Seeing John Hammond live at Club 47 in Harvard Square in 1964 fundamentally changed my view of music for the next 60 years. He’d just released his first album on Vanguard Records, at the time the premier label documenting the burgeoning folk revival. To my friends Bill Nowlin and Ken Irwin who would later found Rounder Records, blues was a subcategory of a genre that included bluegrass, protest music and the hootenanny styles of people like Dylan and Tom Paxton.

Delta blues was a totally separate acoustic regional African-American music that at best was a footnote to that revival. Chicago blues was electric and was influencing British Invasion acts like The Rolling Stones and The Animals, but Delta blues artists like Son House and the late Robert Johnson were virtually unknown to the masses on college campuses who identified with the lyrics of Dylan, Tom Paxton and Dave Van Ronk.

John Hammond grew up with his mother, a matriarch of the culturally elite Vanderbilt family at the extreme opposite end of the American melting pot from the Delta blues artists. However, his father John Hammond Jr. (John has a different middle name) was an A&R executive at Columbia Records who discovered Billie Holiday, was the first to present African-American blues to a white audience at Carnegie Hall in 1938, and was Jackie Robinson’s golf buddy.

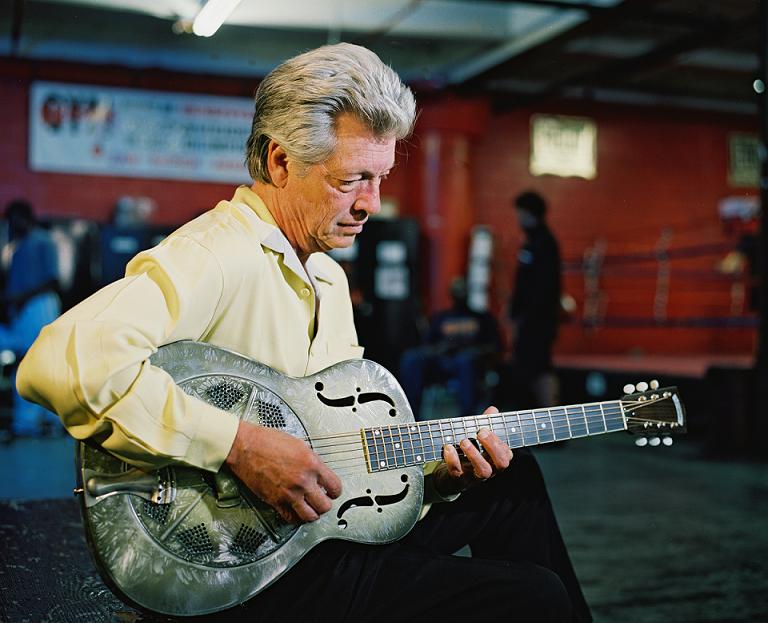

The young John was 21 and had only been singing Delta blues and playing acoustic guitar for three years when I saw him in 1964. Here was an upper crust white kid playing the blackest music I’d ever heard.

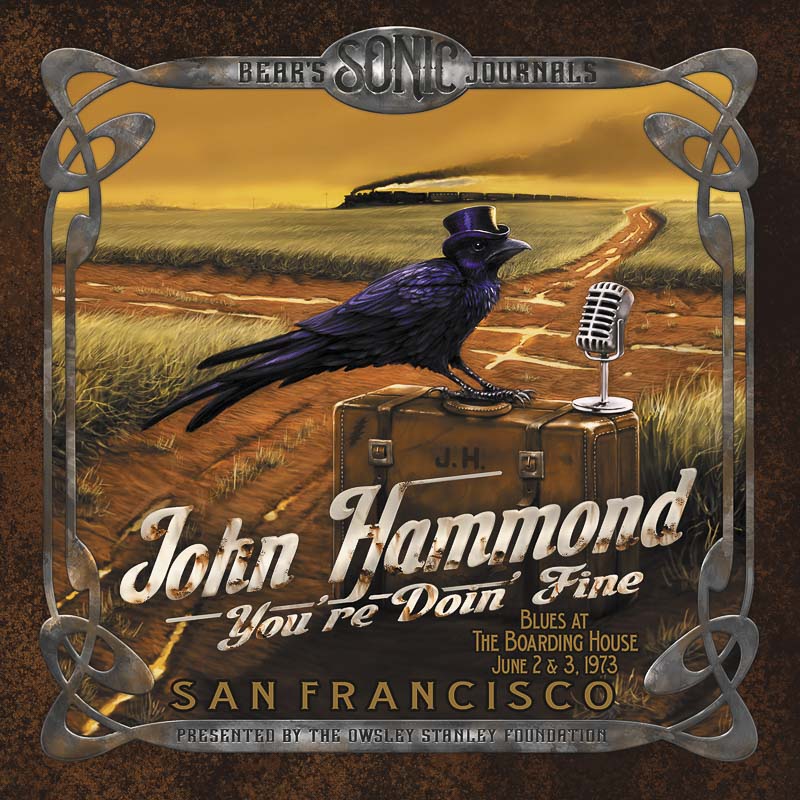

Fast forward to 2024. The Owsley Stanley Foundation of Grateful Dead fame has just released You’re Doin’ Fine, a sumptuous three-CD set capturing John Hammond at two 1973 concerts at the Boarding House, a small club in San Francisco. The sound man was Owsley Stanley who invented the Grateful Dead’s wall of sound technology. There are 43 songs featuring John Hammond alone on acoustic resonator guitar and vocals covering Delta blues treasures like “Look On Yonder’s Wall,” “Shake for Me,” and “Rag Mama.”

Now 81 years old, John looks back on a career that for the most part stayed focused on acoustic blues. “I was a blues fanatic going way back even before I had a guitar or even thought about it. I had some really good records, and I just loved the music. When I got my guitar, I was already 17, 18 and knew exactly what I wanted to do, and I just went for it.”

John Hammond would go on to rise above the caricatures of his mentors (by artists like Eric Clapton, Mick Jagger, and Eric Burdon). He was and is the alter ego representation of a culture as alien to his ethnic background as any in blues.

Here are edited portions of my interview with John.

The two gigs you did at The Boarding House included on this album about to be released includes John Waits and John Lee Hooker in the audience. Is that right?

That’s right. Tom opened the show for me.

Had you known him?

No, that’s when I met him.

Really!

Yup.

You did some stuff with him later on. That relationship has gone on for decades, right?

That’s correct. The album that he produced for me has sold more than anything I ever did. It’s called Wicked Grin.

Yeah, that’s a great album.

He’s an amazing guy, and it turns out he’s a great fan.

Well, who isn’t? You changed my life. You were the guy. I was into the Stones at that point in time, and I’d been into rock and roll, but going into Club 47, I have the distinct memory of how you knocked it out of the park. And I remember thinking, this guy is just starting out, and he’s this good!

Well, you flatter me.

Well, you deserve it. How significant were those two shows on the album to your development? Why did you pick those two to release now?

I didn’t pick ’em. They were picked by the Owsley family. I didn’t know that Owsley was recording that show. I was told he was the sound man, but I didn’t understand the significance of it. I mean the sound is great.

You didn’t understand or know the background that he had really developed a more contemporary sound for the Grateful Dead than any of the other rock bands of that era?

I did not know that. It was just a guy for me. It was exciting and fun. I enjoyed all my gigs. It was a good crowd and The Boarding House was a place I’d played before and went on to play again. So, it was a good venue.

How did that happen? Did they come to you and say,“We want to do this expanded focus on you that’s gonna be more intense than you’re ever had in your career?”

Exactly. I had no idea it was gonna be that extensive, but I knew they were excited. You know, the way I found out about it was they sent me a project they had worked on with Doc Watson. The sound was so good, and it was just a great recording, and it hooked me. I said, “Gee, that’s great,” and they said, “Well, we have this stuff on you at The Boarding House way back, and we think this is gonna be our blues thing.”

And I was mystified. I wasn’t aware of that show. I mean I was aware of having played that show but not that it had been recorded or whatever. So, I was just blown away when they came up with this seriousness about it. You know, making a big package about it. I was amazed about it.

In retrospect, do you think they picked two nights that were particularly powerful from that era?

I guess they did. I didn’t play a lot of venues where Owsley had done the sound. So that was one they thought was great.

Did you recognize when you were doing the shows that the sound was special because he was like at least a decade ahead of everybody else in terms of capturing the sound of the artist in a way that made what the audience hear the same thing that you heard when you were performing? Did you get that?

I was aware that the sound was great in the room. The sound guy who it turned out was Owsley was very receptive to what I wanted as a sound, and it was just a great night.

The album is just a beautiful package.

Yeah, I mean I’m just blown away.

I think what I love about it the most is it’s a package that lives up to who you are, and it way surpasses what anyone would expect this late in your career. You’re not Eric Clapton. You’re not somebody who is a major success, and yet this album is an incredible package.

Yeah, I think so, too. I feel very gratified. They said they were gonna do something big and they did. For this to be as good as it is I’m very gratified.

You told me in the 1970s that your dad recommended you not become a musician because the money wasn’t so good. What do you think he’d say now if he were alive?

(Chuckle) I don’t know.

Why are you chuckling?

About the money. He just said it’s a rough business, and I think he was worried that I’d be depressed or something and not make it.

In reading the liner notes here I’ve read a lot about your dad, but I learned a lot more. Apparently, he was prescient in terms of the relationship between black and white in the genre. I think if he were still alive, he’d be very proud of your heritage and what you’ve done.

Well, I would hope so. I mean I worked really hard to make things right the way I thought, and I’ve had a great career.

You were an anomaly for Vanguard at that point in time, weren’t you? They were doing mostly folk stuff.

I was their first blues guy, and then after me came a whole project with Sam Charter and the Chicago Blues, Charlie Musselwhite.

Tell me that story.

Well, in 1963, I was familiar with these guys in Toronto, Levon (Helm) and the Hawks. (Note: They became The Band.) They used to come to my shows in Toronto when I played up there, and I went to their shows when they came down to New York and New Jersey. And so, we were friends, and I used to sit in with them all the time. We had fun.

They were in New York a while trying to get a demo record together, and it wasn’t going well, and I said, “Well, I’m signed to Vanguard Records. Let’s make a record together,” and they said, “Oh, yeah. Let’s do it.” So, that week Michael Bloomfield and Charlie Musselwhite were in town and I invited them to the session. We had one day to make the record (So Many Roads).

You told me 50 years ago it was the acoustic stuff that you were more proud of. Do you still feel that way?

Yeah. I had some fun making electric records, but I always felt that my strength was within the solo acoustic.

Had you heard of those concert recordings before you made this record lately or did that come as a surprise, and what was your take on hearing it again?

You mean the album that’s out now?

Yeah, the new one.

Yeah, I had not heard before or even thought of it. When I heard it, I was amazed, you know, that the record was that good.

Understand that by my hanging out with Bill Nowlin and Ken Irwin back in 1963, authentic was the name of their game. And what I found out about you was you were authentic but white. I didn’t feel you were copying the people you were emulating. I felt like you were inspired by them, and you added your own magic sauce to the mix.

Well, that’s what singers do. You take songs you like, and you make them your own, and that’s what my whole thing was about. I love to play and would love to sing – and I have to play for audiences, you know, and for me it was terrific to start with. It was just one of those things. I just knew at this stage of my career, “yikes.” I went on to do other things. I had some great recordings. So, I don’t feel bad.

I don’t think there are many white singers that black artists have imitated. Have you ever had an African-American artist say to you that he was influenced by you?

I guess I’ve been and was with guys who said, “Wow, I’ve been inspired by your playing.” I mean Taj Mahal once said to me, “We’re very deep into it, and (you) are very inspirational to me,” and I was amazed because he’s great, and I’ve been on shows with Alvin Hart, and he’s said he was inspired with me and so forth, but I mean I don’t know that I’ve been that influential to other artists, but I just love what I do.

Do you want to take a shot at what the secret sauce is that makes your career in the delta blues authentic whereas most white artists are merely copying the originals?

I don’t know how to articulate the sense of feeling. I’m so passionate about the songs, I just feel like I’m part of the mix of the songs.

You’re way more than that. I’d been listening to the Stones and the British Invasion cats and Haight Ashbury. I hadn’t started yet, but when I heard you, I said this is my sweet spot. You were it, and I’ve never changed my mind. Sixty-one years later I’ve never changed my mind.

Wow.

Do you remember those early gigs at Club 47?

I remember Club 47 so well, One Mount Auburn St. I remember all the characters that hung out there. I became good friends with Jim Kweskin. That’s when Taj Mahal was Henry Fredericks.

If your dad were alive today and you had a chance to spend an hour with him, what’s the most important thing you’d tell him about what’s happened?

I’ve done so much more than I thought I would do in terms of being acknowledged by the blues community and that type of thing. I’m a very happy guy. I’d like to talk to him about these little takes on this and that, but I don’t know how much I could tell him.

Give me one example.

Well, what he would think about how American music has changed or what kind of flow and direction it’s in now… When Covid hit, and I had all of these guys lined up, it all fell apart. It was time to re-examine where I was going and I played so many gigs, and my wife and I were saying, “Maybe it’s time to hang it up, you know?

Please don’t.

No. I’m still there. I’ve played so many gigs like you who’ve written so many articles. I’ve played all these gigs. It’s fun to look back.