Lilli Lewis has spent years igniting critical conversations within the music industry. As the singer-songwriter, composer, and visionary behind the Black American Music Summit (BAMS), she is now fulfilling the latest chapter in her lifelong mission to create spaces that amplify Black voices, celebrate the depth of Black musical history, and challenge the ways it has long been marginalized. This latest chapter was originally catalyzed by the reckoning following the tragic death of George Floyd in 2020, and what began as a response to a single act of racial violence evolved into an ongoing dialogue and cultural shift.

In the wake of the unrest, Lilli reached out to Aengus Finnan, then Executive Director of Folk Alliance International, with a proposal to support the Folk Alliance community in processing the emotional turmoil. The proposal was approved, and Treasa Levasseur, the Programming Director at the time, named the program Committing to Conversation. Treasa also brought in Korean-Canadian artist Janice Jo Lee (now DEIA Coordinator) and singer-songwriter SaulPaul to help facilitate the sessions. The facilitators rotated, each bringing their unique perspective to the conversations. “Folk Alliance seemed like an obvious partner because they had a belief in justice and equity, bringing that sense of justice to their community at large. But after a couple of years, I realized this was work geared towards the white gaze. It wouldn’t make a difference until they experienced us in numbers, because they’re used to picking one or two Black individuals and leaving the rest out of the story.”

“The Black American Music Summit is where I’m putting all my energy right now,” she says, her voice radiating resolve. The experience of belonging at FAI was especially important to Lilli, because “people were coming to Folk Alliance to build their careers, but Black Americans were being left out of that ecosystem. Some artists didn’t even know they had a place in the genre.”

After nearly a year of Committing to Conversation sessions, Lilli realized the need to develop something larger: a summit. “Something where the [Folk community] can experience what it feels like to have [Black folks] around in numbers. The way the room responds in the BAMS showcase room is different. There’s a magic that happens and parts of ourselves – that don’t always get to show up in folk and Americana spaces – that come out naturally when there are more of us in the room. (At Folk Alliance) you feel like you’re in an authentic space where the focus is on the music, not the vanity aspect. I just wanted more people who might have shared my story to feel welcome.”

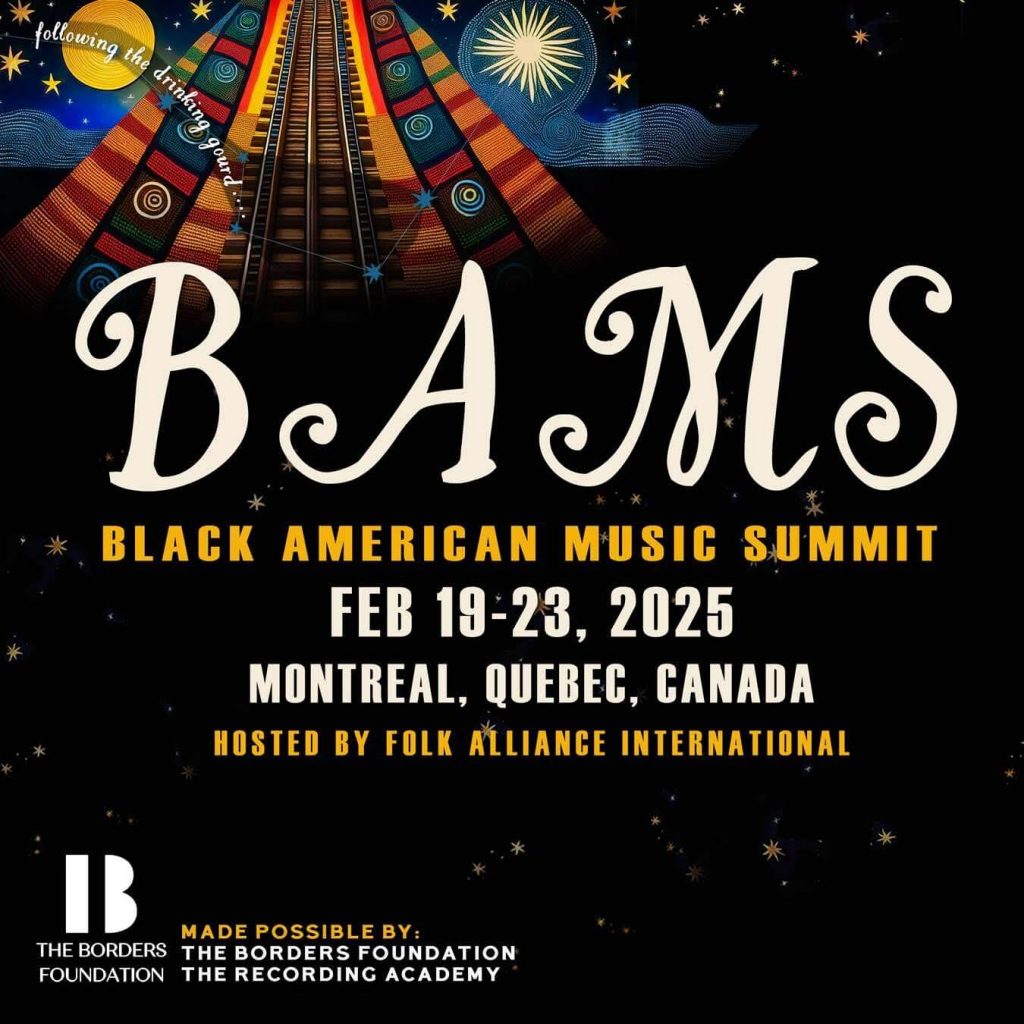

The idea was partly inspired by Lilli’s experience at the Indigenous Summit during the 2019 Folk Alliance conference in Montreal. The energy of the event left a lasting impression, as she felt the strong presence of the Indigenous community and a deep respect for their culture. This experience inspired her to establish a similar space for Black voices. Lilli proposed the summit, and it too was approved. She consulted with other Black members of the community to gauge their interest, and it was one early ally Paula Boggs, a decorated attorney turned Americana artist, who ultimately named the summit “BAMS,” which officially launched at the Kansas City FAI Conference in 2023.

Lilli spent the better part of the rest of that year on the road, even opening five dates for childhood heroes the Indigo Girls, but late in that year, she was diagnosed with end stage renal disease. That diagnosis opened the door to asking people who had participated in the event before and others to help evolve it in her stead – embodying a level of perseverance, nobility, and selflessness that moves me deeply. “I put others out front for a while, thinking I could step back, but it turned out the project needed me as much as I needed it. What makes me keep coming back are the responses from the participants—people saying they never thought they’d feel like they belonged in that environment. The feedback shows people come back for BAMS because they can take up space and be themselves, without feeling like they’re constantly auditioning. It’s also creating opportunities for people. A lot of people who came because of BAMs are now doing official showcases, collaborations, or have gotten booked for major events like Kerrville Folk Festival.”

The limitations on how Black Americans are seen within the folk and Americana spaces reflect a larger issue that Lilli and I discussed during our 2021 interview about her album, aptly titled Americana. People already made up their minds about what the genre means before even listening to the album. Not what it means to me or you, but to them. “Right. Not what it means to me. And also, even if I was singing in a genre that was consistent with what it means to them, they still wouldn’t hear it from me. Last year, someone reviewed All Is Forgiven, saying it was almost painful to listen to because I carried the entire story of American history in my voice. On the one hand, that’s powerful, but on the other hand, they juxtaposed it with a band described as ‘unbearably white’ and said their music was ‘easy to listen to.’” What this points to, she explains, is marketability. Much like the movement of tectonic plates shaping the Earth’s surface over time, there is a force at play that whispers subliminally in one’s ear that Black American voices will make you sad while others are perceived as more enjoyable. “When do we start just talking about the music?”

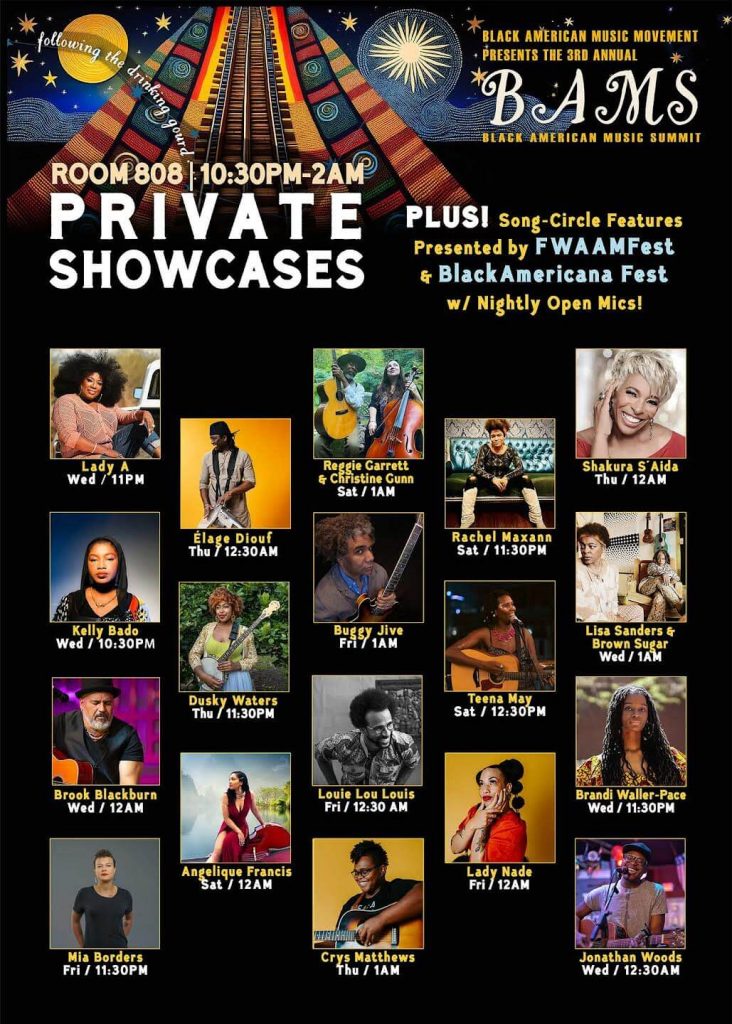

I expressed to Lilli that while the heart of activist folk still pulses through certain musicians, like BAMS showcase artist Crys Matthews, its resistance spirit has become less central in the broader contemporary folk scene. “I believe that was part of a deliberate effort to smudge the reputation of anybody using their art to speak truth to power…speaking truth to power is deemed anti-American.” And that’s just one part; the other issue was folk music becoming a commercial commodity. “You had these incredible artists like Joni Mitchell, James Taylor… And all of a sudden, this music is making money.”

If you were to ask her, Lilli would say our society isn’t structured for us to have many truly shared experiences in the face of the American construct of race. But one of the things she loves about the folk community is that, if you’re willing to reconnect with Black folk/roots music and recognize that they’ve always been both innovators and keepers of tradition, then you can tap into a shared cultural heritage through music. “It’s undeniable when you’re in the room with it.” Yet, as she points out, “At Folk Alliance, you can have an artist playing the blues with no problem. But if it’s a Black blues artist, all of a sudden, it’s just blues and not folk anymore. Dude, blues music is folk music!”

Just look at Lead Belly and tell me where blues ends and folk begins. As an artist and advocate, how does she navigate these complexities? As an artist, she tries to ignore it. Her job is to speak and sing from the heart and to create experiences that connect with people. And as an advocate? “I’m a middle child, always trying to fill in the gaps. If I see a hole, I want to fill it. My voice is not the voice for wallowing in pain, but I think it is connected to a universal strand of grace. In my advocacy, I don’t mince words; there’s a lot of repair work that needs to be done, and I can’t do that by being Pollyanna about it. As an artist, I want to facilitate a shared experience. On stage, we’re already halfway there; it’s about sharing the beauty of the moment together. The win is never so clear as when we’re in space together enjoying music.”

BAMS builds its summit theme around that of the larger conference, which is “Illumination” this year. BAMS’ approach to this theme is “Following the Drinking Gourd,” inspired by the Black American folk song associated with the Underground Railroad and achieving one’s freedom. “We talk about following one’s creative vision, that point of contact with the muse, the light that comes when a new creative idea arrives. The illumination makes you follow your intuition that a new creation or new life is possible. It’s no small matter. For [Black Americans], that illumination has meant the difference between life and death. This is especially relevant this year since the conference is in Canada, where so many of us escaped to. In honor and recognition of this, we do have two opportunities for Black Canadian panelists to share their experience and history.”

This theme is profoundly connected to her own creative process. For Lilli, 19th-century spirituals are still modern music—spirituals filled with messages of grief and resilience, themes that continue to resonate in the songs she sings today. “I’ve always felt that I’ve been trying to follow the drinking gourd, trying to get free. And that’s always in my music, but even though I haven’t been as explicit about it in recent years, the tradition is alive, and I’m still following the North Star. That symbology is life and death, torture vs. sovereignty, keeping your own kids…”

Lilli’s reflection on Black trauma speaks to a deeper evolutionary instinct. In the face of domestic terror and systemic oppression, subtle methods of communication – like quilts, braids, and music – were developed as a form of survival. “This obscuring of language became second nature, and it’s why we’re metaphorical artists today. Every thought, word, and deed was policed. That forced us to obscure everything. And this is something other Americans don’t have to contend with. Discrimination is one thing, but living with constant surveillance and repression is another. My great grandfather, Rev. Dr. William J. Faulkner taught how we had to pretend we weren’t talking about people, how we made up a whole coded way of talking about animals because if the master overheard, we’d be punished.”

Joel Chandler Harris, author best known for his Uncle Remus stories, is a prime example of how these stories were preserved while also being domesticated, downplayed, and decontextualized of their original meanings. Harris capitalized on the co-opting and distorting of rich, complex folklore passed down by enslaved Black people, without the awareness of the messages they carried. “This may have led wider audiences to see Black people as simple-minded, but we knew better. This same tradition of coded language is embedded in Black art from blues to bebop to Kendrick Lamar.”

So how can the Black American Music Summit address the challenges facing Black musicians within the white folk community today? “Well, part of it is exposure. Part of it is just encouraging us Black Americans to take up more space in that environment. I personally believe that the more space we take up, the more chance we have for this to be organically healed and not just a perceived movement. That’s the opposite of what I’m trying to do. This is not a coarse DEI gesture, that’s not the point. Another thing is putting them in the room with the talent buyers, the people who are there to do business. It’s a very dynamic environment when it comes to doing business. People book out their festivals, their calendar years, their concert series… That stuff gets scouted at Folk Alliance. Not only does BAMS give exposure to Black artists, but it also hopefully puts more money in their pockets, and money means equity.

“The third thing I think might be unique to this specific iteration of the conference is that we’re trying to give them a chance to hear conversations they wouldn’t normally hear. For example, one of the conversations will be about DEI: ‘Is DEI dead?’ We have Ann Powers from All Songs Considered (NPR) to help lead that discussion. We want folks to hear conversations from people who are on the ground, in the meetings, hearing how things shift and how they have to pivot when the corporate and governmental structures stop paying attention to important issues. I want artists to get access to perspectives that they wouldn’t normally have. So, I guess it’s all about access: access to the space, access to the people, access to the conversations. And access to each other. If we take the equity letter seriously, we could also be creating opportunities for each other. That’s another one of the panels: people who’ve created festivals to do what I’m trying to do with the summit. But we need more writers, talent buyers, agents, and managers in the field. Obviously, BAMS can’t do it all, but we can touch on it all as the program keeps growing.”

Indeed the Summit has grown enough that they created a parent organization, the Black American Music Movement, for which this year’s BAMS co-producer, Bertrand Evans-Taylor, has been appointed Executive Director. “This movement connects the dots in American music history, bringing Black people into the fold of narratives we have been extracted from. We’re incubating in the folk, Americana, and country spaces, and also embracing rock, punk, EDM, and DJ spaces—places where people forget that these were Black traditions that evolved into what they are today.

“There are people in the current folk community who don’t have trouble taking up space, who know they have a seat at the table. Shakura S’Aida, who will be leading a workshop on authentic artistry, is a great example of how to just that.” ABS’s Don Wilcock wrote in an interview, “Shakura S’Aida is a great blues artist whose resume is like no other in the field. This Toronto native’s credentials include acting roles in TV shows like Schitt’s Creek and Batwoman… (She) is mesmerizing on stage. I once introduced her at the Pocono Blues Festival and watched her prepare for her appearance like a runner determined to win an impending marathon.”

Lilli continues, “Shakura was the reason I dug in with Folk Alliance. When I first attended the 2019 Montreal Conference, I got on the elevator and she immediately embraced me. She made me feel so welcome, always acknowledging me in a very genuine way. That one person made me feel like I should come back, like there was something here for me. Not only did I find community, but I found meaningful work with the conference. One person can make a big difference.”

Lilli’s dedication to providing access to voices and stories often overlooked is not just evident in her work with the Black American Music Summit but also her new foray into children’s literature. The book, now written and awaiting illustration, is about Lilli’s love of pianos and where that has taken her.

“Little Lilli loved pianos,” reads the first line of the flagship offering in a new children’s book series by Black Girls Love Press. The series features unique interests (e.g. music, computers, science, math, animals, photography) among young girls in order to encourage children to follow their dreams. Often, young Black girls are overlooked in many of these fields, and this series seeks to spark their imaginations.

All of the characters are based on real people from or living in the Greater New Orleans area, with Lilli as the focus of the first installment. “The Threadhead Cultural Foundation awarded us a grant to help this dream come to fruition. I couldn’t be more honored to be a part of this project. I’m having such a good time with Little Lilli that I want to send her on all kinds of adventures.”