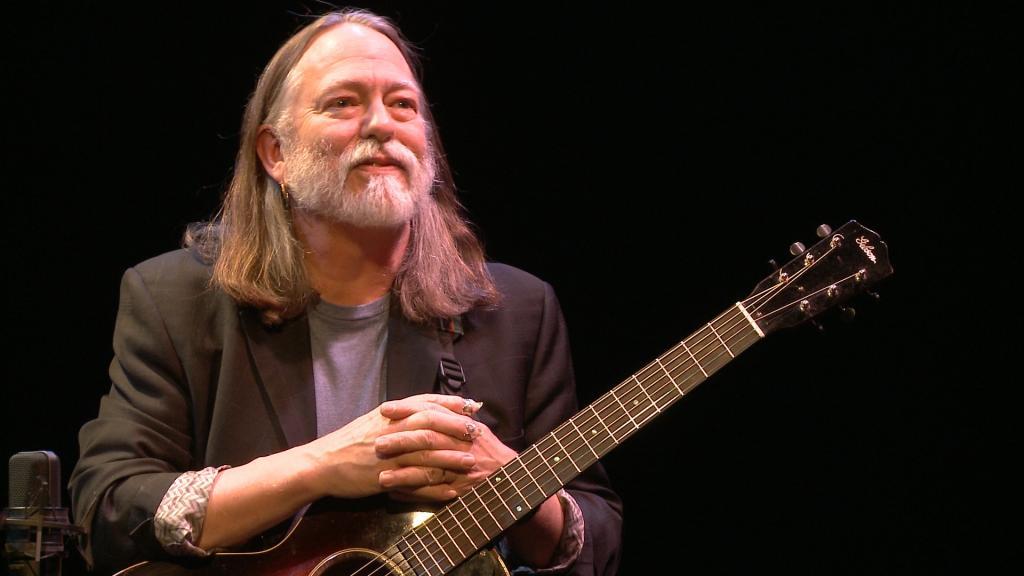

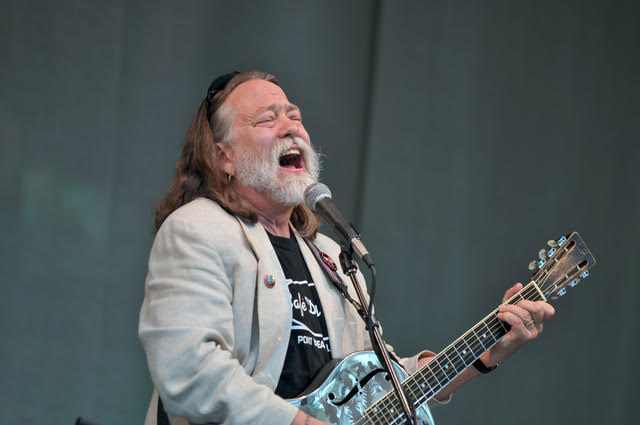

Scott Ainslie is a griot, a term usually applied to African sages who verbally chronicle their tribe’s history. In today’s world, there are a plethora of ways of documenting our culture including the one you’re reading now, but there are still portions of current society that get little recognized on social and mass media outlets like TV, websites, and cell phones. The irony of this is that we human beings spend vast portions of our time accessing these “communication” outlets often without really ever addressing the pulse of our lives.

Ainslie does that with his music.

Perhaps ironically, he performed at Old Songs in Voorheesville, New York on November 11th two doors down on a street past a huge sign that said, “Road closed. Local traffic only.” Next to that sign was another sign announcing in much smaller letters “Businesses open.”

Ainslie is a Phi Beta Kappa scholar who has spent his life chronicling the blues of the most lauded but little known Robert Johnson, as well as music of other artists through his one-on-one communication with mostly African American artists in the southeast. Ainslie also writes his own songs. One of those numbers he played Saturday is “Rice Grows” about Vietnam.

He wrote it after getting advice from his friend and fellow artist Tom Chapin. Ainslie repeated the back story in concert that he’d told me in an advance interview. Chapin told him, “I need to tell you that you need to record things you care about. You’re not just filling up the world with songs because they’re your originals. You need to write songs about things you care about. And don’t underestimate the song.”

Scott told me, “When I finally recorded ‘Rice Grows,’ it’s a life’s work piece for me. I still play it.”

Standing alone in front of a 1931 National steel guitar he practically stole for $700, a single-stringed diddley bow, an African banjo, and a standard acoustic guitar, he systematically picked each up again and again through two one-hour sets that transported an audience of about 50 to places most of us have never been — colorfully singing about mostly African American experiences that prove the end of slavery was not the end of cultural heartbreak.

Here are some of the topics and lines he sang to the accompaniment of his stringed instruments:

- Turpentine camps that kept blacks in more backbreaking servitude than cotton plantations.

- Malcom X’s assertion that servitude is not as much about the color of your skin as it is what you believe in expressed weeks before he died.

- Getting beaten for destroying a broom to get the wire holding it together to nail to your shack and play like a primitive guitar.

- A song about the country’s most notorious prison, Parchment Farm.

- A proclamation that the diddley bow was where rock and roll started with the artist of the same name.

- Keeping your lamp trimmed and burning as an analogy for how to live.

- Life in the desert surviving on two gallons of water a day.

- “You better come on in my kitchen,” a line David Crosby stole from Robert Johnson

- “Crossroads” as a song about sundown curfews for blacks in the south even in some towns today.

- The 1927 Mississippi flood that had blacks used like sandbags to hold back the river with a Lonnie Johnson song and its incendiary last verse, “Ain’t gonna drown in that river, ain’t gonna break my back.

- “A Change Is Gonna Come,” Sam Cooke’s answer to Dylan’s “Blowin’ In The Wind” with the line “How many years must a people exist before they are free?”

Related: Check out our recent interview with Ainslie in The Robert Johnson Few People Knew.