled Red] – you can’t really help them.”

Chicago nightlife: “I spent time in Chicago learning the scene. I’d get on the subway and go see (trombonist) George Brunies out by Bryn Mawr, and Art Hodes played two blocks away at Thorndale & Broadway. Little Brother Montgomery would be playing the Hollywood Show Lounge, a quasi-cocktail bar. He was working with Otis Rush – trumpet, tenor, baritone saxes and Little Brother on piano. This was my first experience with post-Muddy Waters urban blues. I always wanted to record Otis but knew he was beyond reach. I hadn’t yet issued [Speckled] Red or [Big] Joe [Williams]. I used to see Muddy at Smitty’s Corner with James Cotton on harmonica, and he told me about a new guy, Mighty Joe Young, who was playing the Green Door on 63rd Street with Billy Boy Arnold, who borrowed (licks from) all John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson 78s. He’d already recorded for Vee-Jay, I think.”

Chicago’s Record Row: “Basically I was unaware when I came to Chicago that most of the ‘50s blues labels were out of business already. I do remember being driven around, seeing United Distributors, which had moved from Cottage Grove to S. Michigan Ave.’s Record Row. When we’d issue 12” LPs, we were amazed by the response from James H. Martin, who was the strongest distributor in the region. MS Distributors wasn’t interested. So we went with Allstate Distributors when Hy Frumkin who sold to Paul Glass.”

The Folk Revival: “Folk was enormous – as big as rock, with many of the same people. I went to Europe with Sleepy John Estes. Artists like Dave Van Ronk, John Hammond and Eric Von Schmidt – the white singers – are selling numbers like tens of thousands of records.”

Charlie Musselwhite: “Charlie came into the store one day. I walked upstairs from the basement and here’s this guy who looked like an old wandering orphan with a guitar on his back. Charlie came to work for us, shipping records for not much money but I had a good deal on a four-room apartment on Grand so I gave him the back bedroom for $25-$50 a week.”

Pete Welding, Paul Butterfield, Mike Bloomfield: “Pete Welding is great producer and liner note writer and I distributed his Testament Records label for a while. But we split horribly over Junior Wells. He gave Hoodoo Man Blues two stars (in Downbeat). It was the beginning of the end of a beautiful friendship. Pete thought he was a mugging pimp or something (laughs). We also argued over the validity of a lot of white artists. I was never down on Butterfield, other than that he wasn’t a very pleasant person I never had that much to do with him nor Elvin Bishop. Mike Bloomfield did publishing work her for $10 a week, and appeared on two different LPs before 1962 while going to Roosevelt University….Welding did tell me I needed to sign Roscoe Mitchell, and then gave Roscoe’s album five stars in Downbeat!)”

The Grateful Dead: “The Grateful Dead recorded Junior Wells’ [arrangement of the John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson song] “Good Morning Schoolgirl.” I guess [Lester] Melrose had the publishing. But the [Dead] record was a note-for-note ripoff from Junior’s Hoodoo Man Blues. Junior sang it like Howlin’ Wolf would have sung it. It wasn’t just circumstantial. I have a lot of respect for the Dead – one of the few rock bands I really dig. I hadn’t cared for Jefferson Airplane for some reason. But I like that psychedelic, erotic shit partly because I had seen a movie at [Old Town Chicago’s] Aardvark Cinema called The Grateful Dead. Beautiful. And I liked the music so much, I stocked it [in his otherwise jazz- and blues-oriented store which sold few rock releases].I never felt that I had been screwed. But they ought to give an arrangement credit to Junior Wells!”

Magic Sam: “Originally I didn’t realize how good he was!”

Bruce Iglauer, founder of Alligator Records (and former Delmark employee): “Bruce had been the recipient of Delmark promo copies while at student radio (at University of Wisconsin) who said: ‘I want to come to Chicago, start a blues magazine and a blues record company.’ He was frank and straightforward. He wasn’t here too long before he became interested in Hound Dog Taylor. I’d heard Hound Dog, of course, and had never heard him finish a tune! He’d be drunk and his big, long hands would go over his face, and I thought Bruce was crazy [for liking him]. But I would have taken his word and believed in his knowledge I remember he begged and pleaded – we must record Hound Dog Taylor! At the time I really wasn’t signing anyone – I was trying to buy the building at 4243 [N. Lincoln Ave.] and had to delete four titles to do so….[He talked about employees Ray Townley, Steve Tomashefsky and AACM proponent Chuck Nessa.] I sort of have a saying that I don’t respect anyone who works for me for ten years! (laughs)”

About the author: Cary Baker is the retired founder of Conqueroo, a leading roots music publicity company named after a lyric in Dixon’s “Hoochie Coochie Man.” A Chicago native, Baker wrote for publications like Chicago Reader, Creem, Billboard, Record, Bomp!, Trouser Press, Goldmine, Hit Parader, Mix, Illinois Entertainer, Living Blues, and more. He worked as head of publicity at Capitol Records, I.R.S. Records, Enigma, Morgan Creek, Discovery and Ovation Records. Upon retirement, Baker is at work on two books and a reissue project. You can also read his May 13, 2021 tribute piece to Bob Koester here.