This is the latest article in the popular Blues Law series by lawyer, author, and radio personality Brian Lukasavitz, “The Blues Attorney”, that explores interesting and landmark law cases related to the blues genre.

This is the latest article in the popular Blues Law series by lawyer, author, and radio personality Brian Lukasavitz, “The Blues Attorney”, that explores interesting and landmark law cases related to the blues genre.

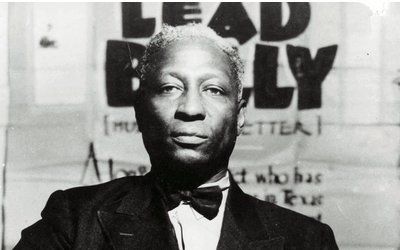

Over the decades, the story of friendship and collaboration between musicologist John Lomax and folk/blues singer-songwriter Lead Belly has reached mythical proportions: one can hardly discuss the career of one without including the other. Sadly, the relationship was more myth than fact — and the legal entanglement between the two negatively impacted both careers.

John Lomax began making “field recordings” of various folk music styles, primarily on work-farms and in penitentiaries throughout the South, starting in 1933. Private grants and the Library Congress funded Lomax’s travels and archiving of work-songs, reels, blues, ballads and folk songs. In July of 1933 at the Louisiana State Prison in Angola, Lomax, armed with his new, state-of-the-art phonogram, met and recorded Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter. In 1934, when Lead Belly was released from Angola, he persuaded Lomax to hire him as his assistant.

There’s a longstanding legend that Governor Oscar Allen pardoned Lead Belly after hearing him sing. The truth is that Lomax had delivered a recording of Lead Belly, however the folk singer was not pardoned at that time. The more mundane truth is that Ledbetter was eligible for early release based on good behavior. Later, Lead Belly would be pardoned by a different Governor, Pat Morris Neff, while serving time in Texas, thus adding credence to the earlier myth.

Many believe that Lomax and Lead Belly collaborated for the bulk of their careers. In truth, it was little more than five or six months. With Lead Belly assisting Lomax as driver and recording assistant, they spent the next few months finishing Lomax’s archiving project before heading to the lecture-circuit on the East Coast. In January of 1935, Lead Belly signed a management contract with Lomax. This contract stipulated to the split of performance fees, royalties, assignment of copyrights and responsibilities for both parties. The partnership with Lomax quickly soured. Frustrated by the working relationship and monthly payments, Lead Belly would eventually hire legal counsel to sue Lomax for payments, royalties and dissolution of the management contract.

It is unlikely that Lead Belly’s suit was ever filed. However, after several months of negotiation, a settlement was reached which included one full lump-sum payment and a split of potential royalties from Lomax’s book; Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly. During this time, Lomax also secured a recording contract for Lead Belly with the American Recording Company (ARC). Unfortunately, Lead Belly recorded over 40 songs for ARC but, due the early releases not selling well, the rest were not released. After managing his own career, Lead Belly would contact John Lomax in hopes of securing a new management deal.

Adding confusion to the relationship between Lomax and Lead Belly, in 1939, Lead Belly found himself in legal trouble again. This time it would be Alan Lomax, John’s son, who would come to Lead Belly’s aid. The younger Lomax, who had a far different philosophy on race-relations and folk music than his father, arranged Lead Belly’s bail, raised funds for legal fees and assisted with financial support for the Ledbetter family. Alan Lomax negotiated a deal with the Musicraft Label to make a series of recordings that would earn a posthumous Grammy Award. Alan Lomax would also secure a long-term recording contract with RCA-Victor, as well as promote Lead Belly through radio-interviews and live performances. Alan Lomax would also record almost the entire Lead Belly catalogue for the Library of Congress. He would go on to further document Lead Belly’s stories and songs, but in time, their collaboration would end — seemingly on good terms. Lead Belly eventually moved to Hollywood, secures a recording deal with Capitol Records and was the first of many U.S. folk and blues artists to tour Europe.

Sadly, Leadbetter’s true fame and fortune eluded him during his lifetime. He died in 1949, six months prior to the release of The Weaver’s version of his “Goodnight Irene“, which was the beginning of an endless list of cover versions of his catalogue. He would eventually be nominated (and receive) multiple Grammy Awards for previous works, received an induction into the Blues Hall of Fame, and in 1988 was inducted into the the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In 2002, Leadbelly was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame for “Goodnight Irene”. John Lomax, bitter from the failed relationship with the folk singer, never formally represented any artists after Lead Belly.