It took a while, but were able to have a chat with Mike Zito. Guitarist, singer, song-writer, and producer, Zito is one of the busiest artists on the circuit today. He has a brand new album, a very recent Blues Music Award, and tours almost non-stop. He’s also a genuinely humble and generous man.

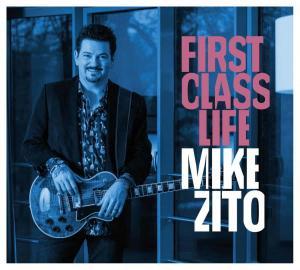

We spoke about the music on First Class Life, what being Rock Blues Artist of the year means to him, and what’s next for Mike Zito.

JD Nash for American Blues Scene:

So where are you today?

Mike Zito:

I’m off and we’re in Ohio. We’re driving to Columbus, all relaxed and drinking coffee. It’s all good.

At this time last week you were just finishing up a tour with the Blues Caravan. By Wednesday you were in Memphis, playing at the Rum Boogie. On Thursday you won Rock Blues Artist of the Year at the BMAs. Friday First Class Life dropped and you did an album release party in your hometown of St. Louis. Musically, have you ever had a more fulfilling week?

It’s been quite a week. No. I mean, I knew I was going to be working that hard. We recorded the album last November, but planned the release for when it happened. I knew I was doing the tour in April. We also knew we’d be back in time to go to the Blues Music Awards. Of course now you can put a record out any day of the week, where it used to be just on Tuesdays. Our idea was to put the album out the day after the BMAs, so that while we were there we could tell everybody about it. I never even thought about winning, but that sure made it better.

How did the release party in St. Louis go?

That probably meant more to me than ever before. I never had a feature article in the Post-Dispatch. My success has come in Texas and I don’t live in St. Louis anymore, although it’s still my home town. I got a nice article, did a nice interview on KDHX, and it worked out great that we were able to play on the day of the release in my home town. We had a great show. We played with Jeremiah Johnson, who I’ve known for 25 years. It was a really great show.

How is First Class Life going so far?

We’re getting great reviews. I keep reading, “this is your best record yet,” and that tells me that I made a record that people like. There’s no punches pulled, it’s just a blues record. It wasn’t on purpose, but eventually you get to that point. I wrote a bunch of songs and realized these are blues songs, we’re going to make a blues record apparently.

I know “Mississippi Nights” grabbed our attention right from the jump.

Good. That means you get the idea of what we’re doing. I’ve always wanted to play blues songs. At first you kind of mimic the songs, but then you get to the point where you want to make them your own. That’s what I’ve been trying to do. I’ve always had it in my head that if I keep doing it right, then maybe one day it’ll pay off.

You described this album as a rags-to-riches story from your own experience. One thing I’ve always noticed about you is that you make sure everyone else is taken care of as well. A good example is the fund raiser you did after the Houston flood.

I didn’t do that for credit or to promote myself. It was literally just the way the chain of events happened. We were coming back from Wisconsin and couldn’t get into the city. It took days, and rental cars in order to get home. Once the guys in the group got home, they couldn’t get back out, because the city was closed down. Thankfully our house was fine. Our block was fine. Nobody in my family was able to work, so my wife said, “if you can, you need to go to work.”

I literally, illegally, snuck out of town. I got to Louisiana and got on a plane. As I’m traveling, I’m looking at all my musician friends back home that were all out of work. They were filling sand bags, putting people up, helping feed people at local churches, but they didn’t have gigs. I’m lucky enough that I can work all over the world. I got out, and I went to work. I decided I should do something for them.

I just went to my first gig that night at Ace’s in Florida, put a tip jar out, and asked the crowd if they could fill it up for the musicians back home. I’ll be damned if they didn’t put a thousand bucks in that tip jar. That’s when it hit me that we could actually raise a little bit of money here. We ended up raising enough money that 25 musicians got $500 each. I just made sure the money got to good folks who really needed it.

That kind of moves into a couple songs on the new record. “The World We Live In,” and “Time For a Change.” There’s a lot of social consciousness in this album.

To me that’s really important. All the BS about you’re a liberal, or you’re a conservative and let’s call each other names, all of that takes the responsibility off of you. You just pick your side and wave the flag for your team, rather than sitting down and having a conversation with someone you don’t agree with. You’ll find you have more common ground than not. That irresponsibility, to me, is just lazy bullshit. People you don’t agree with are who you should be interacting with the most. It’s way easier to lay on your ass, looking at Facebook, than doing some service work to help other human beings. That’s the change I think it’s time for.

That’s on a national and even global scale, but you also brought it home, locally to you, on “Old Black Graveyard.”

Blind Willie Johnson is buried in Beaumont. THE Blind Willie Johnson. They had no idea where that guy was buried. I mean for 50 years they didn’t know where he was. He died of pneumonia in an old burned out church with no roof, and none of the hospitals would help him because he was black. The only reason we even know that story is because he was a famous musician. Most people aren’t famous, so you can imagine the thousands of stories of people who we may never know where they’re at. Not just blacks, but poor people in general.

It took ten years but they narrowed down his resting place to this plot of land in Beaumont. It happens to be in a really poor African-American neighborhood. The cemetery is on Barbara Lynn Way, named after the great blues singer. In a corner lot there a bunch of old headstones that are under the ground. They’ve been turned over and buried by hurricanes. Nobody takes care of them, they’re just old headstones in a neighborhood.

They eventually put up a memorial to Blind Willie, and we’d go visit the memorial. Then you’d see all these partial headstones sticking up back in the woods, and say hmm, I wonder who that is. It’s interesting, so I made up a little ghost story about it.

I think this is possibly your most feeling album to date. But it’s not all heavy either. Songs like “Back Problems,” and “Mama Don’t Like No Wah-Wah” bring out a humorous side.

Oh man, that’s a great story.

I love that when Bernard [Allison] takes that solo, he’s all over that pedal.

Yeah, all over the wah-wah. You know Koko Taylor didn’t know what any of those things were. She just called them wah-wahs. He [Bernard] didn’t even bring a wah-wah to the gigs when he played with her. He brought maybe a chorus effect or something he thought he could sneak on stage and she wouldn’t know. But, she caught him. “Turn that shit off. Mama don’t like no wah-wah.” It didn’t matter what it was, to her it was a wah-wah, “Turn it off.”

Now that First Class Life is out, have you begun any work on the next record?

Right now this is it. This is the record. I’m always thinking about what I’ll do next. In the back of my head I have two or three what I think are good ideas. It’ll be a while before anything else happens and I want to see where this one is going to take us.

Will it stay on the more contemporary blues track that you’re on now?

Yeah! I mean that’s always what I’ve wanted to do, and winning that award Thursday really set it off. Everybody’s been teasing me about getting a big head, but actually it’s very humbling. It gave me the confidence that I’m doing something right, but at the same time, I have a lot more to do. It’s not the time to lay back. It’s the time to step up and really do the work. I’m responsible now. I have to be worthy of this prestigious honor.

Anything else you want to let us know about?

Two things actually. I opened my own studio last year in the garage at my house. We actually recorded ‘First Class Life’ in that studio. It makes it simple that any time I’m home, I can go out back and get to work.

Secondly, this year marks twenty years since the release of my first album. The first one was called ‘Blue Room,’ and I recorded that when I was living in St. Louis. We played in front of Walter Trout that year. I made friends with him and loved that record. He sent it to Ruf Records, and they were going to sign me, twenty years ago. Then Walter found out I was a full-blown alcoholic and drug addict. After giving me a heap of shit, he told the label that I wasn’t ready.

Now twenty years later, Ruf and I have decided that they’re going to re-issue my first record in November. I’m really excited about that. So when you ask me what’s next, we’re going to remaster that at the studio, coming up in the next month. There’s also some bonus tracks that were recorded live twenty years ago that we’re going to add.

I’m as excited about that as anything. That was such a turning point for me. That’s when everything changed. I think that’s as cool as it gets, for me.

*Feature image Savas Mallotides courtesy of Devious Planet