Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson lost their lives in a plane crash in the early morning hours of February 3, 1959 after a performance at the Surf Ballroom in Cedar Lake, Iowa. Twenty-one year old pilot Roger Peterson also died in the crash.

The crash was big news for a short time but as always happens with news stories interest faded and other headlines took its place. Don McLean’s “American Pie” brought it back to the public consciousness in the early 1970s. Interest in the tragedy and the stars who died was heightened with the release of the films The Buddy Holly Story in 1978 and 1987’s La Bamba.

But for those close to Buddy, Ritchie, J.P., and Roger, coping with the tragedy was not easy.

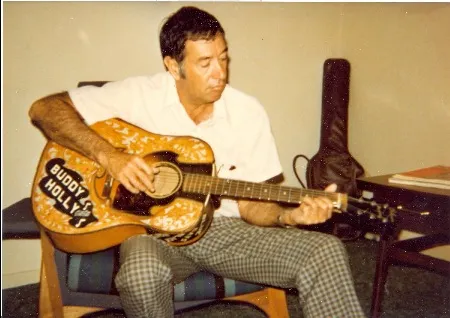

Larry Holley, Buddy’s older brother, was tasked with traveling to Iowa to identify Buddy’s remains. Buddy was named Charles Hardin Holley at birth. He was always known as Buddy, though, and when his last name was misspelled on a record contract, he decided to keep it. Larry and Buddy were close, so close Larry sometimes thought of his much younger brother as a son. Larry lost all interest in music for a good ten years afterward.

The Crickets, Jerry Allison and J.B. Mauldin, had parted ways with Buddy in October 1958 to continue working close to home and with Norman Petty. They wanted to rejoin Buddy in Moorhead, MN, or some stop thereafter. They called Maria Elena Holly first and then the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa but were unable to reach them. Tommy Allsup recalled Buddy talking to him about a reunion with the Crickets for a European tour.

Maria Elena Holly suffered a miscarriage just two days after Buddy’s death. The stress and anguish of losing her husband was considered to be the cause. Maria Elena did not attend Buddy’s funeral and to this day has not been to his gravesite. She has worked to keep Buddy’s music and memory alive, however.

The final words exchanged between Waylon Jennings and Buddy Holly were “I hope your ol’ bus freezes up” by Buddy and Waylon’s comeback of “Well, I hope your ol’ plane crashes.” The words were spoken in jest, two friends engaging in good-natured humor. Still, Waylon was haunted by his words for the rest of his life.

Tommy Allsup told the story about his coin flip with Ritchie Valens countless times over the years. He would choke up nearly every time he told it. When I spoke to him in 2010 he was still wondering why he agreed to that coin flip after refusing several of Ritchie’s pleas to “Let me ride!”

I also met Ritchie’s siblings in 2010 at a recreation of a 1959 Winter Dance Party Tour show in Watsonville, CA. The family moved there not long after Ritchie’s death. The house Ritchie bought for his mother in Pacoima held too many bitter memories. The family – older brother Bob, sisters Connie and Irma, and younger brother Mario – have worked to keep their brother’s music and memory alive. But when the subject of doing a story about his last tour was broached, they grew uncomfortable. As Irma put it, “It would mean reliving it all over again.” And reliving it was something they would not be looking forward to.

Jay P. Richardson aka The Big Bopper, Jr. was born in April 1959, nearly three months after his father, J.P. Richardson aka The Big Bopper, died. His mother remarried and Jay grew up knowing who his father was but with no pictures or other memorabilia in the house. He followed in his father’s footsteps as much to connect with him as to keep his memory alive.

When he died, the Big Bopper had only $8 in a savings account and his most valuable assets were a $400 Dodge sedan and a $100 guitar. He had not yet received the royalties from his million-selling hit, “Chantilly Lace.”

* * * * *

The music industry, and rock and roll in particular, has suffered many tragic deaths since that day in February 1959. But rock and roll was in its infancy at the time and its stars were in their youth. As Steppenwolf would later declare in “Born To Be Wild” it was a time when youth felt they could “climb so high” and “never want to die.” That notion came crashing down to earth that day along with the plane carrying Buddy, Ritchie, J.P., and pilot Roger Peterson.

Furthermore, rock was also reeling from payola scandals involving pioneering DJs Alan Freed and Dick Clark. The King of Rock and Roll, Elvis Presley, had been drafted into the Army and thus not available to go on tour. Little Richard had forsaken rock to seek salvation in gospel music. Jerry Lee Lewis, the Killer, was being ostracized for marrying his teenage cousin. It seemed like rock was over. Of course, it wasn’t thanks to four mop-topped lads from Liverpool, England. But they would not arrive on the music scene for nearly half a decade.

In a short series such as this one it is impossible to provide all the details with respect to the 1959 Winter Dance Party. For those who are interested in learning more about this event and the people who were part of it, I recommend the following:

- Rave On, The Biography Of Buddy Holly (1996) by Phillip Norman

- Ritchie Valens, The First Latino Rocker (1987) by Beverly Manheim

- The Day The Music Died (1997) by Larry Lehmer

* * * * *

This series intentionally has not focused solely on Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, J.P. Richardson, or even Roger Peterson. Their stories are important but so are the stories of what the other members of the tour experienced. Buddy’s, Ritchie’s, J.P.’s, and Roger’s stories will be told at a future time.