“People are always disappearing. All over rural America, they come and go,” Mark Bingham tells me, this time from his car as we try our phone call again. Like the phone reception in Arnaudville, a Louisiana town in St. Landry and St. Martin parishes, the same could be said for generational trends this veteran producer and guitarist/singer-songwriter/arranger has surely seen come and go like flashes in the pan.

In the ‘60s, when a high school-aged Bingham was signed to a publishing contract with Elektra Records, there were about 300-400 records a year coming out. “Now it’s like 300-400 records a day coming out. Who can find anything?”

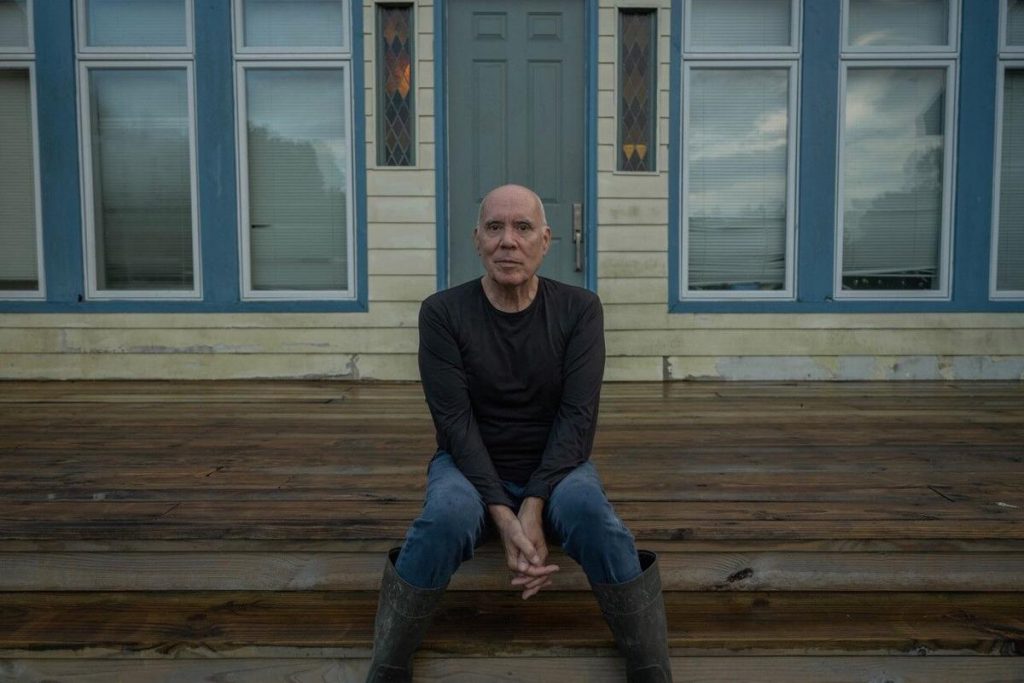

Just 300 yards away from his residence out in the country is Louis Michot, perhaps best known as lead singer/fiddler for Lost Bayou Ramblers. For the past five years, Bingham has been a member of his cosmic country Cajun group Michot’s Melody Makers. And now a total of 22 Bingham works will be rolled out over the next year via Michot’s own Nouveau Electric Records label. Chronicling over 50 years in no particular order, the retrospective series lifts a curtain on his invisible world that operated behind the scenes the whole time he was producing other people’s music. Some are reissues of long out of print albums, some newly recorded, and some are collections of miscellaneous songs.

One of the reissues is an eponymous 1981 recording from the Social Climbers, formed in 1979. The trio consisted of Bingham on guitar and vocals; Jean Seaton Shaw on bass; and A. Leroy on Farfisa organ and Korg Rhythm Machine. The record, he tells me, has actually been released a few different times. The first label was Bloomington, Indiana’s Gulcher Records, one of the earliest independent labels known for their release of one of the first punk records: the Gizmos’ first EP. “The guy moved to Hoboken Records, and then it came out on Hoboken Records. And then it came out on a Japanese label for a minute.”

Then the record came out on Drag City, who had it from 2011 until recently. Bingham wanted to keep it in print. “Or keep it in stream or whatever you call it,” he says wryly. The new version will have 10 extra tracks, both live and in the studio. “There was a point where this guy Wharton Tiers was in the band playing drums. So there’s a lot of the tracks with Wharton on there and some live stuff. And then at the same time, there’s another record that was all live Social Climbers, but it was something that mutated so much. I didn’t even call it Social Climbers, and I wish I had never called in Social Climbers; it was a bad joke.

“I had this band with Jean Shaw, and it was two of us. I was playing with Glenn Branca, and Glenn and his partner Barbara Ess started this magazine called Just Another Asshole. They said, ‘You want to play the Mud Club for the Just Another Asshole benefit?’ I was like, ‘Sure.’ So they said, ‘Well, what should we call the band?’ I didn’t have a name. I said, ‘Oh, just call it Social Climbers.’ Everyone in SoHo was a social climber. So it was a bad joke. It’s supposed to be like a one-shot gig and then it stuck, which is really embarrassing.”

At that time in New York City, the rent and overhead to live was so miniscule compared to now that he and his band could rehearse as many times as four times a week. “The keyboard player in the band had a basement studio underneath Fanelli’s on the corner of Mercer and Prince in the area of SoHo, which now would probably be $4,000 a month if not more. That was Action Central; a lot of people rehearsed there. There was the downtown scene, and then there was the other scene, which was more like New York Rocker and CBGB’s.”

Bingham worked for the label Red Star Records and produced a record for them that never came out. “Marty Thau, who was a brilliant, funny cat and was the New York Dolls’ and Melanie’s manager, started this label.” Marty was also manager of the underground band Suicide. “There’s a live Suicide record that I made that’s still floating out there that may come out. It was about to come out, and Alex Ebert was going to put it out on his label. And then Alan (Vega) had the bad taste to die on us. Since then we sort of sat there like, ‘Oh, well, what do we do with this?’ Then there’s a live Red Star record with Von Elmo, Walter Steding, the Fleshtones, and Suicide that was never released.

“There was a lot of music going on, and if you were a New York band, you could travel,” he says as he casts his mind back to a time of cold calling clubs and snail-mailing packages with cassette tapes and pictures. “I remember Thurston Moore saying (Sonic Youth) used the Social Climbers’ package of where we had played, to book their first tour. They went to all those people. We were following Bad Brains one day apart for about six weeks once in ‘82. It was a different world; get in the van, sleep on people’s floors. New York was rough. We were not part of that scene.”

Bingham left New York in 1982 and acclimated to the New Orleans music scene. On his return trips, he would work with Saturday Night Live musical director and longtime collaborator Hal Willner on a number of tribute projects including A Tribute to Thelonious Monk. From coming home to Hal’s apartment, jumping into bed and landing in cat feces, to waking up to Courtney Love poking him, Bingham has so many Hal stories that he wouldn’t even know where to start. One story that still blows his mind, and which makes him “conscious in this old age,” is when he realized the guy he had been having conversations with for a week on Hal’s couch was a down-and-out but astute Terry Southern (best known as the screenwriter behind Dr. Strangelove and Easy Rider).

“It was ‘84, ‘85. And there was this old guy sleeping on the couch named Terry. He was really smart and really funny. I mean, I would go to New York to work on these things that had no budget. I couldn’t stay in the Chelsea Hotel. And this guy was one of the greatest writers of the ‘50s and ‘60s. I mean, screenplays, books, the whole deal. Brilliant cat. You can do your whole life and end up sleeping on Hal’s couch when you’re 75.”

Bingham’s debut as a leader came in 1988 on the Willner-produced I Passed for Human, and found guests such as Beat poet Allen Ginsberg on Bingham’s own originals. That same year saw the release of Stay Awake: Various Interpretations of Music from Vintage Disney Films. Natalie Merchant was hand-picked by Bingham to join in on his “Little April Shower” re-imagining, also featuring The Roches and Michael Stipe.

“Natalie was saying, ‘Well, we need somebody else to sing with you. What about Ian from Echo and the Bunnymen?’ I said, ‘Oh, yeah, that would be cool.’ He couldn’t do it, and then it was somebody else, then somebody else… And this is how out of it I was in terms of what was up in pop music – she says, ‘What about Michael Stipe?’ I was like, ‘Who is that?’ She says, ‘R.E.M.’ I was like, ‘Oh, I think I’ve heard of that band.’ Literally, I had no idea.”

Jefferson Holt, R.E.M.’s manager at the time, loved the sessions so much that he asked Bingham if he had any other stuff in the pipeline. “And I said, ‘Oh, I’m making a new record.’ Then Jefferson ended up putting that record out. I became sort of part of the whole R.E.M. posse, which was weird because Michael and Jefferson brought me in, and then Peter (Buck), Mike (Mills), and Bill (Rieflin) brought Peter Holsapple in.”

Bingham’s string arrangement is the first thing you hear on R.E.M.’s “Shiny Happy People” from the 1991 album Out of Time – his waltz-like melody teeing up the sardonic nature of the song. It was the first R.E.M. song to reach the top 10 in both the U.S. and the U.K. “I remember Peter sent me a note saying, ‘I want a French horn on this. I want this on this.’ So I sort of got instructions. Everything that I did on that record musically was already inherent in the particular song. Popular music arranging, it’s a whole different animal for songs than it would be for – it’s not Nelson Riddle, you know? It’s not the old school stuff at all. And now that’s 30 years ago, so everything has shifted. That’s when hip hop was dangerous and we put KRS-One on the record.”

In 2001, Bingham opened Piety Street Recording, and in 2013 the most in-demand studio in New Orleans shuttered its doors. He set up shop in Henderson before relocating to his current studio in Arnaudville. In its 12 years, Piety Street’s projects included albums by John Fogerty, Dr. John, Elvis Costello & Allen Toussaint, Hal Willner’s Rogue’s Gallery, Green Day, Marianne Faithfull, Steve Earle, Dave Matthews Band, Peter Stampfel, and Lost Bayou Ramblers. Does he find good people to work with, or do they find him? “I’m fricking 73 and I’ve been doing this since 1966. What the hell?” he blurts in a tone of slightly bemused thought.

“If you had told me seven years ago that I’d end up living out here and playing with Louis… Things just transpired. I’ve been working with Lilli Lewis all the time, and she is just a force.” I’m a great admirer of Bingham’s varied works, whether he’s playing guitar on them, producing them, or both. And Lilli Lewis’s 2021 album Americana sticks out like a single, gleaming violet on the genre’s hallowed, homogenous turf. Instrumental in turning the tide in a direction that is diverse in every sense of the word, “Lilli is one of the only people on the planet who can sing and accompany herself on the top 10 arias for soprano in the opera world.”

“It’s funny, I just mixed something and sent it to her. And we have this running gag about bass solos. On her last record, I cut a bass solo out because I thought the song was too long. So Lilli gives me this big lecture about black people in bass solos, but it was comedy the way she presented it.”

The song? “One Shoe,” a song I initially took special notice of because of its memorable bassline, which Bingham ended up reinstating.

“So I just mixed this – she’s got a new version of a song that I gave her that was a rewrite of ‘Wondrous Love,’ an old 19th century hymn. I’d done a different thing with it, and then she took that and did a whole ‘nother thing with different words. And then she melds that into ‘Woodstock’ by Joni Mitchell. So in the middle of all that is this bass solo. She sends me a funny text saying, ‘I feel like my piano is fighting with the bass on the bass solo.’

“But Lilli was so badass. I was like, ‘Let’s do this. You just play and sing. We gotta start there. So we made a record. It’s taken things like promotion from Mandy Patinkin (Inigo Montoya fame) to get people to take her seriously…” Bingham performed with Lilli at this past Americana Fest for its inaugural NOLAxNashville showcase, where Lucinda Williams made a surprise appearance. He also joined Lilli on a panel about LGBTQX artists in Americana.

Bingham listens to and absorbs music from all over the world and has spit it back out on his own terms in every capacity he’s been in. Not everyone does that, and certainly not everyone gets that. How was something like the Social Climbers’ angular and experimental debut album received then, and how will it be received now? “People are used to songs that are about yourself. Like, you know, I did this, I did that. I want you, I want this part of your body. I want to possess you. There’s nothing like that on Social Climbers’ stuff. It’s very out there in a sense that it tells stories that don’t have anything to do with real life. The singer is a character, not expressing or bearing his soul. That’s kind of weird for people. A little too literary; a little too out there. So, I expect that. Early on we got shit about the drum machine because there was hardly anyone doing that at that point. And we were touring with drum machines; that used to wig people out.”

The electronic machine thing has come full circle in a poetic way. Michot’s Melody Makers recently played a show with one man-band Quintron. “We did a show with Quintron that was great. He did the Drum Buddy on all these archaic 1920s Cajun tunes. And it really made it sound like an old blues thing in a way, you know?” Quintron has patented several inventions, and his most celebrated is the Drum Buddy, described as “a light activated analog synthesizer which creates murky, low-fidelity, rhythmic patterns.” Clients include performers Nels Cline of Wilco, Laurie Anderson, Fred Armisen, and DJ Mr. Dibbs.

Michot’s Melody Makers’ second album, 2020’s Cosmic Cajuns from Saturn, was recorded live at The Saturn Bar in New Orleans. Boiled down to its essence, the album is as forward-thinking and kaleidoscopic as it is deep-rooted in Cajun string band traditions. “I don’t like knowing how the sausage is made,” he jests.” I’d just rather hear it and see what it sounded like. But as it turned out, for a variety of reasons, I ended up mixing it and putting it together, which wasn’t the plan. But that’s what happened.”

He thinks of the vast release series as a “deep breath of summary,” in which 11 of the albums will be instrumental LPs. “I think it’s going to be really interesting to people, because that’s kind of what I’ve been doing on the side all this time. The popular music with songs that have singing is a whole different thing. I’m still making songs; I’m still working like that. Mostly I’ve made a lot of crazy stuff that was for all kinds of reasons, but not the kind of thing that ends up getting put out. I’ve never been Nonesuch material; I didn’t play in that world. I didn’t play in the get-a-grant and become-a-famous-composer world.

“I’ve been doing this whole other thing that’s really outside a lot of the genres that are out there. The stuff from Indiana is interesting. A record that’s not even on this batch, IN THE EYE by the Screaming Gypsy Bandits from 1973, that’s on this other label called Numero – they’re going to press that on vinyl next summer. I will do a good, long two-hour show at The Granfaloon Festival that covers about 50 years worth of stuff.”

So far, solo recordings Goo Seneck and Mushroom Crowd have been released. Premiering exclusively today on ABS are two more titles, To And From The Afterlife (recordings from 1989-2020) and William Blake In Bakersfield, both out January 20.

Bingham describes To And From The Afterlife as “storytelling, reconstructed Lomax, decomposed Cajun history, EtherRock meets EDM, small orchestra and spoken word, surreal murder ballads about raptors, Death, death, life, and more death.” Contributors include James Alsanders, Carol Berzas Jr., Joe Cabral, Allen Ginsberg, Raymond “Moose’ Jackson, Anthony Cuccia, Sarah Quintana, Michael Cerveris, Helen Gillet; Ralph Carney, Jim Kolacek, Amy Trail, and Michael Cerveris. This album was recorded at Piety Street in New Orleans, LA, Nina Highway in Henderson LA, A+R in NYC, Bearsville in Bearsville, NY, PDF in Arnaudville, LA, and Three Ring Circus in New Orleans.

William Blake In Bakersfield could be characterized as what he calls “art-damaged rock.” Contributors to this project were: Kirkland Middleton – drums; Bryan Webre – bass; MB – guitar, vox, virtual synth; Sam Kuslan – keys; Michael Cerveris & Lilli Lewis – harmony vocals; Tom Marron – harmonica; Louis Michot – fiddle; Richard Comeaux – pedal steel; Tom Lingard – drums; Jimbo Walsh – bass; Glenn Patscha – keyboards; Joe Cabral – tenor sax; Cassie Francillon Watson – harp; Janna Saslaw – flute. The album was recorded at Nina Highway in Henderson, LA, PDF in Arnaudville, LA January 2021- April 2022.