“We really didn’t know what we were doing except for what we wanted to do,” says Steve Katz looking back at the original Blues Project in 1965. “The whole thing was that we were nuts. We were like five nutty Jews, you know what I mean? We were just bouncing off the walls, and it was perfect because the Café Au Go Go wall was only three feet from the stage, and we were basically bouncing off their brick wall.”

The original Blues Project’s first album Live at Café Au Go Go promised to put The Big Apple on the map with San Francisco and London as a center of a worldwide burgeoning music scene. The late great guitarist Danny Kalb was the leader of that band. You can read my homage to him elsewhere in American Blues Scene.

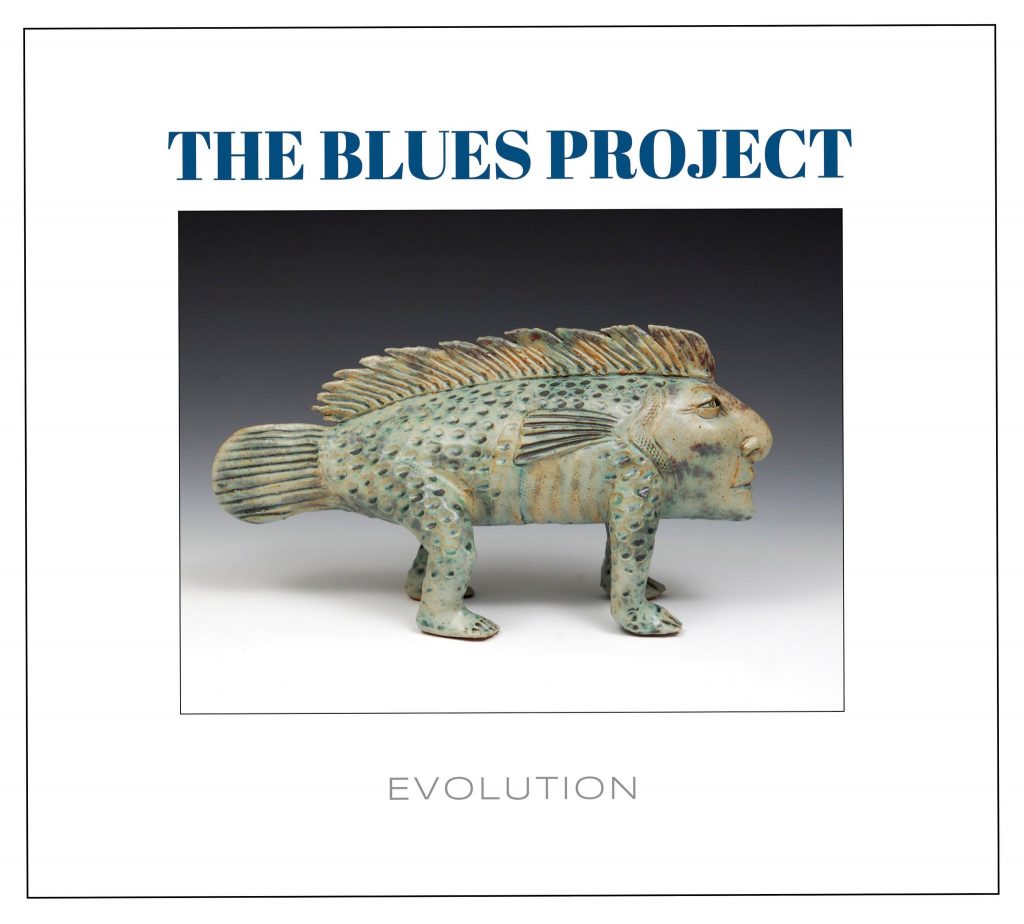

Fifty-seven years later, Katz and drummer Roy Blumenfeld from the original band have put The Blues Project back together. Their album Evolution miraculously captures the magic of the original group which never rose to the attention it deserved. “I’m just so happy that at my age I’m involved in something this good,” says Katz. To understand the significance of this second chance at the brass ring, it’s important to put The Blues Project in historical context.

The British invasion by 1965 had become a wakeup call to American rock musicians. The old paradigms were out the window. Record labels no longer were calling the shots. The suits weren’t signing individual artists. Groups were making the hits. They were writing their own material and controlling their own studio releases. Music was less about business and more about heart and soul.

Rock and roll had been born a decade earlier, exploding out of the collision of blues and country. Young girls were the core market. They hung photos of teen idols on their bedroom walls and bought 45s, singles they played on portable record players.

The Beatles opened the floodgates for these groups. Their success and the flood of others like The Stones, The Animals, Cream, and Yardbirds woke up young American musicians to a brave new world of possibilities. Haight Ashbury in San Francisco in 1965 brought the pop music focus back to America. The Grateful Dead, The Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service and other West Coast groups expanded the pop music market from teenyboppers to the college crowd already listening to folk, jazz, and the Brits.

“Underground” rock offered the theme songs for this slightly older generation. A whole new youth culture emerged. These groups were drawing inspiration from a plethora of sources including folk music from around the world, jazz, rhythm and blues, and indigenous regional sounds being played on stereo FM radio stations that offered an alternative to top 40 AM.

It was into this milieu that The Blues Project was born. The members of this band had been part of the Greenwich Village folk revival. As a college student at the time, I saw them as a possible East Coast vanguard, front runners in the exploding alternative rock movement around the globe. If England had the Stones, San Francisco had The Dead, and Boston had The Beacon Street Union and Ultimate Spinach. The Big Apple had The Blues Project. They did a lot of things right musically, but the things they did wrong have left them as little more than a footnote in musical history.

While blues was in their name and blues was part of their game, the music they created was as eclectic as the Grateful Dead’s. Plus, it had just enough jazz influence to make their sound totally their own.

“I think we all wanted to do a little bit of jazz. I didn’t think about what direction we went in. I was having too good a time. Hey, you wanna play jazz? Sure, let’s play jazz. Let’s do ‘Flute Thing.’ Ok, I’ll play bass. The beautiful thing about The Blues Project was that every performance was different. We improvised so much. That it was never caught on an album is really a shame.”

They had set lists for every performance. “Yeah, we did, not that we abided by it. There were times when a mic didn’t work or something broke on stage. I’d walk up to the microphone and sing ‘Misty,’ and I would look ridiculous, and everybody would be cracking up. But it was fun. It was fun like that. I can’t imagine Jerry Garcia singing ‘The Lady Is a Tramp’ right into the middle of one of their sets. I used to do that kind of shit. So did Zappa. Zappa was incredible. You can’t even talk to me about the Grateful Dead in the same sentence.”

The wrong record label and explosive personnel issues sabotaged the original group. Columbia Records turned them down flat. That huge conglomerate may have been prescient in signing Dylan, but they had a corporate mentality that was a decade behind the times in 1965. This was a company that signed Dion because they felt as an Italian they could groom him for playing the Copa Cabana. Elektra, on the other hand, would have been a great choice, and the label wanted them, but Katz blames the group’s manager for blowing that deal.

“Why did we sign with Verve Folkways? It was really MGM, and they brought us out to their convention and all of that stuff, but we left it up to our manager who was awful before we went with Syd Bernstein. Syd was very good, but it was Danny’s friend Jeff Case who was managing us, and he was a guy who ended up stealing my royalties from ‘Steve’s Song.’

“He said he wrote it, and they kept sending him the checks for years until we found out who it was. Yup. So, that’s how we wound up – who knows what kind of deal he made. He was a real schmuck, and he probably ended up taking money under the table.”

The Blues Project also had personnel problems. Tommy Flanders, the original vocalist on Live at The Café Au Go Go, left early on. “He stayed in L.A. He wound up in one of those Jack Nicholson teenage exploitation movies. He was like a co-star, which was perfect for him. I mean he just didn’t fit in with the rest of us, but the problem was there was no great singer. Kooper tried, and so did Danny.”

Danny Kalb was the leader of the band. His unusual guitar style put the band in a category of its own, but his drug issues precipitated his jumping out of a six-story building. It didn’t kill him, but let’s just say it made creative decisions with others in the band problematic.

Keyboardist and occasional vocalist Al Kooper left the group shortly after they played the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967. Both Kooper and Katz would eventually end up in Blood, Sweat and Tears. That, too, was not an easy transition.

“We weren’t talking when he left The Blues Project. I was really pissed off at him for doing that. We made up and said let’s do something together ’cause I was leaving also. The problem was that Kooper wanted to put horns into The Blues Project, but it was Danny’s band. Danny hated the idea of putting horns in, but then I left because I wanted to move on to something different.

“I was putting my own stuff together with (drummer Bob) Colomby. Then I got a call from Al to play behind him. This was like two months after Monterey, and he says, ‘I want to start my career fresh again in England, and I want to do a benefit at Café Au Go Go. Will you and your friend Bobby (Colomby) back me up, and my friend (BS&T bass player) Jimmy Fielder at the Café Au Go Go for this benefit concert?’ I said sure. He wanted to raise enough money to get to England.

So, we did the benefit. Nobody shows up, but he raised enough money to get a cab to the airport. We played at the Café Au Go Go. Then, we played The Scene, but our first bigger concert – I think it was opening for James Cotton at the Village Theater.

“I said, ‘Bobby, let’s see what the marquee looks like and see what our name looks like,’ and we drive up to the Village Theater, and it says Al Kooper’s Blood, Sweat and Tears. I flipped out. I just flipped out. I ran in, and I started screaming at – he probably thought I was a total asshole. “I said, ‘This is not Al Kooper’s band!’ And I’m screaming. ‘This has to change.”

“They said, ‘Ok, why don’t you guys go out and have lunch or something and come back. We’ll change it meanwhile.’ So, we go out and have lunch. Ok, let’s go back and look at the marquee. They changed it. It said Al Kooper and Steve Katz’s Blood, Sweat and Tears. I said, ‘Bobby, I can live with that.’”

Blood, Sweat and Tears was all about charts whereas The Blues Project was all heart and soul. For all intents and purposes, The Blues Project died when Steve and Al joined BS&T.

“I mean, Blood, Sweat & Tears was a head thing. It was well written but again, it was a head thing. It wasn’t a heart thing. I was reading charts whereas the beautiful thing about the Blues Project was that every performance was different. It was never caught on an album which is really the shame.”

Evolution is the logical follow-up to Live at Café Au Go Go. It just took ’em 57 years to get there. Live at Café Au Go Go in 1965 proved that a white band could not only sing and play the blues, but use it as inspiration to produce a sound that should have been the springboard for an entire genre unto its own. Sure, Clapton, The Stones, The Yardbirds and countless other British Invasion and West Coast Haight Ashbury bands jumped off from the same influences, but The Blues Project took the blues farther away from its primary influences, and they did it with a bit of Big Apple bravado. Originally, Danny Kalb’s guitar work was the sweet spot, and Al Kooper pushed the envelope with his eclectic influences from pop to jazz.

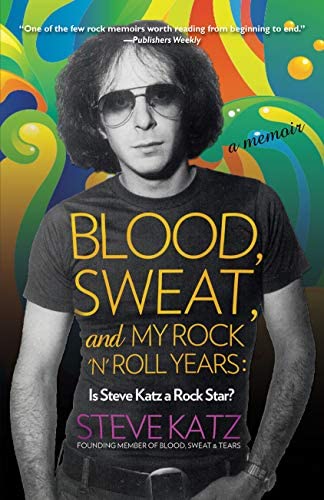

But even talking to guitarist Steve Katz today and reading his hilariously snarky memoir Blood, Sweat and My Rock ’n’ Roll Years: IS Steve Katz a Rock Star? I get the distinct impression that his take on the original band was that it was his sandbox, an adolescent lark and an entrée to sexual excesses.

These guys were a ’60s version of the Dead End Kids, and that’s just where The original Blues Brothers ended up, in a dead end. Looking back on the magic of their brief brush with fame, the two original members have crafted an album that disavows that old saw that you can’t go back home. Listening to the two albums back-to-back is like experiencing time standing still.

It’s as if all the things that happened musically between 1965 and 2022 have disappeared. The New York attitude is replaced with a comfort blanket of sage wisdom. Like the original, the songs here have a touch of jazz. But that influence comes from the heart, not the head, and does what blues and rock should do.

Put simply, this album is the shit.

Now into his second half century as the warrior music journalist, Don Wilcock began his career writing “Sounds from The World” in Vietnam, a weekly reader’s digest of pop music news for grunts in the field for the then largest official Army newspaper in the world, The Army Reporter. He’s edited BluesWax, FolkWax, The King Biscuit Times, Elmore Magazine, and also BluesPrint as founder of the Northeast Blues Society.

Internationally, he’s written for The Blues Foundation’s Blues Music Awards program, Blues Matters and Blues World. He wrote the definitive Buddy Guy biography Damn Right I’ve Got The Blues, and is currently writing copy for a coffee table book of water color paintings of blues artist by Clint Herring.