(KANSAS CITY, MO) – Casey Bill Weldon, an influential blues guitarist, singer and composer of the 1930s whose whereabouts remained a mystery for decades, lies in an unmarked grave in Kansas City’s Lincoln Cemetery, not far from the headstone of another Kansas City musical pioneer, Charlie Parker. The Killer Blues Headstone Project, an organization that has placed markers on the graves of two dozen blues legends, has launched a fundraising campaign for a Weldon headstone in partnership with Kansas City-based blues historian Jim O’Neal, whose article in the January 2014 issue of Living Blues finally shed light on Weldon’s confusing biography. Folk Alliance International, which is holding its annual conference in Kansas City Feb. 18-23, has already announced it will be contributing to the fund. Individual donations may be made at killerblues.net.

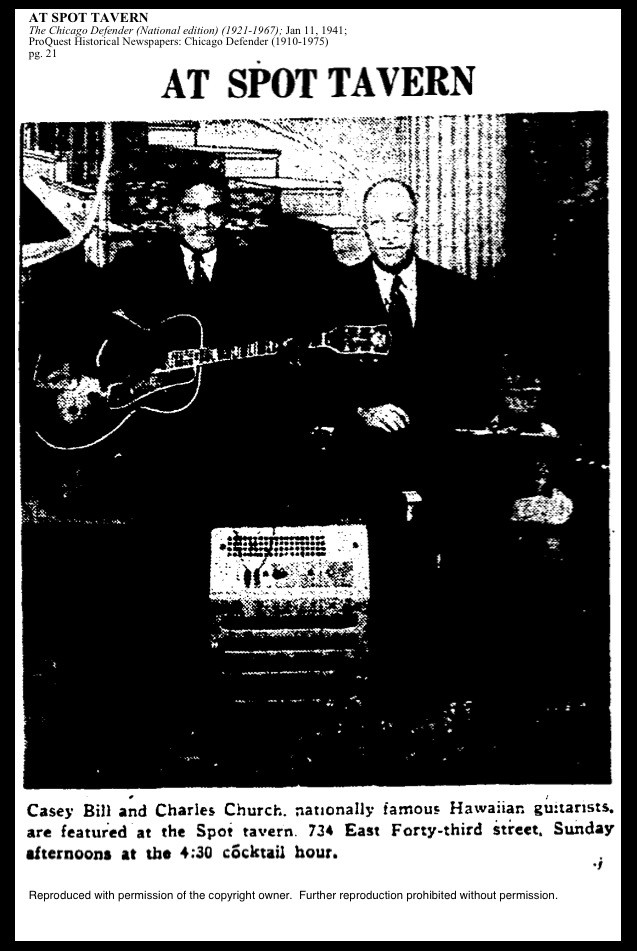

Weldon, billed as the “Hawaiian Guitar Wizard”, was a pioneer of electric blues and a songwriter whose works, especially the song usually known as “I’m Gonna Move to the Outskirts of Town,” have been recorded by hundreds of artists, ranging from Count Basie, James Brown and B.B. King to Willie Nelson, the Allman Brothers and Mel Torme. But after his brief recording career ended in Chicago in 1938, his path became challenging to trace. Second-hand reports placed him in California and Detroit, but he maintained ties with family in Kansas City, and it was there that he died on Sept. 28, 1972, at the age of 71. Various documents reveal that he had two legal names, William Weldon and Nathan Hammond, and may have used other names as well, while citing various birthplaces, including Plumerville, Arkansas, and Chanute, Kansas. His nickname “Casey Bill” was derived from a reference to K.C. as Casey that was in use in the ’30s. Weldon played a Hawaiian steel guitar, unusual in the blues, and scholars suggest his playing may have influenced the steel guitar tradition in Western swing and country & western. On his final recording session in 1938, he became one of the first blues artists to record with an electric amplifier.

Relatives of Weldon contacted by O’Neal knew him only as Nathan Hammond and were unaware that he was a noted musician who had written and recorded classic blues songs that could have been generating royalties for his heirs. O’Neal, who had been seeking information on Weldon since he co-founded Living Blues magazine in 1970, identified the gravesite in 2013 after his research led him to a one-paragraph obituary in Kansas City’s African American newspaper, The Call, the only notice of Weldon’s death published until the Living Blues article appeared.