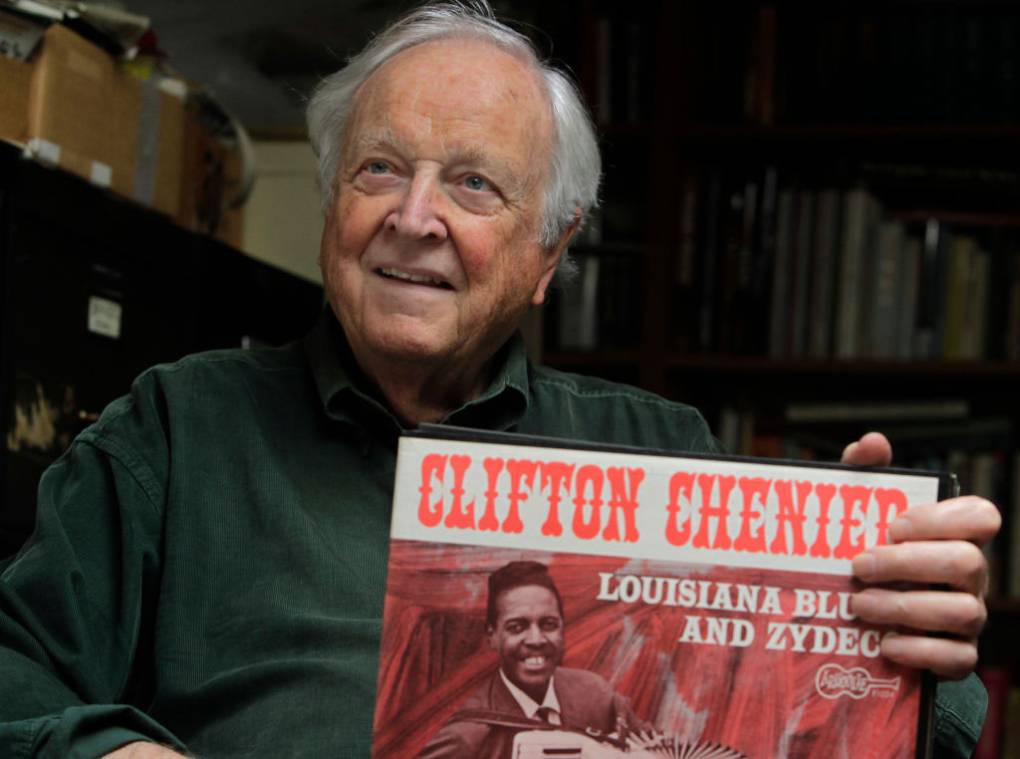

Chris Strachwitz, founder of Arhoolie Records died on Friday, May 5th. He was 91. “I was just a fan,” he told me in 2011. “I just became addicted to various American vernacular music and just found it a most amazing experience like some people like to go on safaris or go to the North Pole and climb the highest mountain. I just love this whole adventure of going to Texas and meeting this whole part of America I had never any idea existed: New Orleans and Memphis and Mississippi and Appalachia. That was to me the great adventure of coming to this country. These unbelievable ethnic groups of all colors and creeds, they all have their spit-kicking music. They kicked ass. They weren’t this wimpy shit from Europe.”

While in Mississippi doing field recordings, Chris Strachwitz once bought a cache of jukebox records that included a Robert Johnson single which he then sold to John Fahey for $5. “I didn’t think anything special of that damn record,” he told me, but he released a lot of records by talented artists that other labels ignored.

Strachwitz may not have recognized the potential value of that Robert Johnson record, but he knew what he liked, and his recordings inspired and influenced multiple generations of artists and blues and folk fans.

Arhoolie Records was a fiercely independent label that celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2011 with three concerts at the Freight and Salvage in Berkeley, California. All proceeds benefitted the Arhoolie Foundation. Hosted by NPR “American Roots” host Nick Spitzer, the concerts included appearances by Taj Mahal, Treme Brass Band, The Campbell Brothers and Ry Cooder.

In an interview published that year, Strachwitz described the impact Ry Cooder had on him and – it turns out – the impact his work had on Cooder. “(Cooder’s playing at another Arhoolie benefit) was the toughest thing I’ve ever heard from any white kid, and afterwards.”

Cooder returned the compliment. “You know, when I was a teenager I drove into downtown L.A. I took a bus, and I found this album by Big Joe Williams. It was on the Arhoolie label. I took it home, and it just blew me away. It was of course Big Joe’s most fierce record he’s ever made. He was just out on bail, and he was just scared shitless, and I don’t know. I’m just glad I caught it, but the poor guy.”

“I just wish I’d been able to do more for Big Joe, but how that record impressed this young white kid, you see, I never thought about that,” explained Strachwitz. “People wanted to play this music. I thought I was capturing these audio snapshots, and I felt, ‘Well, I hope people enjoy listening to this although they can’t experience the whole environment that I encountered and meeting these people and all that, but it just absolutely hit me when Ry did that. And I guess there were others that were blown away with some of this music.’”

Nick Spitzer of “American Routes” in 2011 said of Strachwitz, “In an era where Mo Asch is long gone, Harry Smith is remembered for re-issuing 78s, and Alan Lomax is revived by John Szwed’s great book (The Man Who Recorded the World), the last man standing, the (literally) tall tree, is Chris Strachwitz of Arhoolie Records. He is a field recordist, studio producer, and re-issuer of 78s without parallel.”

Grateful Dead historian Dennis McNally in his Highway 61 book on the origins of Americana roots music talks about the white blues fans who went and found the lost musicians like Mississippi John Hurt and Skip James, “but one of the special things about Chris,” says Dennis, “was that he simply saw the ‘found’ musicians as human beings.”

Dennis quotes my favorite music journalist Peter Guralnick on Strachwitz: “We also consciously or unconsciously tried to shape the music that they played on stage. [By asking for specific songs or instruments.] The same statement could be made for the guys running Paramount during the thirties, but at least their motive was simple profit, which motive the artist shared. Our motivation was a strange combination of ego, scholasticism, and power.”

Dennis continues: “It became uglier still when the researchers fell out and fought with each other. Some of them were clearly exploiting their situation, and overall only Dick Waterman and Chris Strachwitz of Arhoolie Records saw the rediscovered bluesmen as real breathing humans.”

I would give Rounder Records equal credit for doing just that. Label co-founder Bill Nowlin says, “The two labels that most inspired Rounder to emulate were Folkways and Arhoolie. That both covered an array of musics – in Arhoolie’s case, blues and Cajun and a bit of bluegrass – was something that Rounder did as well.”

Arhoolie Records released albums by Mance Lipscomb, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Big Joe Willaims and Clifton Chenier. They also recorded Cajun, Tejano, Zydeco, gospel, country, jazz, Mexican regional and traditional down home music from around the world.