“I couldn’t speak. I wouldn’t make any noises. I wasn’t even crying. My aunt thought I was mute.”

D.K. Harrell was two years old.

“So, one day, my grandfather gave my mother Deuces Wild and said, ‘Play this in the car when he’s crying.’ The song ‘The Thrill Is Gone’ came on, and I started singing. She almost wrecked the car. For a while she thought, ‘My baby’s not gonna speak. He’s not gonna talk.’ And I had a lot to sing about that day, and have been ever since.”

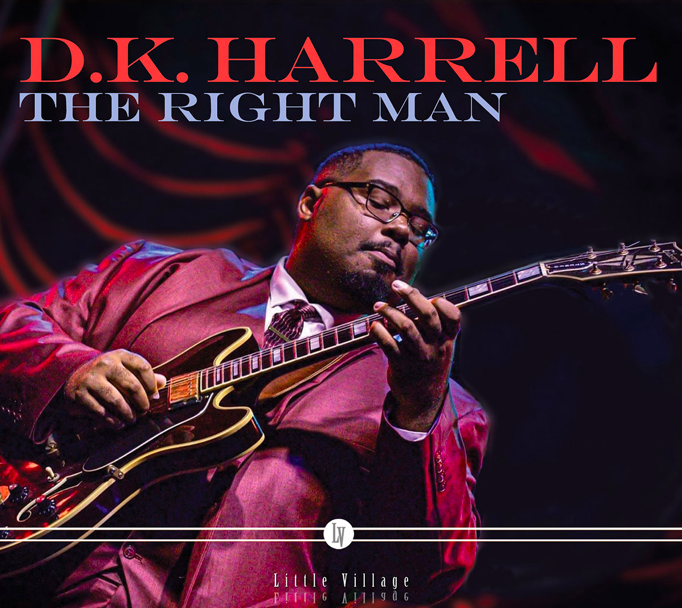

D. K. Harrell performs Friday, October 6th at noon on the main stage of the King Biscuit Blues Festival. His debut album, The Right Man, is topping the charts, and he’s being touted as a blues star – almost an oxymoron, particularly for a musician who is only 24 years old.

“It’s not the cover of the book that defines the book. It’s the first page,” says a young man wise beyond the years with a style of guitar playing strongly influenced by B.B. King. The 11 cuts on The Right Man are all original songs mostly about relationships that cut deeper than most blues classics.

He’s an anomaly in so many ways. “I was born in Ruston, Louisiana in the black community. The dominant music for young people is hip hop and rap. Back in the 2000s I’d have a CD player in my pocket. ‘Hey, what are ya listening to?’ I’d open up my CD player to James Brown, and they’re like ‘James Brown? That music is old,’ and I’m like ‘I know it’s old.’”

He remembers the last conversation he had with his grandfather before he passed. A man who played the music of blues legacies all the time, he told his young grandson, “D., be a leader. Take care of business and always remember that time waits for no one. Do what you can now. When life says you’re ready to go, you don’t need to regret in your soul. So, do everything you can.

“He was the father I never had and, when he left this world physically, he really was a piece of my heart. He really was on my mind, and my heart hasn’t been the same since. He is the reason why I focus so hard on a lot of stuff.”

It wasn’t easy growing up in rural Louisiana. Young D. dressed like a gentleman. He was overweight and he liked old music. “I got called ugly a lot. I wasn’t athletic. I wasn’t the most handsome man in school. So, yeah, I stuck out.”

His music made him stronger. “Music ended up kind of my friend. It was all I had. Of course, I had my mother. The blues kind of filled some holes my mother can’t fill. It’s just been my best friend ever since.”

The church both helped and hurt him. “When I was playing blues, I wanted to play harmonica in church, and they turned away from me. They kinda didn’t want me doing that. Then when I played it for Mother’s Day in 2019 right before the pandemic happened, we had a different pastor, a different music director. My mother begged me to play that day for Mother’s Day, and I was afraid. Man, they’re gonna kick me out of the church. They’re gonna complain. and I played on that Mother’s Day, and they came over. The new pastor was like, ‘Do you want to play in church every Sunday?’

“I think he was just surprised at how I take the blues licks and apply them to gospel, and not make them sound like blues. It was fun. It was weird. They were kind of unaware of how close (blues and gospel are). At the same time, they were aware of the changes like the cord changes of gospel and blues and licks. They’re natural. So, it puts it into the what-the-hell-is-going-on situation, whatever it is.”

D. K. is one of five Little Village acts appearing at King Biscuit. The only one of the five appearing on the main stage (see article on Little Village acts at festival).

Little Village offers to record their artists’ music at no expense to the artist at all. Sometimes, this is the very first time the artist has been recorded. Not only is there no expense to the artist, but the label gives each artist 1000 copies of their CD to sell on tour. The artists retain their “intellectual property,” and Little Village sets up all retail accounts for the sales of CDs in the artists’ names. This happens with generous public donations and grants.

D. K. Harrell could almost not believe his good fortune to be signed to Little Village. To have seasoned veterans like guitarist Kid Andersen and pianist Jim Pugh recording with him was a gift he never expected. Bass player Jerry Jemmott was particularly a joy. “I honestly thought getting Jerry Jemmott was a joke. I thought Kid Andersen was pulling my leg. And he calls me about a week or so later. He says, ‘Well, Jerry Jemmott is going to be on your record,’ and I was very delighted. So, you have Tony Coleman, B.B.’s drummer, and Jerry Jemmott who is the bass player on ‘The Thrill Is Gone’ and many other hit records like Aretha Franklin. That was just extremely exciting and overwhelming.”

“Kid (Andersen) just has the touch, man. I think what it is, is that Kid has a genuine love of the music. He doesn’t see it as another check or another project. He actually put his heart and soul into engineer what the artist is trying to do.”’

D. K. Harrell promises to be one of those artists that years from now you’ll say you saw first at the Biscuit. In our interview I told him to beware of one pitfall. When Koko Taylor passed, her daughter wanted to make Shemekia Copeland the new Queen of The Blues, and Shemekia said, “There’s one queen.” I told him not to let anyone talk him into becoming the new King of The Blues. There’s only one king. That will not do his career any good.

“No,” he said. “I’ve been asked that honestly. One guy asked me. He said, ‘How would you feel if people tried to get you to become the new King of The Blues?’ I said, ‘Honestly, I don’t want the title. B.B.’s shoes are B.B.’s shoes. I’d be more than happy to be named the prince or heir to the throne or whatever (but) I can’t take that from B. B.”

D.K. needs his own title, his own space. Yes, he was inspired by B.B., but he also was inspired by a number of other artists, and he’s not a B. B. clone. He’s obviously an influence, but that’s just what that is: an influence.

“That’s true,” he responded. “I’ve had people try and give me their Lucille, their Gibson Lucille, and I’m ‘No, I don’t want it.’ ‘Why don’t you want it?’ ‘I got my own, and that’s who I am.’”

See part two of this interview coming tomorrow.

Mark your calendar for the date, Wednesday, October 4th for the start of a four-day wang dang doodle that proclaims the blues alive and well. You want legends and legacy? Saturday night headliner is Louisiana Wetlands firebrand Tab Benoit backed by The Big Easy’s Dirty Dozen Brass Band. This Grammy-nominated singer, songwriter and guitarist is home grown, but his dexterity on guitar is needle sharp, and his rapport with an audience is nothing less impressive than what I’d expect from an Apollo Theater crowd on a hot Saturday night in Harlem. It’s the kind of bonding that eliminates the distance between the stage and the fans.

Thursday headliner Ruthie Foster is the winner of seven Blues Music Awards and has been nominated three times for Best Blues Album Grammy. “I’m not just singing the blues, I’m singing my own story,” says this singer whose repertoire covers gospel, blues, jazz, folk, and soul. When she played the Biscuit in 2015, she told me it felt like home. Her music is “my story as a woman that’s grown up with gospel music. It’s really all these different types of genres being raised in Texas. I look at music as in the beginning it really was a way of healing for me in a lotta ways.”

Friday’s headliner offers the primal screams of Chicago South Side veteran Nick Moss and his very electric band. His music combines postwar electric sounds in the Chess tradition with hard rocking contemporary blues. If you like big city blues done with pinpoint precision and a hard edge, this is as good as it gets.