Bob Sarles is a San Francisco-based filmmaker who specializes in music documentaries. Readers have probably seen Bob Sarles films without realizing it. If you’ve watched the Rock and Roll of Hall of Fame induction ceremonies, many of the introductory films and especially the ones on blues, R&B and soul artists were done by Sarles. Several other of his films are used at exhibits at the Hall, as well as at the Stax Volt Museum in Memphis, and the Experience Music Project Museum in Seattle.

Bob Sarles is a San Francisco-based filmmaker who specializes in music documentaries. Readers have probably seen Bob Sarles films without realizing it. If you’ve watched the Rock and Roll of Hall of Fame induction ceremonies, many of the introductory films and especially the ones on blues, R&B and soul artists were done by Sarles. Several other of his films are used at exhibits at the Hall, as well as at the Stax Volt Museum in Memphis, and the Experience Music Project Museum in Seattle.

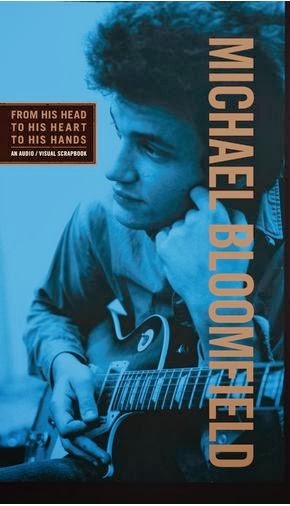

Sarles gives an in-depth look at what went into making Sweet Blues: A Film About Michael Bloomfield, and touches on other topics related to music documentary films as well.

Bob Sarles: I was a fan of Bloomfield since my high school days, which would have been a little bit past Michael’s time. I would probably say in the late ’60s, early ’70s I got turned on to Super Sessions, which probably would have been a year or two after it was originally released. And it was probably in my brother’s room or the older brother of a friend of mine – same process – and I just played that record until the grooves wore out. I was just really moved by Michael’s playing on that record. And so then I started digging a little bit, which coincided with my interest in becoming sort of a record hound and buying a lot of records and paying attention to the liner notes. And I realized that Michael was the lead guitarist on the Butterfield Blues Band album, or the first two albums that I really liked. And then I realized that he was the guy that was on Highway 61. And so I realized that I knew this guy’s playing, but I didn’t know it. And I started to get to know a little bit more about the guy’s body of work. I started collecting his records.

I moved to San Francisco in 1980, and I would see that Michael would be playing around occasionally. And the one time that I planned to go see him play, he was a no show. Michael was sort of notorious in those days for not showing up at gigs. So I never saw him perform live. He died then in the spring of 1981. And I just sort of missed my opportunity to see him live.

After that, I was starting my career as a film editor, and had an interest in – wouldn’t it be great if somebody would make a documentary about Michael Bloomfield? I realized nobody was. Why don’t I just try doing it myself? It took me a few years to get any traction. It wasn’t until the late ’80s that I started actually committing to getting a crew together and start interviewing people. I think it was after Paul Butterfield died in ’86, I was like “oh jeez, you know these people are mortal, you know? If I’m gonna do this, I better start.” So I started and my interviews were with B.B. King and Al Kooper and Bill Graham. And I just started stockpiling interviews when I had the opportunity.

I never raised any money to make the film. I started making the film before I actually had a career as a music documentarian. And that was something that sort of happened to me in the ’90s. So this project preceded my actual career that I’ve had making and producing music related film content. But I sort of just went at it and there were obstacles. At times there were legal obstacles, at times there were a misunderstanding with Michael’s estate that caused me to not work on it for a few years, and then I got permission to continue working on it.

And it was all stop and start and dribs and drabs in between. You know life and getting married and having a child, and getting divorced and continuing my career and getting remarried, and my life continued and I had a career that just blossomed making music documentaries.

But this always remained an unfinished project because of the economics of it. In order to finish the film, I would have to raise between $200,000 and $300,000 to pay for all the licensing and all the music publishing and the sync rights, and the archival footage and the photographs and paying people’s permissions and things like that. It gets very expensive, even for a modest project like this.

And so the film sort of remained like an albatross around my neck; not finished because I was busy making a living, and I am not independently wealthy and didn’t have the resources just to not work for six months and make this film.

So what wound up happening was just a year ago, in December of last year, I got a call from Al Kooper, who I’d become well acquainted with over the years that I was making this film. We remained in touch and had a friendly relationship and had discussed possibly doing something with this project in regards to a box set that he had hoped to put together for Michael’s record company. And this was a project that we had talked about for many years. It also had never come to fruition. But he called me last December and said that Sony indeed was willing to put up some money, a budget to put together a box set, and what he would like to do is have three CDs of music that he will compile, and he wanted me to take on the responsibility of producing the DVD that would be appropriate for the box set. And I jumped at the chance. I’m like, terrific.

And I talked to Sony, and they didn’t have a tremendous amount of money. They certainly didn’t have the money for me to finish the film that I had envisioned with all the stock footage and the time to tell the story that I would like to. But there was enough money to do I think a really fair treatment and to do an hour long documentary that presents some rare footage that people haven’t seen before, and really tells the story well and makes the case for why Michael should be remembered, why he was one of the greatest guitarists that ever lived, and why even though he’s sort of a forgotten footnote in the history of music, that he remains a linchpin, and somebody that should be remembered because he made such a huge impact on the music scene, and it reverberates today. And so I’m really grateful to Kooper for making this happen, and in the end I’m really proud with what we were able to do with the resources we had to make this film.

One of the things that I took away from the film, and I think it’s important is that he wasn’t into the rock and roll star trip. He seemed to run away from that really fast. To me at the time, he was the dominant guitar player from ’65 ’till the end of the ’60s. But he rejected all that.

One question I’m asked a lot is, why is that people don’t know who Michael is today considering how important he was then, and what I usually say is because he didn’t die in his prime. He walked away from it. He was long past the prime of his career when he did die. So he was forgotten. If he had died at age 27 like everybody else, he might be remembered like Jimi Hendrix. But he didn’t. He outlived his brief fame, and he walked, he just totally rejected it and walked away from it. Now on one hand, he had the financial resources to do that, ’cause he had a trust fund that gave him a small stipend to live on. So his rent was gonna be paid whether he worked or not. But more to the point is I just don’t think he had any patience for the bullshit of the music industry and the only thing he really cared about was the music itself, and his relationship with the people he admired. And I think that’s what motivated him, and I think everything else was just bullshit. And he had no patience for the road, and the shitty motels. And he got real tired of the partying on the road and all the chicks. Although he enjoyed it, it destroyed his marriage and he wasn’t very happy about that. And he talked in the interview I used in the film, that he’s out there busting his ass so that some record company rack jobber can pay for his kid’s bar mitzvah, that’s being done on his back. And he also didn’t like to be the product. He didn’t like to be the whole idea of the rock star and the idolatry and the focus on him. He could idolize B.B. King, but he couldn’t accept somebody idolizing him. And he just had no patience for it and he just completely retreated from it.

One thing that I didn’t get into in the film, that I would have if I had more space time is in the ’70s, he was doing soundtrack to Mitchell brothers porno movies. And somebody asked me once, wow his career had really degraded that much? I’m like, no, no, no, no, he dug it. He liked it! It appealed to his sensibilities. He thought it was a kick that he was doing like, there were like nurse nazis, and porno movies and Mitchell brothers, he just thought it was hysterical. He did what he wanted to do towards the end.

But in the end it was a sad story because he had problems that, had he been alive today, they probably could have been kept under control with the right meds. You know meds for bipolar disorder and things like that, and depression, that didn’t exist when he needed them. And so he self medicated with heroin. And heroin can kill you, and he died from his misadventures and it’s very tragic.

But with Michael, it’s all tied up with his genius and his brilliance. I think he was one of these artists, like a lot of artists, like Van Gogh, who part of their artistry is all tied up in their mania. You know I won’t call it insanity with Michael because I think he was an incredibly sane person. But I do think he was bipolar, I do think he was up and down. And I think when he was up there were flashes of brilliance. And he also couldn’t sleep for weeks at a time. And I think that had a very debilitating effect on Michael and ultimately led to his demise.

I’ve done a lot of different kinds of projects. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has been a client of mine for a couple of decades. We used to do a lot of the tribute films for the induction ceremonies. And so I’ve done a lot of blues artists, Buddy Guy, Dr. John, I guess you can call him a blues artists. But we’ve done maybe 20, 25 films for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremonies. We’ve also done a lot of films that are the exhibit installation films at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and we’ve made a lot of films that are in the Stax Museum in Memphis and the EMP Museum in Seattle, and we’ve done a lot of documentary work. We did a DVD about John Lee Hooker, one about Jefferson Airplane. And this is a passion of ours, my wife and I, who’s my partner in our little production company. And we try to do as much work as we can. We really enjoy it ’cause I feel like it’s a real privilege to, part of my job is to help tell these stories for posterity. And I don’t take the responsibility lightly. It’s an important thing.

One of the side projects we’re doing right now for the Rock Hall, they have an ongoing oral history project kind of like the Shoah Project — only for rock and roll. And when they came to me, and said, “we’re going to start doing this, what do you think about working on this thing”, I said it’s great. But you’re about 25 years too late. You lost so many people over the last couple of decades. But at least we got it started. We’ve done about 20 of these interviews so far and Jann Wenner personally chooses who does the interviews. And we’ve set up these interviews, and we’ve done Eric Burdon, Randy Newman, and a lot of Motown people, Mary Wilson. And it’s just a terrific privilege. We get to sit down for a day of shooting and get these people’s stories down for posterity.

I feel like I have finished an important version of the film. And if I should never get the opportunity to finish anything further, I’m really proud of this version of the film. Whether I can finish the film I originally intended to make really has to do with whether I can find an angel with deep pockets who will step up and cut me a check. It just seems like too much money to raise through a Kickstarter. I think Kickstarter is realistic if you’re trying to raise like, thirty or $40,000. But to try to raise four million dollars through personal donations, it just seems to me, that seems like a tough one. So I’m gonna sit back and see how this box set does first, and see if there’s an interest. It will be very telling to see how well this box set does as to whether I’ll be able to finish the feature length version of the film that I would like to.

There’s a fair amount [of Bloomfield footage in the film] , there isn’t a ton. If I had the budget, you certainly would get the feeling that there is a lot more footage. So with the modest budget, what I decided to do is purchase two complete songs, because usually what you do in a documentary is you license a lot of clips and you might play a piece of the song for 20, 30, maybe 40 seconds to represent that song, but then you have to move forward with the narrative. I’m editing a documentary of Wilson Pickett right now, and if I can play the song out for 30 seconds, that’s pretty generous.

So what I decided to do, I was gonna have a lot of footage that I could afford to license. I did most of the footage with photographs. But I wanted to show the songs in their entirety. So there are two songs that you see from beginning to end. And they play out in their entirety and that’s sort of not that common in a documentary like this. And I think that where I place those performances was sort of critical in the arc of the story, and the second performance which is Michael well past his prime playing the song acoustically on slide guitar is very poignant and sort of on the head with what’s happening in the narrative of the story. I kind of felt like that was a good solution to the issue of how are going to balance the budget with the narrative theme of the story.