This is the latest installment of our weekly series, The Language of the Blues, in which author and rock musician Debra Devi explores the meaning of a word or phrase found in the blues.

Grab a signed copy of Devi’s award-winning blues glossary The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to ZuZu (Foreword by Dr. John) at Bluescentric.com.

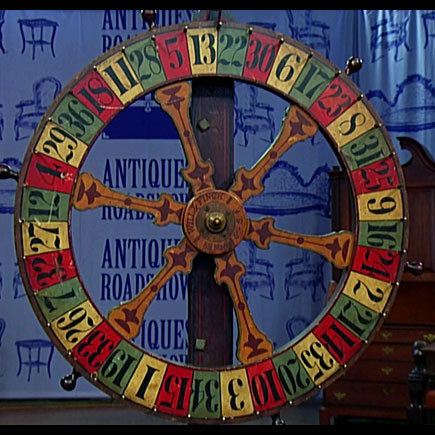

Policy game was an illegal daily lottery introduced in Chicago in 1885, supposedly by a bookie nicknamed Policy Sam. Players bet that certain numbers would be picked from a wheel that was spun each evening, which is why policy was also called “playing the numbers.”

The name “policy” came from the coded question bookies or “numbers runners” asked when collecting bets: “Would you like to take out an insurance policy?”

By 1901, illegal gambling had spread throughout the United States and laws were on the books prohibiting it. The games flourished, nonetheless, until states decided it was smarter to join ’em if you can’t beat ’em, and set up legal daily number lotteries of their own. The first state lottery was established in New Hampshire in 1964.

Policy was a cheap gamble. Shops took bets as low as one cent and people from all walks of life would regularly select a three-digit number, or gig, and place a bet with a their bookie.

Since just spinning a wheel left the bookies open to charges of fraud, the winning numbers came to be selected in a wide variety of fashions. In New York during the 1920s, bets were made on the last three numbers of the daily Federal Reserve Clearing House Report. In the South a policy game called The Cotton Exchange derived its winning numbers from the daily spot prices for cotton on the Chicago Board of Trade. In Florida in the 1940s, a game paid off on the last two numbers of the daily Cuban lottery. The payoff in 1948 for that game was $65 for a $1 bet. Regardless of how the winning number was selected, the next day winners could collect from their bookies.

Gamblers searched their dreams for signs they looked up in “dream books” like Aunt Sally’s Policy Players Dream Book to try to predict winning numbers. Dream books would link dream images, such as a dream of a train, to numbers. The dream images were listed in alphabetical order, with numbers beside each item. A cat represented the number 14, for example.

Dream books and policy gaming appear in many blues songs written from the 1920s to the 1950s. Blues songwriters used the numbers from the dream books as code in some of their lyrics. A player could decode the song by using a dream book. Blind (Arthur) Blake sang in “Policy Blues”:

Dream books and policy gaming appear in many blues songs written from the 1920s to the 1950s. Blues songwriters used the numbers from the dream books as code in some of their lyrics. A player could decode the song by using a dream book. Blind (Arthur) Blake sang in “Policy Blues”:

I begged my baby to let me in her door

Wanted to put my 25, 50, 75 in her 7, 17, 24

Blues and hoodoo expert Catherine Yronwode explains on her fantastic Lucky Mojo site that 25, 50, and 75 are all numbers that represent phallic imagery in the dreambooks- a vine, a cucumber, and an elephant trunk, respectively- while 7, 17, and 24 relate to feminine images, along with “digging” or “churning.” “The implications seem clearly ‘dirty,’” Yronwode wrote in her article, “Aunt Sally’s Policy Players Dream Book”; however, “Blake gets the last laugh on the listener, because an entirely different set of ascriptions shows that these numbers are demonstrably ‘clean’: The male numerals 25 and 50 can also be interpreted as ‘underclothes’ (25), ‘washing,’ ‘scrubbing,’ and ‘washboard’ (all 50), while the female numbers 17 and 24 can also refer to a ‘river’ (17) and ‘a washtub’ (24)–and so Blake might just as well be saying that he would like to put his wash-board in her tub of river-water and scrub his underwear clean.”

Pick up a signed copy of The Language of the Blues today!

Songs

“I Ain’t Got You”- Jimmy Reed

“Policy Blues”- Blind Blake (Arthur Blake)

“Hand Reader”- Washboard Sam (Robert Brown)

Video

“I Got My Mojo Working”- Muddy Waters (McKinley Morganfield)

VIDEO

Video

“Policy Blues” – Blind Blake