Muscle Shoals is a small town on the Tennessee River near the larger city of Florence where, for some reason no one’s quite sure of during the mid-’60s, a lot of great musicians came together to make some of the greatest records of all time.

Currently touring the country is a documentary about the town, the studio and the musicians. Muscle Shoals is the first movie by director Greg ‘Freddy’ Camalier. It is a movie that anyone interested in R&B and soul music, not to mention rock & roll, will want to see.

The film is built around the story of Rick Hall, the man who founded FAME Studios. FAME is an acronym for Florence Alabama Music Enterprises. Hall’s life story is dark, full of truly horrible tragedies and brutal poverty, so the film is also the story of one man’s perseverance.

Fame was started in the late ’50s in Florence, Alabama, by Hall, Billy Sherrill and Tom Stafford — who soon moved on. Sherrill became a major Nashville record producer and was basically responsible for the career of Tammy Wynette. Hall then moved the studio to a former tobacco warehouse in Muscle Shoals and, in 1961, had his first hit with Arthur Alexander’s “You Better Move On,” which a few years later was recorded by the Rolling Stones. Interestingly enough, several of the musicians on that record, bassist Norbert Putnam, pianist David Briggs and drummer Jerry Carrigan, would also move to Nashville and become well known studio musicians and eventually producers. Hall used the money from the record, which reached #24 on the Billboard chart, to build another studio, and had another hit, “Steal Away” by Jimmy Hughes on FAME Records. Word of the studio began to spread and soon producers were bringing musicians to record there. One of the biggest hits was the Tams’ classic “What Kind Of Fool.” Soon, Joe Tex was recording there — though he used his own band. The next big album to help put Muscle Shoals on the musical map was Tell Mama by Etta James.

In 1966, Muscle Shoals broke in a big way with Percy Sledge’s “When A Man Loves A Woman.” The record was actually recorded at a smaller studio in Florence, Norala owned by a DJ aspiring to be a record producer, Quin Ivy, and included a couple of local musicians who had been working with Hall as well as the Memphis Horns. Ivy knew Rick Hall had connections to legendary producer Jerry Wexler, and asked for his help. The song shot to #1. Wexler, who had problems with Stax/Volt in Memphis, decided to use FAME Studios instead, and sent Wilson Pickett to record there. Wexler brought in some musicians from Memphis and elsewhere, but did use the house drummer, Roger Hawkins, and guitarist Jimmy Johnson, resulting in a number 1 hit: a cover of Cannibal! & the Headhunter’s “Land of 1,000 Dances” and quite a few other top ten hits. The next artist Wexler brought to Muscle Shoals made history: Aretha Franklin. Franklin recorded a few songs at Fame, most notably “I Never Loved A Man The Way I Love You,” but when her husband caused problems, Wexler moved the sessions to New York and brought the Muscle Shoals Rhythm section with them. Suddenly, these small town musicians barely making a living where in demand.

The film goes into all of this in detail and amazingly enough there is footage of both Pickett and Franklin, as well as interviews with Franklin.

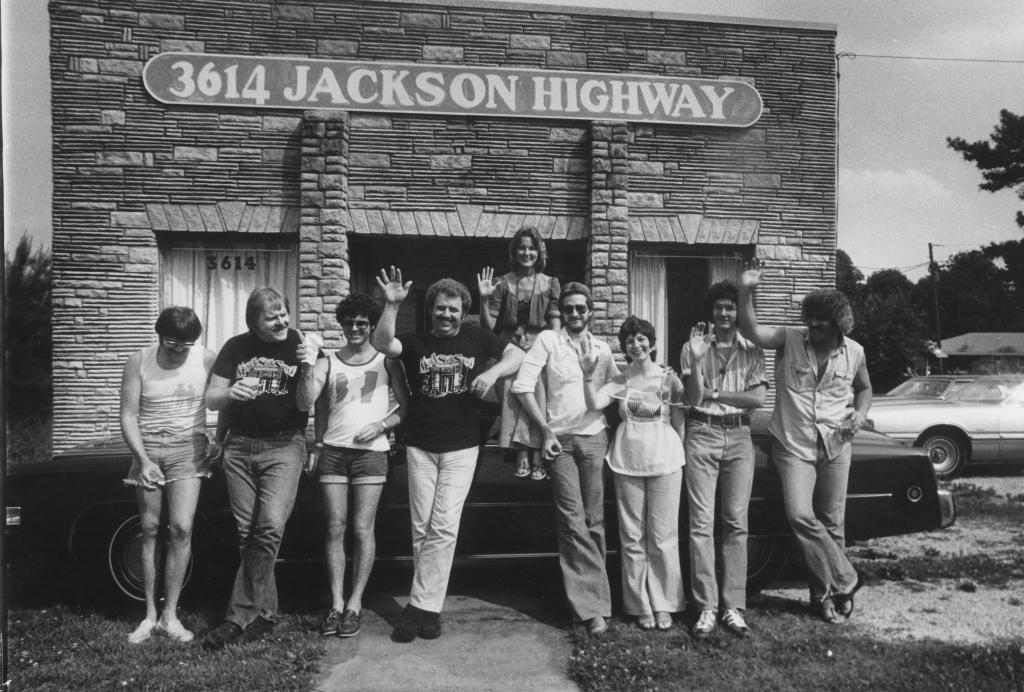

But a pair of years later in 1969, the rhythm section, Jimmy Johnson guitar; David Hood, bass; Barry Beckett, keyboards and Roger Hawkins, drums split from FAME and Rick Hood, and, prompted by Wexler, formed their own studio Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, and eventually became known as The Swampers, thanks to the famous line in Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama.” Over the next decade and into the ’80s, numerous musicians would record there, starting with Cher and Boz Skaggs, but also the Rolling Stones, Paul Simon, the Staple Singers, and Bob Dylan among many others.

Hall started recording country and pop acts, but with the split, the era of recording great R&B and Soul in Muscle Shoals was pretty much over.

The film primarily focuses on Hall’s story. In addition to interviews with the Muscle Shoals musicians, there are also interviews with others who were a part, such as the brilliant songwriter Dan Penn, Percy Sledge, Clarence Carter, and one-time Grateful Dead singer, Donna Jean-Godchaux, who it turns out was a backup singer at Muscle Shoals. In addition there are interviews with outside musicians who recorded there such as Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, Steve Winwood, Gregg Allman and Jimmy Cliff. And also for some reason, Bono is included in all of this. In fact, he’s one of the first people you see unfortunately commenting on a host of topics from racism to where he thinks the sound came from. Frankly, it is the biggest mistake of the movie. The issue of racism is better told by the musicians themselves. The story of Muscle Shoals is that the musicians, often to the surprise of the singers who came there to record, were all white. When they talk of how they couldn’t have lunch together with the singers they were working with, it makes the point much more vividly than anything Bono has to say.

Considering this is Camalier’s first film, he did a good job — but there are problems. As the film goes on and keeps going back to Hall and his story, the interest starts to wane. There are several shots of the Muscle Shoals landscape and surrounding area, but you don’t feel the poverty these musicians came from.

However, there are several great stories told about the sessions with Pickett and Franklin, about Duane Allman, who essentially got his start at Muscle Shoals, and of Lynyrd Skynyrd which are best heard and seen in the film with some incredible archival footage. When the various guys in the Swampers and the other session musicians talk, you wish the focus was more on them and a little less on Rick Hall. It is their stories and the archival footage that most of all make the film worth seeing.