There was something about

There was something about

that city, though

it didn’t let me feel guilty

that I had no feeling for the

things so many others

needed.

it let me alone.

– From Charles Bukowski’s “Young in New Orleans”

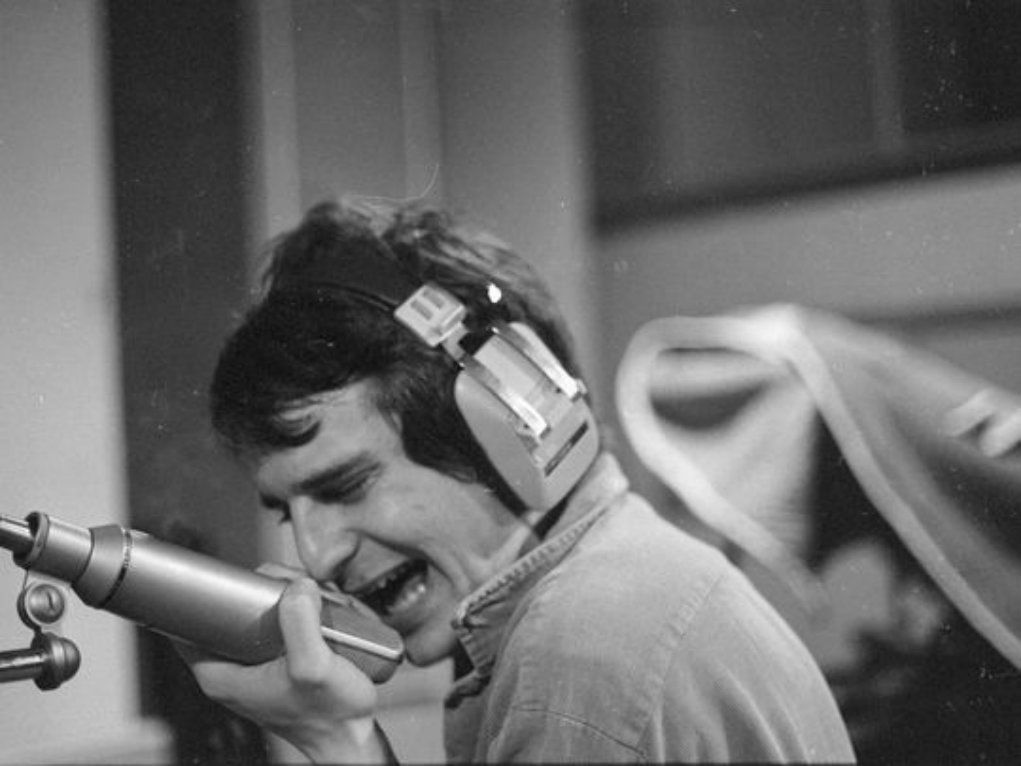

One could really get lost in New Orleans; lost in reverie, lost in the rhythm and blues, lost in the collective beat of the city. For Alex Chilton, this was especially true. You see, the commercial success of a #1 hit, The Box Tops’ “The Letter,” was something a teenager who sang with impossibly soulful grit only got to taste. And the power-pop perfection of subsequent Big Star never quite panned out the way it was supposed to. Outside of society, New Orleans was waiting for him.

Having long endured a cavalcade of disillusioned dreams, bad deals, and bad vices, Alex moved to the Big Easy in 1982 to make a new name for himself. But one that he didn’t necessarily want people to know. It seemed like as the cult following started growing in numbers and genuflecting before a Big Star catalog, Alex was eking out a living; his mythos sometimes at odds with his genius. And that kind of irony was not lost on him. Years later, when Big Star’s “In the Street” was adapted as That ‘70s Show theme song, he coined it “That $70 Show” for the exact dollar amount he got in royalties each time the show aired.

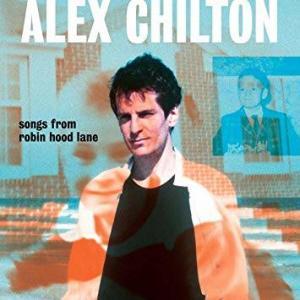

In case you missed it, February 8th saw the release of two new Alex Chilton compilations, From Memphis to New Orleans and Songs from Robin Hood Lane. The former is a compendium of his best work from rare ‘80s albums such as Feudalist Tarts, No Sex, and High Priest. The latter transports us back to post-war Memphis, where a 7-year-old Alex already had jazz coursing through his veins by way of a certain osmosis: his father Sidney’s expansive record library. His biggest singing influence was Chet Baker, and he engrossed himself in the Chet Baker Sings album. Songs From Robin Hood Lane features four previously unreleased performances in addition to recordings that have been out of print for some time now.

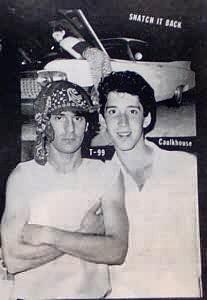

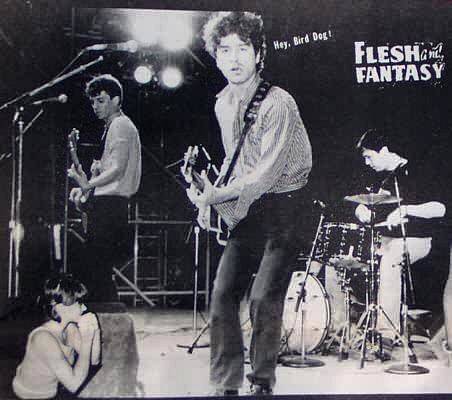

Playing on most of the material from this oft-forgotten period are bassist René Coman and drummer Doug Garrison, both of New Orleans’ own beloved Iguanas; the two were steady collaborators and toured Europe with Alex as a trio. René in particular summoned to resume Tav Falco’s Panther Burns, a blues/rockabilly outfit that Alex played guitar with and co-founded in 1979. A conversation I had with René about his late friend, a man of destruction and principles, proved to be every bit as life-affirming for me as I thought it would.

Lauren for American Blues Scene:

I’ve been listening to your Troubled Men podcast. Obviously the first one I listened to was the one in honor of Alex’s birthday with Doug Garrison and Johnny J. as guests. I learned more about Alex from you guys and your firsthand accounts of Alex’s eccentricity, wry wit, warmth, probity, tortured genius… He was just all of these things. And it seems he preferred or maybe even thrived in anonymity. Your thoughts on that?

René Coman:

… It feels a little bit dehumanizing, even though it’s not meant to feel that way — the adulation — but somehow it doesn’t really connect with you personally. It becomes a bit of a turn off. When you see people treating you like that, a lot of red flags go off and you think, “Oh, this is not going to be fun for me. This person is going to try to relate to something I’ve done that I don’t even relate to so much in the present.” He would get turned off by that. I talked in the podcast about the last time I saw him; I was mentioning how he was namechecked in Rolling Stone. And he’s getting a pained look on his face. I recognized that and I said, “Oh, you don’t like this.” He liked being able to play gigs and everything and enjoyed doing that.

From Memphis to New Orleans and Songs From Robin Hood Lane are two different assemblages of Alex Chilton recordings, both from a relatively obscure epoch of his career: the New Orleans years, where he would intermittently go back to Ardent Studios in Memphis to record. Am I accurate in my description?

I was a little distracted when people were referring to it as that. We recorded Feudalist Tarts there and then the No Sex stuff and High Priest. We did some recording in New Orleans. There was a mutual friend of ours that had a studio down here. I guess some of the stuff from the Cliches record is on the other disc. Some of the songs from Songs From Robin Hood Lane were done in New Orleans, but all the band stuff I did with him was at Ardent. We did some Panther Burns recording at Sam Phillips Recording Studio up there in Memphis, but then we also did Panther Burns stuff at Ardent.

You played with Alex starting with Tav Falco’s Panther Burns in 1982 and then a trio format, correct? How did you first encounter Alex?

It was the end of ‘82. I initially was just playing with Alex, but not playing any gigs. I was hired to play a gig that didn’t actually wind up happening. The rehearsal that we did for it was how Alex and I met. And then when Tav came down to New Orleans to try and get the Panther Burns going again, Alex said, “Well, get René.” Stanley Adkins, who had the offshoot band — Alex would sometimes play with Stanley. I guess I’d done some of those. It gets a little bit hazy back there. I guess the first Panther Burns gig I did was May of ‘83. Then that summer we went out opening a string of dates for The Clash.

I was going to ask you about that.

Yeah, that was a pretty wild time. The Panther Burns, of course, were always barely making it somewhere, riding on retreaded tires. The first day we showed up just barely in time to play the gig. So the next day they said, “Look, there will be a bonus for you if you show up on time.” I think we made that on-time arrival.

Didn’t you have a crazy tour manager that stole money?

That was when Doug and Alex and I were in Europe touring. That was a string of dates that, at the time, we played every country that was not behind the Iron Curtain in Europe. It was two and a half months, and we had already been on tour in the States for months. So, just a forever endless thing, and a lot of work and a lot of drives. I can’t say that he stole the money, but he certainly lost the money. It was a lot of really weird stuff that went down with this guy, and never really was resolved or explained. We started collecting money ourselves after that, and then the management company showed up and stranded us in the hotel lobby in Utrecht, Holland with all the gear. But that Clash run, there’s an incident that occurred in Knoxville, The University of Tennessee there that we were playing. It’s like 4,000 people or something — you’re opening for The Clash, and they have us in front of the front curtain. So, we’re lined up shoulder to shoulder. I call that execution style formation, where you can’t really play in a band like that. You can’t really hear anybody, because you’re so far away from the guy on the other end. So, you’re kind of setting yourself up for a hard time. So, we only have like three feet of stage before the end. We’re playing and something starts to go a little bit awry. It might have been a tuning issue or something, and we start to lose the crowd, which is easy to lose. You got all these people that want to see The Clash, and then the Panther Burns come out there and we’re playing this fractured rockabilly and psychedelic blues. The crowd started to turn, some people started booing. And then Ross Johnson, our drummer, starts tossing bite-sized candy bars into the crowd. Somehow this just inflames them even more. Somebody raised their arms up in victory, and then the whole place is just erupting in this massive wave of boos sweeping over us. I remember in that moment thinking, “Wow, this is really incredible to be so strongly hated by all these people.” And then we went into “Bourgeois Blues.” I remember getting offstage and saying, “Wow, that’s like everybody’s worst nightmare to experience as a performer, and we just went through it. And we’re fine. We’re alive, my family still loves me…”

Yeah, and it makes for a good story later.

Yeah, and it was really liberating. Because I thought, “Ok, that’s the worst that could happen? Well, that’s not too bad.”

It can only get better from here.

And I’ve always remembered that. I’ve always held that memory. It’s something I can tell myself: “Well, I don’t know what will happen on this gig, but one thing I know is that in two hours this will be over. And we will move on from there.”

How might you compare/contrast the two albums as it relates to rare, unreleased, or out-of-print recordings? I understand Songs From Robin Hood Lane hearkens back to Alex’s inceptive years when he was first heavily influenced by Chet Baker.

That was one of Alex’s favorite records. And when I first met him, he only had maybe 15, 20, 25 records at his house. But that was one of them. And I was into that kind of stuff already, the American Songbook, all that stuff. That was something we shared, and we would play all that stuff. And immediately when we went out as a trio, we included a lot of that stuff in our sets, which people would show up wanting to hear Big Star stuff or more Cramps-ish stuff. We would do some of that, but then we would pull out all these ballads and swing tunes. And he didn’t care if you liked it or not.

Do you anticipate that people will embrace it with an open mind and open arms? You know, those die-hard fans of Big Star’s jangly, hooky guitar arrangements?

Well, you know, there’s all kinds of different Alex fans. There’s Alex fans that come to him through the Cramps and love all that kind of stuff. And they’re like, “Big Star’s good, but…” It’s not their cup of tea necessarily. And then there are other people that love Like Flies on Sherbert, that super fractured, falling apart kind of thing.

I can’t think of anyone more iconoclastic in his influence. Because you know, you have someone who started in the Box Tops, then Big Star, then produced some Cramps albums, and then you have your protopunk songs like “Bangkok.”

Yeah, it’s true. And Alex did shift and had a lot of different things he could do and a lot of different things he was into. I think the Big Star stuff, in the revival stage — He enjoyed being able to go and play, but I get the feeling that, without putting words into his mouth, that it wasn’t something he really related to in the present tense so much.

I remember Tav Falco saying how Alex would create something beautiful and then want to destroy it.

A close mutual friend of ours said, years later after he passed, “Alex would spend all of his time when he met you figuring out what was cool about you and really be interested. And then once he had done that entire catalog, then he would start working on what was not cool about you.” When he was done with that, it might be the end. He might have amassed enough evidence to decide he didn’t really like you after all. So, maybe that carried over into some other areas as well. He would lose interest and move on to something new. But he always loved soul music and country music.

He just didn’t pigeonhole himself, like some of his fans did.

Right. And another interesting aspect of Alex’s confidence and lack of concern about anybody else’s opinion — I read one of those little slim books that come out on different bands. Somebody gave me the one on Alex or Big Star. A guy tells a story about — he was a musician and had brought Alex to play a gig with his band. I remember when this happened, but the guy tells a story about taking Alex to his favorite bar the night before to show him off, and he’s meeting some friends there. The guy comes out of the bathroom and Alex is sitting with his legs crossed, and he’s just swinging his head and rocking out to “The Logical Song” by Supertramp.

You know what, I love that song.

Yeah, well, a lot of people don’t. A lot of people would call it garbage. The guy comes up, and Alex is just really into it. And he’s horrified. He’s like, “What are you doing?” And Alex says, “This is a great song, man!”

It really is.

That’s how Alex was. He didn’t care if anyone else thought this was the least cool thing ever. If he thought it was cool, that’s all that mattered.

I can relate to that so much.

And that was a great quality of his: the courage of his convictions. It’s a really admirable thing.

Well, I think Chet Baker played trumpet on Elvis Costello’s “Shipbuilding.” So, that’s all the cool you need.

It’s pretty hard to outcool Chet Baker. I recently gave that same friend who made that comment — it was seven records originally, but it was on two CDs or something — all the Chet Baker stuff. The recordings are so small; there’s so little going on. It’s all just so sublime, because it’s completely unadorned. And you hear Chet so naked, and his sound is so small but beautiful. And his voice has the same quality to it.

I love his trumpet playing.

Yeah. You know, he’s a tragic figure. He embodies the whole decadent rock and roll, self-destructive aspect as well.

Well, I’ve listened to Songs From Robin Hood Lane, and these do sound like the standards sung by someone who really could incarnate the real deal ‘50s jazz. That might surprise someone who has only heard Box Tops or Big Star.

Alex did possess that quality. He just had a presence that could not be faked, that most people don’t have. You recognize it when you hear it, but it’s very difficult to generate as a contrivance.

Are there any songs on these albums that you hold dear to your heart for particular reasons?

Oh, there are some great ones. “Lost My Job,” “Underclass” … Those were fun to do. Alex gets a little political. “Thing For You” from High Priest… Yeah, I remember recording all these. It was fun to be in the studio. “Lost My Job” was written after we got fired from Papa Joe’s, which I talked about on the podcast. We were playing in a trio. Alex got this gig playing in a trio on Bourbon Street at this place called Papa Joe’s. He brought me in and said, “I got a bass player who’s better than the guy you have.” So, we started doing that. At some point, we made one comment too many to the drummer about the time. And he quit, but in actuality, we were getting fired. It was in the wake of that incident that we called Frank Riley. That was the birth of the trio going out on the road, which led to those New Rose Records that led to the Feudalist Tarts record. But that song was written before the record deal, which is kind of unusual. Because Alex didn’t necessarily write all of the time; he would write if he had a record to fill up. That’s one that he thought, “Well, maybe I should have some new material to go out here on the road.”

Is there anything you want to say about the release of these special collections? How are you feeling about it?

I’m glad that stuff came up in rotation, because I don’t think of it as lost. I’m glad it’s getting out there and that people will know about that part of his career if in fact it is an unknown. Some of the live recordings I hear of us from those days, I cringe a little bit because…

I remember you saying that on the podcast. Like, “That’s enough.”

Do you have to play the bass part and all the horn parts at the same time?

It was the ‘80s! Don’t be so hard on yourself.

Yeah. And really, Alex was digging it. If he would’ve told me to stop, I would have. There’s an applicable phrase that he uttered one time that I remembered and have used, which is, “So, you’re trying to wow them with the flashing fingers?” So, you think you’re going to impress somebody by playing some real fast shit? And of course, that’s not where it’s at. And people who try to do that are barking up the wrong tree. I loved the encapsulation of that idea. It’s so dismissive; it’s very Alex. He could be very biting and very funny. I was really nervous about doing the podcast. I thought it could blow up in my face easily. The only reason I went ahead and did it was, I thought, “Well, I’m going to control what comes out. So, if I don’t like it, I don’t even have to put it out.” But his wife texts me a week later, and she was really happy. She said she loved it and said, “The Alex that you describe is the Alex that I knew 97 percent of the time and one that I don’t see reflected in a lot of stories that I hear about him from the ‘70s and ‘80s that I don’t even recognize the person they’re talking about.”

People probably thought they knew him, but they didn’t.

Well, if you were one of the people who was on the outside and he was cutting or sarcastic to you…

Or the foolhardy, cocksure journalists that he didn’t care for.

Yeah. So, I think a lot of people had a brief experience with Alex that was not pleasant. So, they thought he was just difficult. That could be the case, I guess, but he could also be super sweet and really endearing. He was kind and a very sensitive guy. He had different sets of standards. Sometimes the standards would waiver. You know, it would be a little bit situational. But deep down he had some principles that he was trying to live by. He was trying to be true to himself. I know that when he came down here to New Orleans, part of that experience was him realigning with his principles. He felt like all the shit that had gone down in Memphis, it just got too ugly. Let me just go here and sequester myself and figure this out.

There’s people around who tell you that they know

The places where they send you, and it’s easy to go

They’ll zip you up and dress you down

Stand you in a row

But you know you don’t have to

You could just say no

– From Big Star’s “The Ballad of El Goodo”

That’s probably why he never wanted to talk about Big Star; it represented a part of his life he wanted to leave in the past.

I think there was a lot of disappointment. They’d done all this work and had all these high hopes.

They lost their distribution deal.

Right. The whole thing fell apart and the record didn’t come out. And the first two didn’t sell. It left a bitter taste in his mouth. I talked on the podcast about how he wouldn’t even play those records for us. He’d be like, “Here’s a song. Let me teach you a song.” Ok, can we listen to the record? “No, don’t do that. Don’t listen to the record.”

And Doug had to go out and get the record! I was going to ask you if there was anything you wanted people to know about Alex that they may not, but you definitely just covered that.

Yeah, and he was funny, smart, self-educated.

Autodidact, as you mentioned in the podcast.

He really was.

René Coman and Manny Chevrolet are the troubled men for troubled times. Their Troubled Men podcast has quickly become my new favorite. Grievances are aired, topics are erratic, guests are multifaceted, Manny digresses again… Troubled Men is a glistening example of how off-the-cuff repartee between two old friends can be funnier and more ingenious than any scripted network television show. You can do what I did and start with the Alex Chilton episode, and then go backward and forward from there.

Troubled Men Podcast

*Feature image Patricia Rainer