Drawing on years of interviews and eyewitness accounts, Down On The Corner: Adventures in Busking and Street Music – due out November 12, 2024 from Jawbone Press – explores street singers in a myriad of musical genres, from folk to rock ’n’ roll, blues to bluegrass, doo-wop to indie rock. He also surveys busking hotspots – New Orleans’ French Quarter, Chicago’s Maxwell Street, New York’s Washington Square, San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf and London’s Tube, to name a few.

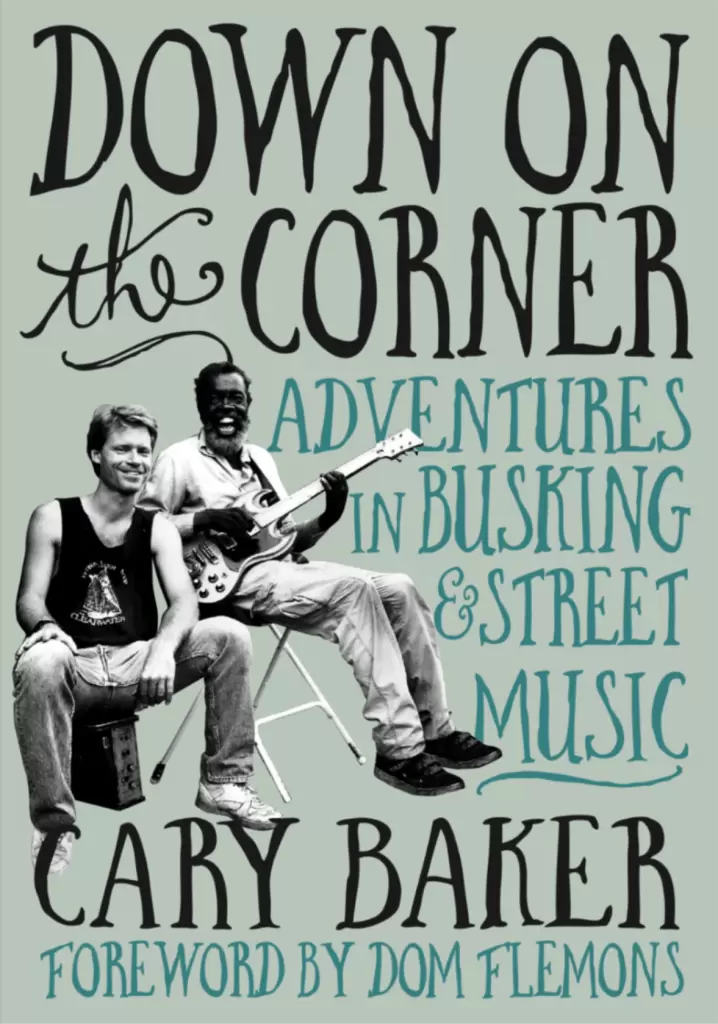

For the first time, veteran journalist and music industry publicist Cary Baker tells the complete history of these musicians and the music they play, from tin cups and toonies to QR codes and PayPal.

He shares exclusively with American Blues Scene his chapter on singer-songwriter Fantastic Negrito below:

For Fantastic Negrito, stage name for Xavier Amin Dphrepaulezz, 1993 began as a promising year. Under the name Xavier, he was signed to a reported $1 million contract to Interscope Records by the label’s founding chairman, Jimmy Iovine, releasing his debut album titled The X Factor under the nom de guerre Xavier three years later in 1996. Interscope was the hottest label of the day, home of multi-platinum-certified hits by Eminem, Dr. Dre, Nine Inch Nails, U2, No Doubt and Enrique Iglasias. Interscope sales accounted for nearly one-third of Universal Music Group‘s 27% share of the U.S. music market.1

The album failed to launch Dphrepaulezz’s career. But that was hardly the worst news. On Thanksgiving 1999, the artist found himself in a near-fatal car crash which left him comatose for three weeks, affecting his ability to play guitar. “I fishtailed and rolled over four lanes of traffic,” he told the Guardian.2 He was 31 years old. The accident left his arms and legs badly fractured.

“And then I stopped,” he says. “I got out of doing all that which I did with touring and trying to be famous back then. I went back home to Oakland, Calif. and quit. I sold everything and became a marijuana farmer with no interest in playing.

“I think that when I stopped wanting it, I just said to myself: ‘You know what I think. I’d like to just play on the street because it feels very good.’ It wasn’t for money. It wasn’t for anything… I thought it was over. I was like, ‘I’ll never pursue that again.’ Not that I just want to play on the street because it felt very honest and beautiful and therapeutic and fun.”

So for the artist who’d soon be known as Fantastic Negrito, busking was not a first step. It was a way to restore a sense of purpose following a disastrous major label experience and a debilitating accident.

It was also a chance for the artist to re-think his musical direction. If the Xavier album hearkened to Prince with hiphop inflections, Dphrepaulezz reconnected with his earliest influences, which he describes as “Southern music and, you know, the black roots. Country blues artists as well.

“I forgot about [trying to make it]. I got into this music because I really enjoyed it. And it was lots of fun and gave me satisfaction, but I didn’t want to chase the whole fame and record deals anymore, just wanted to really connect on the streets with people trying to make it home from work,” he says.

Dphrepaulezz could be found playing music in front of Oakland’s Colonial Donuts in the city’s Lakeshore district. Sometimes he’d cross the Bay and play at San Francisco’s Powell Center, or at 25th & Mission in the city’s Mission District. It almost didn’t matter where he made camp. “I was just playing, because I just love being out there,” he recalls. “There’s a lot of power not caring. not wanting things, and that’s how busking was for me. I just I was just really feeling life.”

During that time, he adopted the name Fantastic Negrito. “[The name] made some people uncomfortable – and that made it even better,” he proclaims defiantly.

His long recovery from the accident and his early days of busking gave him time to gather perspective on his major label experience “I’d spent my entire life, my 20s and 30s, chasing this thing that I could never get. Now I was a guy in his mid-40s. I wasn’t chasing anything. And I wasn’t yet aware of how powerful that would become. And how it’s powerful now to keep reminding yourself: Don’t chase this stuff – be very true to the spiritual side of it.”

So Fantastic Negrito had taken to busking as a midlife antidote to the starmaker machinery to which he’d been a party in his 20s.

“Being a grown-ass man [on the streets], there’s a complete opposite side of the spectrum to how you’re approaching an instrument or playing. Or that you have to really connect with these people who don’t care about you playing out there. And there’s something very powerful about that every day to know that. These people [on the streets] don’t even care about what you’re doing. And if you can connect with them, that’s very powerful.”

Sadly, not all of his friends and family saw it that way. “I knew some people who were a little embarrassed for me,” he shares.

“And I remember there some women from Saudi Arabia that used to come to hear me secretly,” he says, “They’d sit there. They didn’t want anyone to know that they were there. That was something that I really never forgot; these women from Saudi Arabia were so transfixed with what I was doing. And they’d sit there, admiring what I was doing. But they were like, ‘No one can know that we saw this.’”

One day a street observer suggested that Fantastic Negrito enter the NPR Tiny Desk Contest. He submitted a video and – against all odds – became the prestigious annual contest’s first winner in 2015.

At first he’d been reluctant to enter: “I just kept doing it [on the streets], having fun. I think that was the key. I wasn’t looking for any of this when someone asked me, ‘Do I want to participate in Tiny Desk?’ And I was like, I said, ‘No, actually.’ I just had no interest. I didn’t think what I was doing really matched with NPR was about either. I had a lot of feelings about that, and finally I was talked into it, and I did a one take performance that beat 7,000 people – which I’m still in shock about.”

Tiny Desk was the start of what became an organic second music career for Fantastic Negrito. He won his first GRAMMY Award in 2017, when The Last Days of Oakland received Best Contemporary Blues Album. He won again with its follow-up, Please Don’t Be Dead, which won in the same category in the 2019. His third GRAMMY in that category was awarded in 2021 for his album Have You Lost Your Mind Yet?

Needless to say, Fantastic Negrito has since then toured the world, playing ticketed shows in respected indoor venues. But he continues to busk every opportunity he can.

“I definitely still do it,” he says, “especially in places where I’m not known. Like I was in Japan for a month [in 2023], where I was playing always on the streets. I just sneak around to the little places where I can go… at like 3 in the morning to some places.

“Whenever I can do it, I do it. It’s like one of the most honest moments you can have.”

About the author: Cary Baker is a writer based in the Southern California desert. Born on Chicago’s South Side, he began his writing career at age 16 with an on-spec feature about Chicago street singer Blind Arvella Gray for the Chicago Reader. His return to writing follows a 42-year hiatus during which Baker, by 1984 based in Los Angeles, directed publicity for six labels (including Capitol and I.R.S.) and two of his own companies, working with acclaimed artists and labels such as R.E.M., Bonnie Raitt, the Smithereens, James McMurtry, the Mavericks, Bobby Rush, Willie Nile, and Omnivore Recordings. Prior to his PR years, Baker wrote for the Chicago Reader, Creem, Trouser Press, Bomp!, Goldmine, Billboard, Mix, Illinois Entertainer, and Record magazine.

He has also produced and/or written liner notes for historical reissues from Universal, Capitol-EMI, Numero Group and Omnivore. He has been a voting member of the Recording Academy since 1979.

Down on the Corner: Adventures in Busking and Street Music is available for pre-order here.