The blues giant Chester Arthur Burnett, better known as Howlin’ Wolf, was one of the most influential blues musicians of all time. A true paragon of the blues, he brought the music of the Mississippi Delta to Chicago in 1952. In remembering his art and legacy, here are 10 things you may not know about Howlin’ Wolf.

1. Howlin’ Wolf was born June 10th, 1910 in White Station, Mississippi, just north of West Point, Chester Burnett grew up on the Young and Morrow Cotton Plantation near Ruleville. His grandfather would tell him and his siblings stories of the wolves in the area.

Once, something frightened the young Chester and he ran howling upstairs, which prompted his family to dub him the Howlin’ Wolf. At just one year old, his parents separated. His mother left him with a stern, unforgiving uncle. He ran away at age 13, finally finding an inviting home with his father’s family. It was his father, Dock, who gave Wolf his first guitar at the age of 18.

2. Howlin’ Wolf spent two and a half years in the US Army. For part of that time, he was assigned to the 9th Cavalry Regiment, famed for being one of the units dubbed “Buffalo Soldiers.” He participated in the largest military exercise ever held in the United States, The Louisiana Maneuvers, in 1941.

It was there that one of the earliest photos of Wolf was taken, showing him cleaning the frog of a horse’s hoof as a senior NCO looks on. Still a horse cavalry unit while Wolf was a member, the 9th was deactivated in March, 1944. That made Burnett one of the last true cavalry soldiers, as well as one of the last Buffalo Soldiers in the army.

3. Wolf spent most of his early life as a farmer, both in Mississippi and Arkansas. However, growing up in the Delta at that time gave him unique access to the blues masters of the area. He learned guitar techniques and showmanship from Charley Patton, the ins-and-outs of the harmonica from Sonny Boy Williamson II (who was married to Wolf’s step-sister, Maggie), and tried to emulate the yodeling of his idol, Jimmie Rodgers.

He also played with Robert Johnson, Johnny Shines, Honeyboy Edwards, Son House, and Willie Brown. Burnett was also married to Brown’s sister for a short time. He took other jobs to help pay the bills as well. One of these was selling advertising on KWEM Radio in West Memphis, Arkansas. He would also play his music during a 30 minute planter’s show on that station, which eventually earned him a recording contract.

4. Ike Turner produced Howlin’ Wolf’s first records. Turner was then an A&R man for RPM Records, and served as his piano player. He used the recordings to secure a contract with Sam Phillips at Sun Records in Memphis. Those two original songs, “How Many More Years,” and, “Moanin’ at Midnight,” became the Wolf’s first two hits after being sold to, and released by Chess Records in Chicago.

“How Many More Years,” holds a couple other distinctions. Recorded at Memphis Recording Service around July of 1951, and released as a B side by Chess on September 15th of that year, it shot to the #4 spot on the charts. Writer Robert Palmer has cited Willie Johnson’s guitar work on the track as the first use of the power chord.

Producer, T-Bone Burnett (no relation), said, “In some ways ‘How Many More Years,’ by Wolf would be the first rock ’n’ roll song because that has the guitar lick that became the central guitar lick in rock ‘n’ roll, and that’s the first time we heard that played on a distorted guitar.”

5. In 1952, Wolf drove his own car to Chicago to join the Chess Records stable. It was there that one of the greatest love-hate relationships of the blues began. When Wolf got to the Windy City, he contacted fellow Mississippian, and Chess label-mate, Muddy Waters.

“I got in touch with him because I didn’t know nobody here,” Wolf said to reporter Peter Guralnick. “He carried me around to the clubs and helped me get started.”

The friendly rivalry, which has been much overblown in literature and on film, was rooted in a grudging admiration of one other. Waters is recognized for having the all-around better band, while Wolf is known for his powerful stage presence as well as his business savvy.

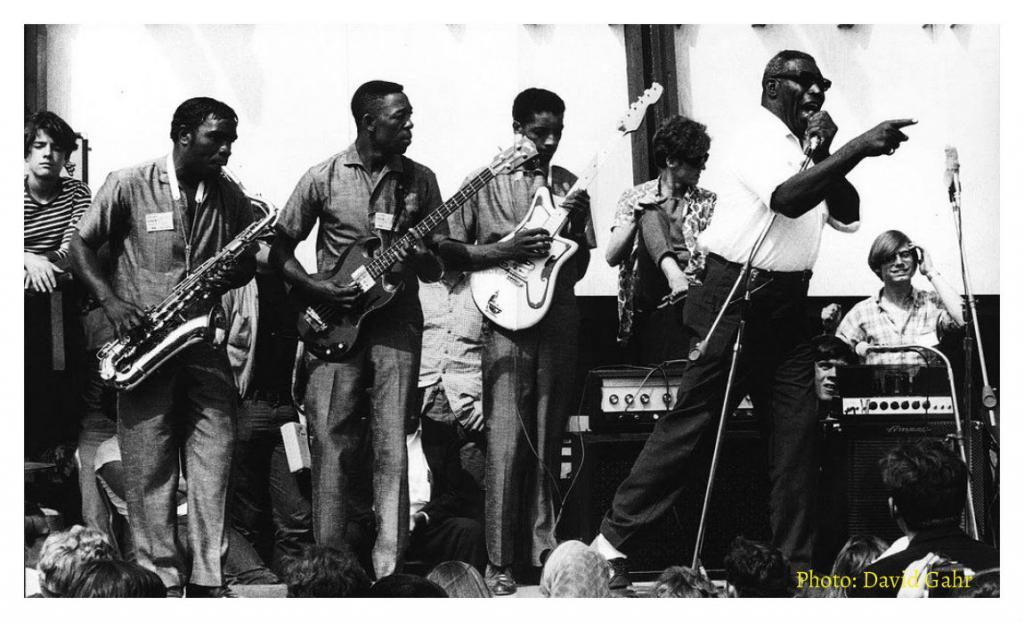

Around 1956, Muddy stole Hubert Sumlin from Wolf’s band for a short time, while in 1969, Wolf stretched out his set at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival, attempting to keep Waters from performing. After the release of Waters’ Electric Mud, Wolf released his own “psychedelic” blues album, The Howlin’ Wolf Album, which he later regretted and dismissed as “dog shit.”

While Waters was more of a “company man,” for Chess, Wolf would speak his mind, in no uncertain terms. However, they both emerged as the combined force that created the post-war Chicago blues, much to the credit of Willie Dixon, who wrote dozens of hit songs for both artists.

6. Howlin’ Wolf was functionally illiterate into his 40s, but eventually received his GED and later studied business and accounting. He couldn’t read music. He depended on long rehearsal sessions, demonstrating what he wanted until his backup musicians understood. In 1972, he received an honorary doctor of arts degree from Columbia College in Chicago.

7. Wolf paid his people a fair salary, on time, and withheld unemployment insurance and even Social Security. He also offered them health insurance benefits. He was not an extravagant man in his personal life. Burnett and his wife Lillie, along with her two daughters, lived in a modest, yet comfortable home on Chicago’s south side. He never wore a great deal of jewelry, or drove flashy cars, preferring a Pontiac station wagon to the Cadillacs driven by his peers. He hunted and fished, owned farmland in Arkansas, and volunteered with the local fire department.

8. Suffering from kidney disease, and having suffered several heart attacks, Wolf kept on recording and performing. The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions album, recorded at London’s Olympic Studios, for example, saw him taking dialysis treatments in the studio between takes.

His final, live performance was in November, 1975 at the Chicago Amphitheater. Sharing the bill with B.B. King, Albert King, O. V. Wright, and Luther Allison, Wolf performed as he always did, even crawling across the stage during the song, “Crawling King Snake.” The crowd gave him a five-minute standing ovation. When he got offstage, a team of paramedics were called in to revive him.

9. The Howlin’ Wolf Foundation was established by his step-daughter Bettye Kelly to preserve and extend Wolf’s legacy. The foundation’s mission and goals included the preservation of the blues music genre, scholarships to enable students to participate in music programs, and support for blues musicians and blues programs. Currently, no information on the foundation, its work or tax status is available.

10. Contrary to popular opinion, Howlin’ Wolf was happy the young British and American rock bands were covering his songs. A 1967 interview with Chris Strachwitz, for his radio show Music in America told the story. “Well I’ll tell you, there’s nothing wrong with that. I want all of them to make my records, because I gets money out of it, see,” Wolf explained. “It doesn’t matter no different who sang your song. They sang because of the way they feel. Don’t never take and try to change a musician when he does something. Let him play the chords the way he feel.” (All interview rights reserved by the Arhoolie Foundation)