Otis Taylor born in Chicago in 1948, is an American blues musician who plays guitar, banjo, and harmonica. At a young age he moved to Denver, Colorado, where he grew up. His first musical instrument was the banjo, and he drew inspiration from the Denver Folklore Center where he first heard Chicago blues, Piedmont, Delta, and country blues. While in London in the 1960s, Taylor earned a record contract with Blue Horizon Records, but soon after parted ways returning to Boulder, Colorado where he played with Tommy Bolin, Zephyr, and the 4 -Nikators. In 1977, he changed careers becoming an expert in high-end antiques and a bicycle racing coach.

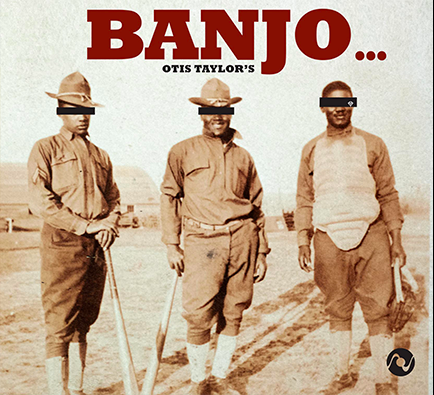

In 1995, he returned to music performing at the opening of Buchanan’s Coffeehouse on University Hill in Boulder, Colorado. In 1996, he released his first solo album, Blue-Eyed Monster. In 2000, Taylor released his breakthrough album White African, produced by Kenny Passarelli. His music has been featured in the films The Badge, Shooter, Public Enemies, and The Least Among You. He even made an appearance in the 1986 film Crossroads as a jook house musician. Taylor’s 15th album, BANJO, recorded at Octave Records in DSD studios in DSD256 is now available. The album was recorded in Boulder, Colorado over a two-week period.

Can you talk about your record BANJO and the recording process?

We did it in a thing called Pyramix instead of Sonoma or Pro Tools, which gives you DSD (Direct Stream Digital). Basically, this is what I did. I did five old songs and six original songs. I do this sometimes; I revisit old songs.

The banjo is a huge part of your life. Can you talk about this?

Well, yes and no. If you Google me, they won’t say that I play banjo. Try it on Google, it’s unbelievable. I have a banjo song that has almost 3 million hits on YouTube, so go figure. I just don’t play it all the time when I play a concert. I am not obsessed that I have to play the banjo for half a set or something.

My biggest influence was a guy named Dock Boggs who was an old timey banjo player. I really liked Dock Boggs a lot as he was very trance-like. I was playing a bit of Delta guitar too. I play the guitar the same way I play my banjo. I can play traditional fingerpicking banjo and a little bit of bluegrass, but I’m not very good at it.

What is “Trance Blues?”

Things that are hypnotic, like voodoo music and Ravi Shankar. It’s music that doesn’t concentrate on a chord change. If you hypnotize somebody, you tell someone to look at something and it spins around. That is what it is. You can use different types of music. I use blues. It’s just repetition. Sometimes Irish, Gypsy, and West African music is trance-like.

Being born in Chicago, who are the Chicago blues musicians who inspired you the most?

I left Chicago when I was four years old. My accent is from there, as you get your accent by the time you are four years old. You get into different artists at different times. When I was young, I was into Junior Wells and Muddy Waters. I saw Hooker, and I sat in with Muddy Waters when I was 16 playing the harmonica. I’ve seen Junior Wells, and I’ve been onstage with Buddy Guy.

I’ve seen a lot of people. Even when I saw Charles Lloyd – he’s a jazz guy – that was really cool. I saw all the Rock guys. I’m 74, so I was there when all that stuff was going on. Things that influence me are things like Gypsy music. Things out of your culture are an influence; things in your culture are not an influence.

How did your song “Ten Million Slaves” get in Public Enemies, the Michael Mann film?

I was playing the Chicago Blues Festival and Maria Norman came to the stage and said, “Michael Mann would like to have a meeting with you. He’s interested in your music for this movie he is making.” At the time, I didn’t know who Michael Mann was. Later, I realized he did Miami Vice and I realized who he was. I had to Google him and I was like, he’s that guy. I love Miami Vice. I met him at a pub in Chicago and he told me he really liked “Ten Million Slaves” and another song. He used two songs in that movie.

How does Colorado influence and inspire your music?

God, I don’t know. It’s just where I live. I don’t think it influences shit. I was raised in a black neighborhood and I live in Boulder. I guess it’s the upper-class Boulder suburbs. It’s just a life thing. I live in Colorado as it’s safer and nicer. It has nothing to do with my music.

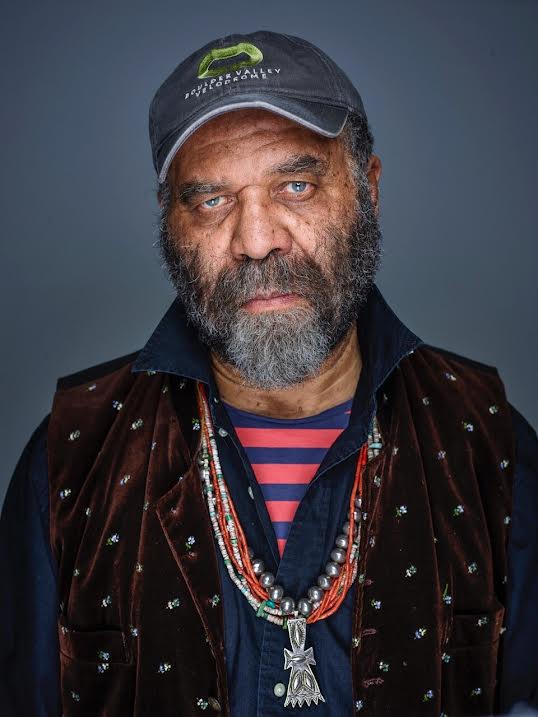

Can you talk about the different necklaces you wear?

I have been wearing Native American jewelry since I was sixteen years old. I used to wear moccasins in high school. I was always into that stuff.

Can you talk about your Blues in the Schools program “Writing the Blues?”

It is something that my wife Carol thought of. It’s about going into the classroom when kids are little and get them to learn how to write a blues song — writing the blues and singing the blues. Everybody has the blues. I’ve done it in Canada, Washington, Colorado, and at a lot of public schools. I used to do three or four a year at younger public schools.

You retired from music for a while starting in 1977. What did you end up doing, and why did you come back?

I got involved with bicycle racing. I sponsored Black bicycle racers and some Scandinavians. I knew that Blacks used to race bikes and Major Marshall Taylor was the world champion in 1901. I was part of the movement in the 1980s.

What is your songwriting process like?

It comes to me in one day. It’s either in practice or when I’m driving down a highway, a song comes to me. It is not a conscious thing, but I am not spiritual. It happens when my mind gets relaxed and goes into another space. When you wake up you are in another space or when you drive and you don’t remember getting there. This space is where I write songs.

What keeps you motivated to keep playing?

During the pandemic, I didn’t pick up an instrument for six months. When I had to start playing again, I really had to practice. I don’t live for music and I look for other things. I’m not the kind of person who has to play the guitar for five hours a day. I’m not obsessed with that. Maybe this is what keeps it fresh. I hire people that play guitar five hours a day.

What’s next for you?

The photograph on the cover of my new record BANJO with the eye thing, that’s my artwork. I started a movie during the pandemic about being the bicycle coach for Black riders. I don’t know. I’m getting old. I’m concentrating on some other things. We will see what happens.