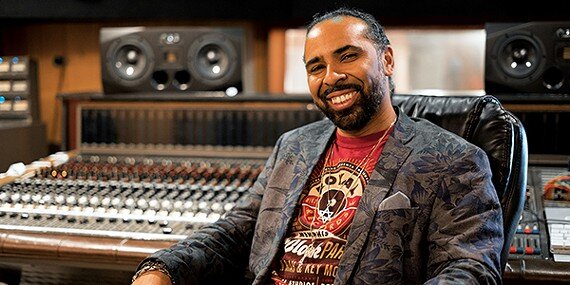

Boo Mitchell has been close to musical royalty his entire life. Growing up in the studio with his father, renowned musician and producer Willie Mitchell, he witnessed the making of some of the greatest albums in soul history, and has grown up to make music history on his own accord. Becoming the first Memphian to win a GRAMMY for Record of The Year in 2016 for his work on Bruno Mars’ “Uptown Funk,” Mitchell has well and truly proved himself to be a master at his craft and his musical affinity extends well beyond the studio.

The producer and musician sat down with American Blues Scene during Blues on Broadbeach to reminisce on his ‘magical musical childhood,’ the meaning of his GRAMMY win, his first paid job at 17 playing for Al Green, his ‘out of body’ experience working on John Mayer’s Continuum album, and more.

You got a chance to get on stage during the festival last night, which isn’t as common for you. How was that?

It was absolutely amazing; the crowd was gorgeous, the stage was beautiful. I mean, it was a perfect ideal concert. Couldn’t have asked for anything more.

What’s your experience like in the studio versus on the stage? Do you have a preference?

I’m normally a studio guy. The stage is fun for me because I like the real time interaction with the crowd. When you’re in the studio and you’re making a record you have to wait to see how people are going to respond to it. But the cool thing about being on stage is it’s real time; you get to see the faces, you get to see the crowd reaction and that energy exchange is unique and inspiring. It feels good to make people happy with your music.

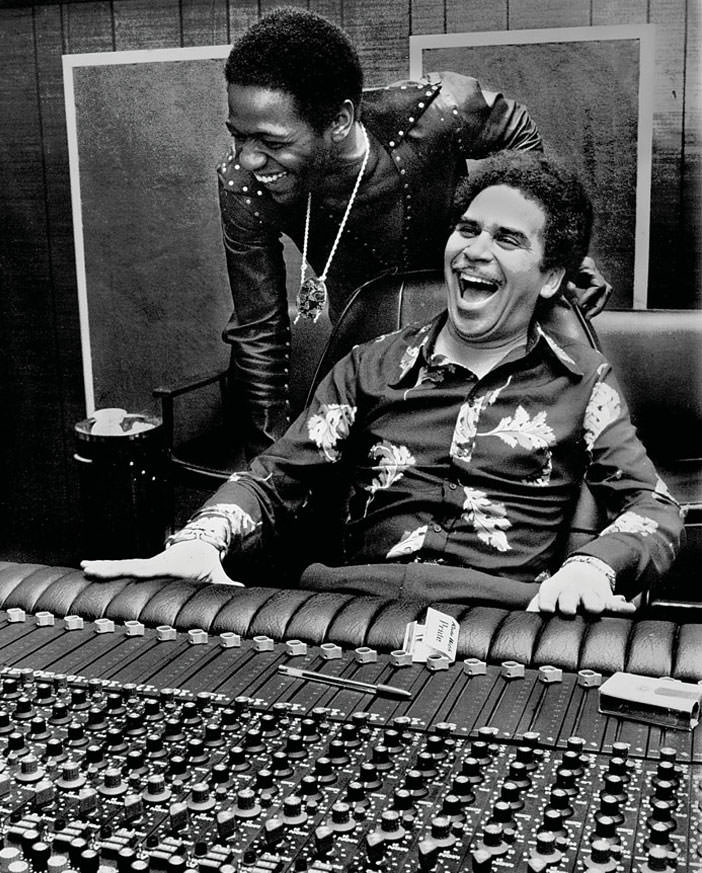

Beautiful. You grew up in the studio watching your dad make records with some of the greatest musicians to ever live. What was that like?

Oh my god, it was crazy because my dad would be recording all these famous people which seemed normal to me at the time, and I didn’t realize it wasn’t normal until I grew up. It still took some time to set in because even after the seventies there was always someone hanging around the house: The Temptations, Keith Richards, The Doobie Brothers, or Al Green.

The older I get the more I’ve grown to appreciate my magical musical childhood, and it’s still happening. We’ve been blessed. Melissa Ethridge – we made a record with her a few years ago and just found out she’s playing at this same festival, so we’ll be going to see her!

A little Australian reunion! So, do you have any special memories of being in the studio that stand out to you?

Absolutely. I remember one day pop was producing Al Green, and the studio just had a magic to it; there was like a smell and a feeling that you got when you walked in. There were a few moments that were pivotal to me coming up as a producer trying to do what my father did. I remember one time he was working on this Al Green record, I Can’t Stop, and the band was playing and pop stopped the tape and said, “Man, this has got a false feeling!”

We were like, “What does that mean?” but I think he was trying to say that the energy wasn’t genuine. The band played it again, and it did. It felt noticeably better. Somebody might have hit a couple of bad notes or something, but he was like, “Alright, this is the take.” And that was a big lesson for me as a young producer, and it was something that I would have to figure out on my own. But had I not seen him do that I definitely wouldn’t be the producer I am today.

That’s amazing. Speaking of the work you’ve done, you’ve worked on some of the most pivotal records of the last two decades. It’s incredible to see your catalogue. I’m interested to know what it was like to work on John Mayer’s Continuum. That was such an integral album for my generation when it came to introducing Millennials and Gen Z to the blues.

I must say that before we worked on that I was a John Mayer fan, but I was a John Mayer guitar fan. I never really focused in on his vocals, but when we recorded ‘I’m Gonna Find Another You’ it started out that he wanted pop to do horn arrangements and he did, and the horn players came in and they sounded amazing. Then John was like, ‘Hey, can we put an organ on it?’ So we called Lester Snell and he put the organ on, and then John’s like “Hey, I want to do a vocal.” I was thinking, ‘Ok, I’m about to record John Mayer singing.’ When he started singing that song, I just had this moment where I went ‘Oh snap, this cat can really sing.’

I never saw him in that light, I always liked his voice, but it didn’t dawn on me that he was a really serious singer so that was this out of body experience watching him do the vocals. We were recording on tape – and people are so stereotypical in their thinking. I’ve heard people say, ‘Oh, that was autotuned.’ But no, I can play them the tape. It’s literally exactly as it is on the record. Plus, Steve Jordan produced that record, and he is the most anti-autotune dude. You know, I already had a tremendous amount of respect for John as a musician but as a vocalist it really changed my perception.

That’s so special. And I just want to go back – obviously Al Green was a big part of your upbringing, and apparently your first paid job was as a keys player on one of his tracks. Tell us about that.

It was crazy! So it was 1988 and pop had just bought me a synthesizer and my brother a drum machine and there’s a little room, an office that’s a writing room by the bathroom. Pop and Al were working on the album upstairs and Al goes to the bathroom and he hears me and my brother jamming. He comes back and he goes, ‘Hey Willie, why don’t we let the boys play on this next tune?’

I didn’t think anything of it. I was 17. I was carrying my stuff upstairs and next thing I know I’m playing synth on an Al Green tune, and I ended up getting paid union scale which was 200 and something bucks. And it was the most money that I had ever made at one time. A few months later it won a GRAMMY. I was 17, so I didn’t really comprehend how big of a deal that was.

Speaking of GRAMMYs, you won one for your work on “Uptown Funk.” Tell me about that whole experience. What does it mean to you to have won a GRAMMY?

That GRAMMY was special because it was for ‘Uptown Funk’ and it was for Record of The Year, which is the last GRAMMY that they give out. To The Recording Academy Record of The Year is the biggest deal GRAMMY. What was so special about that is that there had never been a record made in Memphis to win that GRAMMY, even out of all the albums by Aretha Franklin and Al Green. I’m the first and currently the only Memphian to win a record of the year GRAMMY.

It’s crazy. Dad was nominated for it in ‘72 and didn’t win, just to give you an idea. People were telling me that there were people all over the city in bars watching, so it was a big deal for the city and a big deal for me obviously. But it felt like a big musical win for Memphis.

And you started wearing your dad’s bracelet after you won the GRAMMY?

My dad had given this bracelet to me a couple years before he died, and he passed away in 2010. I just never felt worthy of wearing it, and I only wore it the night of the GRAMMYs because I was trying to get all of the good mojo. I was like, ‘I’m going to channel my Willie Mitchell, Al Green.’ And I wear it every day now. That’s what it took to get me to wear it (laughs). He was so in the house that night. I wore his jacket as well.

That’s such a beautiful story. So, post playing shows around the world, what’s next for Boo Mitchell?

I’m working on lots of records. I’m finishing Mississippi Mcdonald’s album which will probably be done in a few weeks. I just finished a Southern Avenue record with John Bourke, and this new record is really good! They’ve been writing and working hard, so I’m excited about that.