“I’m a transformative artist,” Danny Kalb told me in 2009. “Just like Dylan or Muddy Waters when he heard Robert Johnson, and he integrated it, but he wasn’t defined by it. Charlie Parker heard jazz in the ’30s and turned it into a different kind of music.”

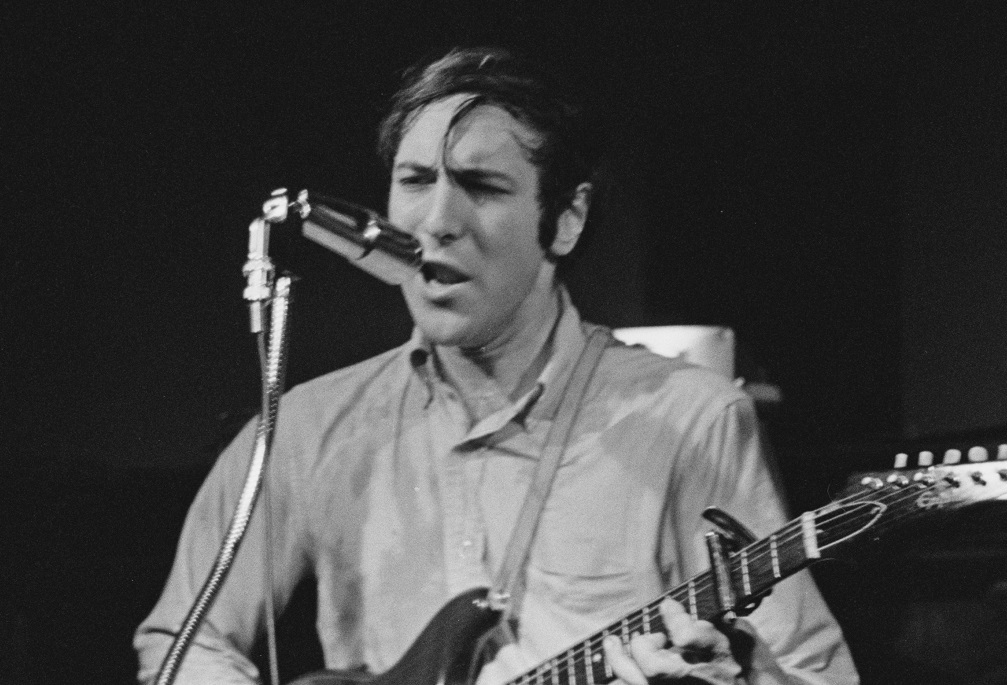

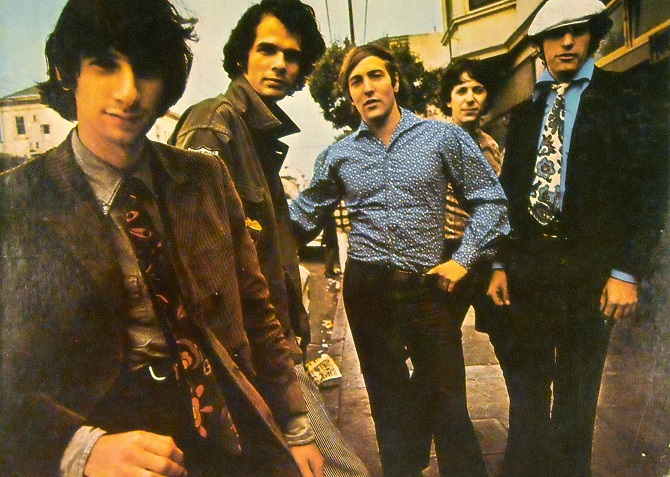

Danny passed away on November 19th. He was the founder, lead guitarist, sometimes singer, and songwriter of The Blues Project, a group that in 1965 promised to change the very paradigm of roots music only to fall apart as each member went their separate ways.

Ironically, The Blues Project’s crowning moments were their public debut at New York’s Café Au Go Go where they were for all intents and purposes the house band captured on their debut album Live at The Café Au Go Go in 1966. From that moment on, it was a slow down hill slide of missed potential. That said, Danny remained a spectacularly innovative guitarist for the next half century. He became my personal friend in 2006. These quotes come from formal interviews I did with him in 2007 and 2009.

Danny Kalb was a catalyst of creativity whose impact on artists he worked with has been overlooked. He played with people like Dave Van Ronk, Rev. Gary Davis, Eric Von Schmidt, Spider John Koerner and Tim Hardin. He also recorded and/or played with Pete Seeger, Judy Collins, Jimmy Witherspoon, Phil Ochs, Geoff Muldaur, Eric Von Schmidt, and Artie Traum. Andy Kulberg, Roy Blumenfeld, Al Kooper, and Steve Katz were his band mates in The Blues Project. “Jerry Garcia and Jorma (Kaukonen) used to come down and watch me and Mike Bloomfield play.”

The Mayor of MacDougal Street, Dave Van Ronk, was Danny’s mentor. Van Ronk was singularly influential in precipitating “The folk scare” as he called it in Greenwich Village in the late ’50s. “Dave was on my side,” Danny told me. “He always liked my music, and he always gave me his thumbs up. He’s basically the reason I’m a professional musician today. He was God to me.”

Danny identified with Van Ronk as a kindred soul, a musician’s musician. “There’s this deep mythologizing of Dave and not seeing how great he was,” said Danny. “You have to tell the truth about people.”

Van Ronk’s seminal guitar work was a jumping off point for Danny although he didn’t see himself that way. “I don’t think about it. I just love what I love. Love rules! Love is everything, like the Beatles said. When it came to Gary Davis, it was an explosion of joy when I first heard him. For me when I heard Muddy Waters, when I heard Robert Pete Williams, when I heard Brownie McGee for the first time with Sonny Terry, it was an explosion of joy in my soul, and I knew I had to go into that and find something there that I could do in my own way.”

I watched Danny struggle with the demons of self-doubt and depression as he worked diligently to break out of his decades-old cocoon like a butterfly and take the promise of The Blues Project to a level of influence equal to the other great guitarists that he worked with.

“I used to go to what Bob Dylan calls the persecutor within as a reflex.”

In other words, Danny struggled to get beyond his own self-doubts about his talent. In 2009 he still questioned the reality of his unrealized potential in trying to reach the masses with the kind impact Dylan had. “Now, I think of it as the devil, and the other side of what I believe to be the basic nature of the universe.”

Danny hung out with Dylan when he was still Robert Allen Zimmerman from Minnesota. Danny first performed with him at a Riverside Church folk concert in 1961. He was painfully aware of Dylan’s impact on humanity and how Dylan’s commercial success transcended the ripple effect of Van Ronk’s impact way beyond that of the Greenwich Village scene of the early to mid-60s.

It was Dylan who told his minions that there was something blowing in the wind, and that we didn’t know exactly what it was. The Blues Project promised to be the soundtrack of that generation, the link between both Delta/Chicago blues and rock and roll that Elvis telegraphed when he recorded Arthur Big Boy Crudup’s “That’s Alright Now Mama” in 1954. That link was more clearly defined when Dylan went electric with The Band. The link that the Stones, the Animals and The Yardbirds drove home in the British Invasion. Johnny Winter in Texas, The Grateful Dead in San Francisco, and Duane Allman in Georgia were introducing electric blues to a mass audience.

The Blues Project did the same thing in New York, but personnel issues and a label that had no idea of their potential squashed what should have been an explosive mass acceptance equal to the other artists mentioned above putting The Big Apple in the same bag as innovators in a sound that had come far from its origins on the banks of the Mississippi.

“I never felt like I wanted to imitate. To imitate is to die. To embrace, to make love to the sound and the meaning of the sound, that’s the key. Not just the sound, the style alone, but the actual meaning of it which was helped by my background as a left-wing kid and the civil rights movement which was on the agenda at the same time I was listening to largely black artists.

“Though Dave (Van Ronk) was not a black artist, he was a combination artist the same as Elvis. It was the American thing, and America was changing. It was a time of great changes in America, and so all of us felt a sense of fresh, beautiful newness of a country that could change and was changing itself. It was the civil rights movement.”

Danny was a loner when I met him. Frankly, I idolized him. And that adulation was something he needed. Affirmation from an artistic genius like Danny was something I needed, too. “I think you’ve always been a good friend to my art as well as to me as a person,” he told me. “And I think it’s very important to have certain people like yourself, like Sean Williams, the professor of history at Princeton, like Dave Van Ronk in my early years when Dave gave me thumbs up, like Odetta who gave me a thumbs up.

“It’s like people who gave you a thumbs up during certain periods of your life, early or late. They’re invaluable because that gives you the good feeling that you have something to do which I think I’ve always known in my life, but sometimes you forget during times of testiness, and also it’s good to feel good that you’re affecting people’s lives with your music. That’s the meaning of it.”

To me as a journalist, it’s fulfilling to bring incredible geniuses into focus at a time when little is being written about them as people rather than as product. Danny was real. Like all of us, he had flaws, flaws that kept him from enjoying the level of success he deserved. But when my mother died, he came up from Brooklyn on the train to mourn with me. You can’t define that kind of friendship in terms of “success” by any other measure. As my friend, he was an almost unimaginable success.

Now into his second half century as the warrior music journalist, Don Wilcock began his career writing “Sounds from The World” in Vietnam, a weekly reader’s digest of pop music news for grunts in the field for the then largest official Army newspaper in the world, The Army Reporter.

He’s edited BluesWax, FolkWax, The King Biscuit Times, Elmore Magazine, and also BluesPrint as founder of the Northeast Blues Society. Internationally, he’s written for The Blues Foundation’s Blues Music Awards program, Blues Matters and Blues World. He wrote the definitive Buddy Guy biography Damn Right I’ve Got The Blues, and is currently writing copy for a coffee table book of watercolor paintings of blues artists by Clint Herring.