Gayle Dean Wardlow is universally recognized as one of the foremost authorities on the history of Delta and Country blues music and authored the 1998 book Chasin’ That Devil Music: Searching for the Blues, which was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2006. He has published articles, he lectures, and he has cobbled together one of the largest and most valuable collections of pre-war blues anywhere in the world.

During the Paramount Music Festival, he will be lecturing beginning at 10:30 in Port Washington on Saturday, September 2nd at the Country Inn. We spoke with Wardlow about some of the artists that recorded on the Paramount label, common practices of the record “industry” in the ’20s and ’30s, and why the Paramount legacy needs to be celebrated and preserved.

Barry Kerzner for ABS:

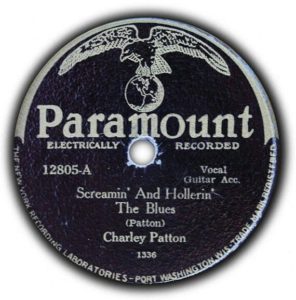

When you start talking about Charley Patton, there’s so much out there, maybe more myth than fact. Then too, there are two accepted ways to spell his name. What about Charley Patton and his relationship with Paramount Records?

Gayle Dean Wardlow:

Charley’s relationship goes back to a Jackson talent scout, H.C. Speir. Speir had a music store in the black section of Jackson [Mississippi]. He had been finding musicians, white, hillbilly, fiddle bands, blues singers, and he would send them to different labels. By 1929, he got a working relationship with Paramount where they would take anyone he’d send to Milwaukee.

Turns out that he heard about Charley Patton from Bo Carter. So, he went up to Dockery Plantation and auditioned Charley Patton. We don’t know if he’s born in 1887 or 1891. Some of that comes from his WWI draft registrations – is how old he thought he was. He lists it as 1887. Speir auditioned him and said, ‘I realized he had five or six different songs, and I knew he would go.’

In those days, companies always wanted someone who had at least four original songs. Charley had a lot more than four original songs, so Speir arranged for him to come to Jackson, and pay his expenses when he got there. They put him on a train and sent him to Richmond, Indiana for a month, month and a half. Paramount was building a studio in Grafton, so they came out of Chicago and Marsh Studios, so they rented Gennett Studios in Richmond, Indiana. That’s where Charley made his first songs. Probably around 12 or 13 songs were recorded at his first session, June 1929.

Immediately, his first record, ‘Pony Blues,’ became a big seller. Patton’s records just sold in Mississippi extremely well.

And then?

They got him back in the studio by December [1929]. He recorded again, for Paramount, and he had a fiddler with him named Henry Son Sims. Well, Son Simms is the guy who had the string band that Muddy Waters first started singing with, that Allan Lomax would record in 1941, ’42.

That was on Stovall Plantation.

So Patton became a very good seller, and Paramount began to push him as a top artist because Blind Lemon had died that December of ’29 in a snowstorm there in Chicago.

Patton – I call him the originator of Delta blues. He’s playing by 1909. The guitar started coming into the Mississippi Delta in the early 1900s. The Mexicans brought the guitar to the delta. That’s how they learned what they called ‘Spanish Tuning,’ open G tuning. Also, you could buy a guitar from the Sears Roebuck [catalog]. There were no music stores in the delta. There were only three towns of any size: Greenwood, Clarksdale, and Greenville. They were all anywhere from five to twenty thousand people.

Before the guitar came in, it was banjo, no?

No, not really. In the mountains, black musicians played open back five string banjo, but in Mississippi, in the delta, before the guitar, the only little instrument that would have been available would have been the harmonica.

Ah…

You have a harmonica because they’d been around since civil war days and probably, you had the fiddle. You had black fiddlers, like Son Sims. He learned from his father, who was a slave. Before the guitar gets into the delta, there just wasn’t a lot of music being played. Somebody could have a washboard, or a harmonica or a jug, but the guitar really made the difference.

Why are there two spellings for Charley Patton?

I’ll tell ya why, because he spelled it on his draft registration as l-i-e, Charlie, l-i-e. But Paramount, of course, just writing down the name, he said ‘Charley Patton’ when he recorded, and the people Richmond Indiana just wrote down C-h-a-r-l-e-y. The Paramount records all came out as l-e-y.

He seemed to prefer l-i-e.

So, once they checked the draft registration, he gave his year as like, 1885, or 1887 as being born. He probably did not even know when he was born.

That was fairly common back then though, wasn’t it?

In those days, the only way your date of birth was recorded was usually in a bible, by your family.

In the state of Mississippi, like most southern states, it was 1912 before they started keeping birth and death records. So, if you died before 1912, there was no record of your death except say, in the family bible, or family memoir; or the day of your birth.

Paramount recorded more than blues.

A lot of people think that they just recorded blues. Well, not just blues. Paramount recorded black preachers, black quartets, and quartets sold.

Those preaching and gospel records will keep you glued to the back of your chair.

They will. Something I learned from Mr. Speirs; whatever sold… Paramount would try something, and whatever sold they tried again. Paramount, for the first four years, lived off women blues singers and gospel quartets.

And after that?

Suddenly, late 1926, they find Blind Lemon Jefferson in Dallas and his first blues record comes out and bam! It sells and sells.

When they got Blind Lemon, Paramount realized they had happened on to something. Within a few months after that, they had Blind Blake, and he was sent up from Jacksonville by a record store dealer down there. Paramount couldn’t compete with a major label like Victor or Columbia as far as paying money and have the big stars, so they looked for the smaller talent, and they used these record store people to send them talent. So Blake was sent up by a record store dealer in Jacksonville to record behind a woman singer, and he did and made a single, and it became a hit, “West Coast Blues.” So suddenly, Paramount has a whole new field: Guitar blues.

The other companies always watched what was coming out, and they started looking for guitar blues singers to record.

Would you say that Big Bill Broonzy was the bridge between the pre-war and post-war generation of artists?

Oh yeah. He recorded for Paramount in 1928 or 1929. He did one record that did not sell. By the mid-’30s Big Bill starts becoming a big star. By the late 1930s, he’s one of the best sellers. He’s also bringing in the ‘City Sound.’ He started bringing in a bass and a piano behind it. Speir said in the mid-1920s they begin to record with other instruments, and the old guitar blues was not the best seller.

By WWII, he’s selling very well. He sells very well after WWII.

He was fortunate in that he enjoyed a longevity.

He first recorded in ’28, ’29, and he’s still recording in the early ’50s.

Let’s talk about these scouts like Mr. Speir for a moment. Paramount and other companies counted on them to send talent their way, or hip them that a talent was there.

They relied on them to send musicians they found in the south to Chicago. H. C. Speir. He had a music store in Jackson [Mississippi] from 1925 ’till around 1940 on Farish Street, and he had 90 percent, black customers.

Speir in Jackson, and Ashford in Dallas, and a guy named Harry Charles in Birmingham were Paramount’s three top selling scouts.

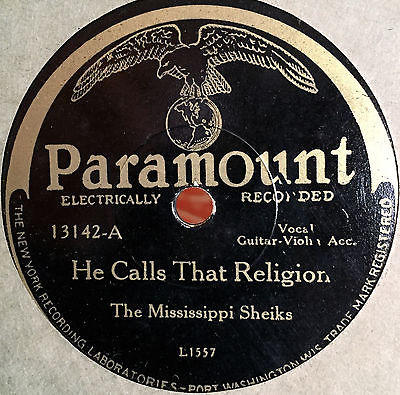

What about the Mississippi Sheiks?

The best Mississippi Sheiks records, believe it or not… They redid “Stop and Listen” and called it “New Stop and Listen” and they also did “New Sitting on Top of The World.” That is the last black group to record for Paramount, in early 1932.

1932 was the worst year for records and the companies almost all went out of business or just stopped issuing records hardly. They started back in 1934, and the Sheiks started back recording for Bluebird. You’ll find a recording on a reissue called “Pop Skull Blues,” It’s a remake of Tommy Johnson’s “Big Road Blues.” It’s perhaps the best Sheiks record of all.

The thing with the Sheiks was like Bo Carter made some recordings on his own, and …

Bo records first as Bo Chatmon. He does “Corrine, Corrina.” Well, he was under contract, and this Okeh label was gonna come in and record in Jackson Mississippi. Speir told me, ‘Well I wanted to record Bo, but he’s under contract, so I named him Bo Carter.’ So, Bo Carter got his name from Mr. Speir, the record store owner.

Interesting.

They recorded there, The Mississippi Sheiks and Bo Carter, and the same man who did the session for Okeh, was a man named Polk Brockman had worked out of Atlanta and mainly recorded hillbilly, but he did all the southern recordings as of 1928 by himself. He picked up Bo and the Mississippi Sheiks in 1934 and took them to Bluebird. Bo’s records kept selling, so he kept being recorded up until about 1939, and the Sheiks through about 1935.

What about Sam Chatmon?

Well, let me be kind. Sam always claimed that he was one of the original Mississippi Sheiks; it’s not true. The original Mississippi Sheiks were Walter Vinson and Lonnie Chatmon, the fiddler. The reason I know that is because I interviewed Walter Vinson in Jackson Mississippi one time when he was home from Chicago. He told me, ‘Me and Lonnie were the original Sheiks. They put some records out that says “Mississippi Sheiks with Bo Carter” on the Okeh label, ’cause Bo was there recording on his own, and he may have sung a duet with Vinson. After the Sheiks broke up, Sam and Lonnie recorded as the Chatmon Brothers.’ If you check around, you’ll see that 1936, 1937, the Chatmon Brothers recorded for Bluebird.

So later on when they found Sam, no-one else was alive, Bo was dead, so he said, ‘I was one of the original Mississippi Sheiks.’

Why was Marsh Studios was so important?

After WWI, records take off and start selling. The major companies were Victor, called Victor Talking Machines. Later on, RCA Radio bought the company and became RCA Victor. Victor and Columbia were the two biggest companies, and you had small companies in the 1920s also in in New York, where they had their main studios. Victor had studios in Camden, New Jersey, where they pressed the records.

In Chicago, there were one or two attempts at recording studios, and this guy Marsh puts in the best studio. He started out as acoustic. Paramount decided in 1922 to get into the record business and just do ‘Race Records’ as they called it. They had a little studio in New York City where they did some recording, but Marsh was in Chicago, and he had the best studios. Paramount decided to use Marsh Studios.

The quality, unfortunately, is very poor compared to other studios. He started out with acoustical, then electrical, and he had a big horn you sang into, and he put a mic in front of the big horn. Paramount used Marsh to make their masters probably up ’till 1929. The reason was that they were in Grafton in Port Washington, and in Chicago, they had Mayo Williams, the black talent scout or recording director, and he was doing all their recording in Chicago. Marsh Studios was closer, so it did a lot of their recordings. Marsh was it – there was no better studio in Chicago.

The other thing is Paramount didn’t have recording equipment. All the major recording companies starting in about 1925, would come down south and stop in Atlanta, and record for a week. They’d go to Memphis and record there for a week or ten days, then go to Dallas, and then come back to New Orleans. They recorded any type music; it wasn’t just blues. They recorded anything they thought would sell. The major companies did that up until 1932. The last Southern session was held in Dallas, February 1932, Victor; and that was it. There were no other sessions in the south until 1939.

Why is it so important to keep the Paramount legacy alive?

Because they recorded the very best of a lot of artists from jazz, especially into the Mississippi blues, guitar guys out of Mississippi. Charley Patton, Son House, Willie Brown, Tommy Johnson, Bracey. It keeps the legacy of Delta blues, which feeds into Chicago blues, post war. If Paramount had not existed, there would have been a tremendous amount of talent that would have never got recorded.