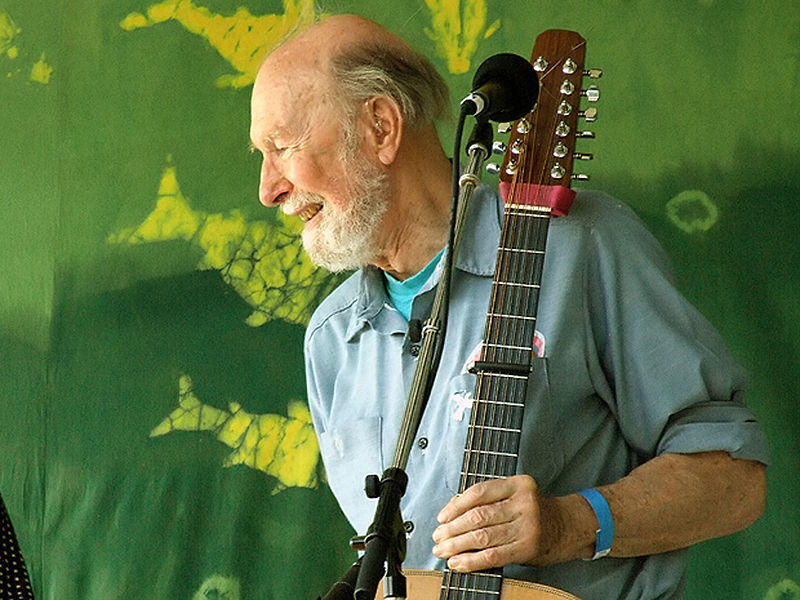

No one would ever say Pete Seeger was a blues singer, or even close. Occasionally, he’d dabble in some “close to blues” songs on his hundreds of albums, but it being Pete Seeger, they would always end up as another folksong. Yet Pete Seeger, in his own way, did a lot for the blues.

For starters, he hung out with Huddle “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, and learned how to play the 12-string guitar from the blues legend, and then wrote a book, How To Play The 12-String Guitar like Lead Belly. And there was an instruction record too. And of course, Seeger with The Weavers gave Lead Belly his first big hit with “Good Night Irene.” It was huge, and it was a song Lead Belly always knew it would be a hit. Had he been alive (he died six months before), he would’ve been thrilled. There’s a video of The Weavers singing the song on TV, and after the first verse, they stop singing, and Lee Hays talks about Leadbelly before they go on to finish the song.

Seeger and The Weavers would record other Lead Belly songs including “The Midnight Special” and “Rock Island Line,” and Seeger, ever the teacher, ever the person pointing the way back to the originators, would usually include Lead Belly songs in his shows for at least the next two decades. On his second Columbia album, The Bitter And The Sweet is a wonderful version of Lead Belly’s “Mr. Tom Hughes’s Town” (also known as “Fannin Street”) where his 12-string guitar work will surprise a lot of people.

Seeger also played quite a bit with Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and in 1957 recorded an album for Folkways, Pete Seeger And Sonny Terry at Carnegie Hall. Earlier, Terry (un-credited) played harp on Weavers records for Decca, such as Woody’s Guthrie’s song “Hard Ain’t It Hard,” where not only is the harmonica in Terry’s unmistakable style, but he ends his solo with one of his trademark “whoops.” In the mid-sixties, when Seeger, who was blacklisted from the three major networks, had a show on Educational Television, The Rainbow Quest, where his guest included, again, Terry and McGhee, but also Reverend Gary Davis and Mississippi John Hurt.

Seeger recorded over 100 albums in the ’50s for Folkways Records, and if you were to search their catalog (now at the Smithsonian Institution) you’d find he recorded two live albums with Willie Dixon (billed as Wee Willie Dixon) and Memphis Slim. He also recorded with Big Bill Broonzy and Sam Lightnin’ Hopkins. Not only that, in 1960, Seeger was the first person to present Lightnin’ Hopkins in concert as a special guest at a few of his concerts that year. It was Hopkins’ first time playing out of Texas, and I was lucky enough to see it when I was nine at my very first Pete Seeger concert at Town Hall in Philly. They sang some songs together and Hopkins did a couple alone. Since it was my first time, I have no idea what the songs were, but probably, one of the ones they did together was “Oh Mary, Don’t You Weep,” which is on a Folkways album. Hopkins was wearing shades and had a towel around his neck as they performed. It was the only time I got to see him, and it was my first time seeing a blues singer.

Seeger helped out the blues in other ways. He was one of the founders of the Newport Folk Festival, and the list of blues singers who played Newport is nothing short of incredible, Son House, Sleepy John Estes, Mississippi John Hurt, Skip James, Howlin’ Wolf, and many, many more. And because these artists played at Newport, that opened the door to them playing at other festivals, at colleges and in places they wouldn’t otherwise have played. Pete Seeger of course wasn’t the only one responsible, but he had a big hand in opening the door for these musicians and for all musicians who played roots music, whether old time country or Irish ballads.

So if you ever hear someone saying, “Oh Pete Seeger, he was just a folkie,” remind them that he hung with Leadbelly, jammed with Willie Dixon and Memphis Slim, and was the first to present Lightnin’ Hopkins in New York and Philly.