“All of a sudden, I floor the car to 118 miles per hour. It’s good rock and roll. It’s the same chords as ‘Sweet Virginia’ turned up and down 20 times.”

Marshall Chess is listening to The Rolling Stones’ new album, Hackney Diamonds, with the car stereo turned up to 11. He’s a year older than Keith Richards. The son of Leonard Chess, the founder of Chess Records, Marshall was the producing architect of albums by Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf that introduced them to a mass audience in the late 1960s. Now, he’s produced New Moves, an album that once again expands the blues market by incorporating hip-hop.

Young people in the 1960s were looking for the source of the blues that inspired the British Invasion, and Marshall led the charge. He turned unsweetened ice tea into sweet tea and was the man behind the scene that turned Sticky Fingers into the best album The Stones ever released.

This article is part one of a three-part look at a man who spiked the sweet tea that is today’s blues scene. And he’s got a new release that combines hip-hop with classic blues, but I’m getting ahead of the story.

“My car is seven years old. It has a super good stereo. Now, in the last two weeks I’ve been listening to the new Rolling Stones. Everyone who interviews me asks me if I have heard it. I figure I’d better listen to it. So, I ordered the CD. I’ve been riding around with it.

“I’ve got 45 CDs in my car. I ride around mountain roads. I thought it was a great way to get memories and actually become a fan in a different way of my father and uncle (Chess Records founders Leonard and Phil Chess). I mean, I’m blown away by some of this shit that I always listened to in a different way when I was younger.”

One could argue that the three generations of Chess men collectively have done more to expose blues to the masses than any other individual or label since the invention of recorded music. Now considered America’s contribution to world culture, blues was largely a regional style of the delta promulgated by African Americans who fled from the south to Chicago to escape prejudice and find work, beginning with Muddy Waters in 1945. Together, this generation of blues artists plugged in their electric guitars to be heard in the noisy South and West Side bars.

From the 1920s to the early ‘40s, blues recordings were called “race records” or “R&B” with relatively little appeal to the larger white population.

While labels like Delmark, Cobra, Arhoolie and later Alligator and Rounder met the growing demand for recordings of this music roughly between the early ’50s and beyond, it was Chess Records that created a demand for blues beyond its core audience of African Americans, both rural and urban. Leonard Chess and his brother Phil, Leonard’s son Marshall, and now Marshall’s son Jamar have been in a vanguard of blending the core sound with influences that appeal to a wider mass audience.

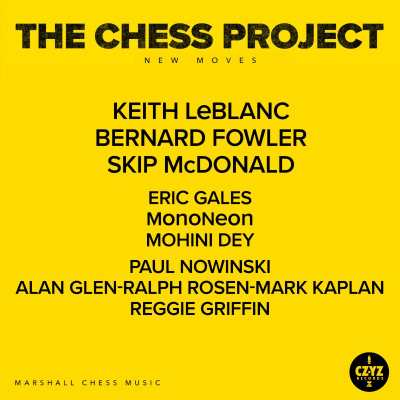

Marshall, now 81 years old, has released a recording that blends hip-hop influences with the electric blues songs of Muddy, Howlin’ Wolf and Sonny Boy Williamson among others. The question is will lightning strike again? Will this new sound once again find favor with a young demographic brought up on the sounds of hip-hop?

“I got a great history, and I’m one of the few left alive to tell it,” says Marshall. “I just love making records, man. It’s the thing I love more than anything. I always tell people the great part of what I do is you have to get used to failure. Most of ’em don’t sell. Most of them disappear. But I love making records. I set up Rolling Stones Records. The tongue and the lips is my baby. I began with them in early ’70 through the end of ’77, almost eight years.

“I’m performing in my own way when I’m making a record. It’s almost like the way early records were made. The producer is more like a movie producer getting a performance like a movie director gets out of actors than what is used today. I used that with the Rolling Stones when I worked on all those albums.

“I noticed, too, that they were very receptive to that style of producing because no one would use it. No one ever learned how to do it. All these young producers are born generations after the early style, and there is no need to learn how to force people to lock together when you have multi-track recording. It doesn’t even enter the mindset.”

Marshall recalls his conversation with Mick Jagger:

Hi, Marshall Chess. I thought you owe me shit! How are you? Oh, my God. I heard about your father dying. Too bad, man.

Mick Jagger

Yeah, man, things are (stressed) I’m no longer with Chess. I’m looking for something new to do. I heard you just got rid of your manager and that your label is over. I think there’s something we could do together. You know I want to get into that rock and roll.

“I had met him in Chicago in ’64, and now it was five years later.

“The Stones knew about Electric Mud because I had done one of their cuts on it, ‘Let’s Spend The Night Together.’ They knew we’d done one of their songs, and they would love me for that, you know. And I love them. They are my favorite rock group. I love them, and so Mick said, ‘Come over to London. We can do something, but I can’t come to Chicago. I’ve just had my passport held. They caught me with drugs in my luggage at the airport.’

“I said, ‘Ok, I’m coming.’ So, two weeks later I went to London and that’s how the deal started. I went and met the whole band. I went over to Keith’s house. I talked to Mick first. He danced while we talked. He danced with me while we talked about making a deal while playing Black Snake Blues, the Clifton Chenier album. I sat on the couch. He was dancing back and forth in front of me. I think he was nervous. I was like a car dealer, and he was like the son of Henry Ford. He made me like the seventh Rolling Stone guy.

“I went to England and began working for them as a consultant. We were checking each other out. I was a Jewish kid from Chicago, and they were rock stars from England. It was two different trips. But it worked very well, and it led into founding Rolling Stone Records.”