California is a melting pot of sound, and Dave Alvin was born a microcosm of exactly that. He and big brother Phil grew up in Downey, a suburb of Los Angeles, with a shared love of the blues. By the time they were teenagers in the ‘60s, they met Big Joe Turner at an L.A. club and quickly found themselves under his tutelage all the way up until his passing.

The brothers formed The Blasters in 1978. With Phil leading vocals and Dave writing the songs and bashing the guitar, The Blasters expertly — and loudly — blurred the lines between punk, blues, and rockabilly. And by 1981, following the exposure of a Queen tour, The Blasters released a major label debut album, hurling them into headline status.

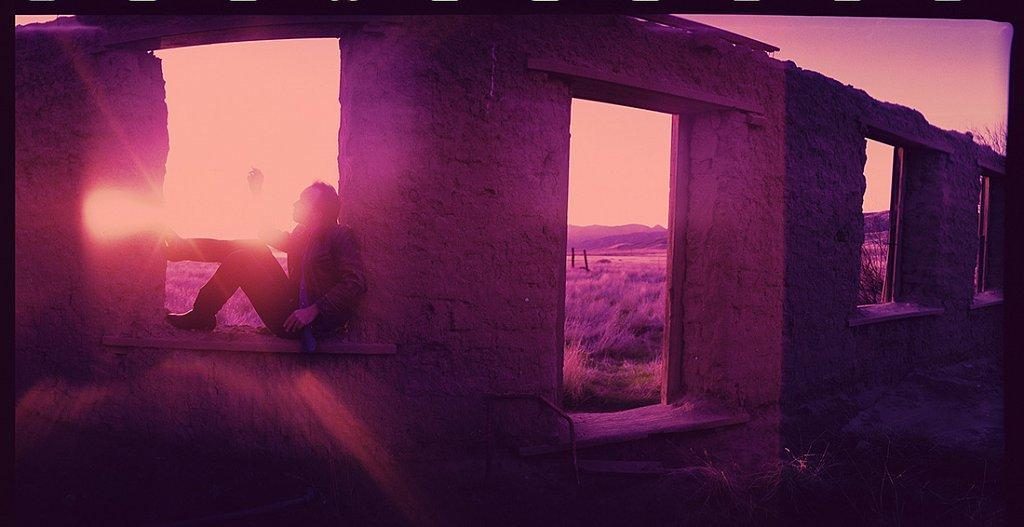

After stints in the Knitters and X, Dave was ready to go solo in 1987. He then went on to turn out the albums Romeo’s Escape, Blue Blvd, and Museum of Heart. 1994 saw the release of King of California, setting the gold standard for roots rock albums. With the encouragement of producer Greg Leisz, Dave finally found the huge sound he had been searching for all along — as heard in the album’s title track, in which visceral vocals and thundering instrumentals compete for your attention. On June 28th, Craft Recordings issued a special edition of King of California, and he is currently touring in support of the 25th anniversary reissue.

Dave, like King of California, has stood the test of time. He’s a Grammy winner, stirring singer, scrupulous interpreter, and gifted guitarist. But bred in his bones is songwriter first, and what makes him a paragon of songwriting is that he makes others aware of their musical heritage, whether they realize it or not. I imagine murky tintypes, or portraits of Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly weathered by time and the elements. And then I think of Dave Alvin as the panacea to reduce further fading of American roots music. In Dave we hear the sincere echoes of our folk forefathers.

American Blues Scene:

How does this collection of songs sound to you 25 years later?

Dave Alvin:

Pretty good, if I say so myself. There’s always something on whatever record where you go, “Oh, man. If I could do that again…” I’ve just gotten used to that. I remember the first Blasters record, hearing that and just wanting to go in and redo the whole thing. And now I’ve gotten to the point where it’s only a song or two where you go, “Ow!” You know?

Do you find dimensions of it that strike you just as emotionally, or maybe even more so now?

Probably more so, because there are certain people on the record that have passed away. And so when I hear them, I get choked up a little bit. There’s that aspect. I’m going to sound egotistical here, but overall I’m pretty proud of that record.

Oh, you should be.

It’s one of those records where, when we were making it — sometimes you just get a feeling like this is really special. Greg and I were making an album called Museum of Heart. And that’s when Greg started saying, “They’re recording your voice wrong.” What? What are you talking about? And he started using words like — because he and I had done tours, just the two of us, playing acoustically. On those tours he had heard something in my voice. Greg has worked with a lot of great singers, but he heard something in mine. He said, “I know how to get that. I know how to get what you’re trying to do.

The resonance.

Yeah. And also, he taught me — My big brother Phil in The Blasters was anti — you know what a capo is, right?

I do.

My brother for some reason hates capos. He called it — you were a chicken.

It didn’t feel natural to him?

Yeah, even though so many of our heroes — you know, I can point to pictures of everyone from Johnny “Guitar” Watson to Blind Willie McTell with capos on. It didn’t matter, though. Capos were stupid.

I’ve seen my favorite guitar teacher, Alan Stowell, play with one.

Oh, they’re great. I just bought into my brother’s crazy little theory. Most guitar players want to play in E, A, or G, right? So, you tend to write your songs in E, A, or G because you’re a guitar player. “I play really good in E!” You know? And Greg was like, “This song, your voice is best in B flat.” Well, I don’t want to play in B flat. Here’s a capo; use it. And that’s really what happened. Some of the songs are in really odd keys just because that’s where my voice landed, you know. It’s where my voice sounded the best.

So there are all these little things that Greg kind of opened my eyes to and expanded my musical horizons, which I’m forever in his debt for. And then the other thing that was sort of a mutual discussion was making the sound wide open. In The Blasters’ sound and the sound with my first couple solo records was dense, which is not bad. It’s a decision you make. Like in The Blasters, it was, “1, 2, 3, everybody go!” You know? A lot of the old records we grew up listening to were like that. But Greg and I really wanted King of California to sound — you know, there’s a…

It does. One song I can’t get enough of is the title track. To me, it embodies the quintessence of the classic country I grew up on — in that your voice and the bluegrass instrumentals really drive the melody. To me, it also has the vocal sensibility of a Gordon Lightfoot song.

Yeah. Certainly. Certainly.

Not sure if that’s quite what you were going for, but please take that as a compliment.

Well no, I take it as a big compliment. It’s not what we were going for in a sense that — we didn’t go into the studio and say, “Hey, let’s cut a Gordon Lightfoot song.” But you know, the idea was kind of a mixture of the first couple of Gordon Lightfoot records, really where he was just bass, drums, and acoustic guitar.

Yeah, where his voice drives everything.

Yeah. And then, sort of records by Fred Neil and Tom Rush and people like that.

Those instrumentals are just breathtaking to me. Such a beautiful song. I had it on repeat today actually.

Well yeah, Greg is — he was always becoming a well-known studio musician, but nothing like he is now. I make the joke: you don’t say what records he’s on; you say what records he’s not on. That’s a shorter list, you know? Ok, he’s not on ‘Sgt. Pepper’s,’ and he’s not on ‘Exile on Main St,’ and he’s on everything else.

One of the reasons for his success is that Greg, unlike most guitar players and even most musicians, is Greg thinks orchestrally when he plays. Especially when he’s doing “King of California.” When he’s playing the Weissenborn, the wooden slide guitar that you hear on “King of California,” he’s playing it less like a guy — like if I was playing it, it’d be like, “Let me show you some licks! Da-ga-ga-ga-ga…” Greg is thinking more about what you’re talking about, capturing the essence of the song and making the song sound huge.

There is a process.

Yeah, and that’s why he gets all the phone calls to play with Joni Mitchell or Jackson Browne or whomever.

So, in what ways do you think your music has changed since King of California?

The big change was letting the song dictate how it sounded, you know? Because I had become a songwriter really for The Blasters. When we started the band, we were doing old Howlin’ Wolf and Carl Perkins songs. And then we realized to get anywhere we needed original songs, so I started writing original songs. But I wrote them for a band. When you’re writing for a band, you write a song and you say, ok, now I’ve got to make this song fit the band.

We had a style that was sort of a mix of blues and rockabilly and country and whatever else, cajun… So, I would rearrange the songs as I wrote them to fit — the band would sound good doing the song. Where with King of California, that was the first time that I’d said the songs will dictate how they sound. So you write a song, or you have a song that’s like a bluegrass song, then let it be a bluegrass song. This is a blues song. Then let it be a blues song.This is kind of between the two; let it be that.

Just let it be.

Yeah. And pick the right musicians that can do that for each song, as opposed to trying to make the same musicians play in a variety of styles. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. So if the song wants to be a ballad, it’s a ballad. If the song wants to be a rock and roll song, it’s a rock and roll song. That was the big change. So since then, through the years, that’s just always been my rule: what is this song telling me it wants to sound like?

Yeah, not to get too far off track, but it reminds me of when you were recording the last Blasters album. I thought it was interesting that Stan Lynch came in and played a percussion loop. That’s a good example of calling on the right musicians for the right effects.

Yeah, we started doing that a little bit on that album. Especially — there was a song called “Little Honey”…

That you wrote with John Doe.

Yeah, John and I wrote it together. John heard it as a rock and roll song, and I heard it as a blues song. And then, by the time we got to The Blasters, we tried it rock and roll, we tried it as a boogie number, we tried it all these ways. And then one day it just kind of morphed into this ballad. The producer made a couple of phone calls, and we made a couple of phone calls, and we got the right musicians down there and recorded as it should have been recorded.

I know you were inspired by blues artists such as Big Bill Broonzy and Big Joe Turner.

Uh huh. All the Big guys.

Yeah, you’re basically a blues guy. But who tends to hold sway in your sound as far as country goes?

You know, Merle…

Ok. Bakersfield sound?

Oh, totally. Totally. I produced some records back in the ‘90s for a group called the Derailers. We were basically just updating the Bakersfield sound. So, the actual hardcore Bakersfield sound — I’m not that good of a singer to pull it off. I’m an interpreter, you know? And I’m very comfortable with that. But Merle is certainly an influence, and Buck. That whole sort of, how do I put it, edgy.

Buck could sing!

Oh, Buck could sing.

Well, he’s not taken seriously. People talk about Hee Haw.

He figured out early on that his — because I interviewed him years ago.

Yeah, I read that.

And he told me the greatest thing, he goes, “Back in those days — I couldn’t say this, Dave, but my two biggest influences were Bob Wills and Little Richard.”

Tom Petty was inspired by Little Richard, too, so there you go.

Oh, everybody was. Buck figured out that he had to…

How to channel it.

Yeah, he had to create a character in order to market it. So, his character was the polar opposite of Merle Haggard’s. As far as other country goes, certainly Hank Williams and Lefty Frizzell and people like that, George Jones, Ray Price… The songwriting in the glorious heyday of country songwriting may be extended from Hank all the way to Guy Clark. I liked the era of late ‘60s/early ‘70s, sort of the era of drinkin’ and cheatin’ songs, the hardcore ones where they were telling stories.

Those are good vocals, too.

They’re great vocals. But I was attracted to the lyrics. I’d say another person that had a huge influence on me was Marty Robbins.

Oh, he’s one of my favorites. He was a great songwriter.

Now that is an underrated songwriter.

Yeah, he is. He’s the best interpreter of that Gordon Lightfoot song, “Ribbon of Darkness.”

Oh, yeah. Marty Robbins could sing anything.

He made that his own, you know?

Yeah, he did. And my feeling of Marty Robbins is — you know, he’s an underrated songwriter — he wrote “El Paso.” What else does he have to write?

Oh, I know. And that other gunfighter ballad…

Oh, yeah, “Big Iron.”

I love that song. Such a ballad.

When I write a song, I have two songs I judge all songs — mine or anyone else’s against — and that’s “El Paso” and “Memphis” by Chuck Berry. So, if your song can get close to “El Paso” or “Memphis,” then you might be onto something.

Speaking of country, I love that you turned a George Jones song into a duet. I would actually have a hard time narrowing down just one George song, so I guess my question is why “What Am I Worth”?

Because we had a lot of sad songs on this album. And I felt that we needed something to go, “Hey! How you doin’? You’re doing alright? You’re still with us? Life can be funny, too.” You know, I’m a goofball at heart.

Syd Scott does a pretty good job capturing the essence of George, which is not easy to do.

Yeah, we were goofy.

You’ve been playing shows with Jimmie Dale Gilmore. How long have you been playing with Jimmie?

Well, we’ve known each other for 30 some years. We had just never played together until about two, two and a half years ago. We did a string of acoustic shows. And it was about midway through the first song of the first show that I was like, “We should make a record together.” We did one last year, ‘Downey to Lubbock.’ And we’re going to do one in the next six months or so. I just love it.

Jimmie, to me, is an inspiration to play with. He went through a lot of grief in his career where they were trying to make him into a star, make him into something he wasn’t. What’s fun about now is he doesn’t care about that; it’s about doing what he loves. And that is where we’re simpatico. We have sort of the common love of folk and blues and country music. The highways are wide open for us. We can do whatever we want.

And you had the Ash Grove days in common, right? Which was an important time for you.

Yeah. Yeah, it’s funny. Like I said, I knew Jimmie for 30 years. I never knew he was at the Ash Grove when he was a young man in L.A. and my brother and I were just kids hanging out. So yeah, we wonder if our paths crossed in those days somehow.

I like his voice, kind of a Willie Nelson type.

He’s certainly got the West Texas — he can sound like a mournful coyote.

Is playing live still your favorite part of playing music?

Yeah, I live for that. Because when you’re playing odd music, which is out of the norm of a popular culture. If you can connect — if you can find the audience for that, which is a diverse audience, everything from truck drivers to lawyers. When you get everyone together in one place, a nightclub or whatever it is, there’s a bond between the artist and the audience that inspires you that makes you play better or write better or sing better. You know, you feed off that; you each feed off that. And the audience can feel — if you can make people have a reason to get out of bed, you know, that’s your job. And I love that.

This reissue features three new bonus tracks: a previously unreleased instrumental, a Merle Haggard song, and Katy Moffatt’s “The Cuckoo.” Is there anything you’d like to say about these bonuses?

Merle liked the “Kern River.” That’s what I’d like to say about it, you know? What else can you say? He told somebody that he thought it was better than his, but I think he might have been drunk or high when he said that.

How does it feel when someone sings one of your songs? John Doe, for example, when you were in X.

If anyone does one of my songs, I’m happy. I’ve heard people do them great; I’ve heard people murder them. I like ‘em all. It’s like, go ahead, murder it!

The reason I ask is because I think the harmony between John and Exene in “4th of July” is nothing short of magic.

When I was in the band and brought the song to them, John latched on to it. Both of them liked the song instantly, so it didn’t take long for them to — John is a great harmony singer.

He really is.

And he’s very good at being patient with people, with other singers. But he and Exene, they kind of latched on and came up with the harmony part fairly quickly, in my memory. It’s one of those things, occasionally you write a song that sings itself in a way. And that’s one of those songs, and I think one of the reasons it’s remained popular. One, it sings itself. You can sing it in the shower. It doesn’t matter.

Yeah, I do.

I do, too. I did, before I recorded it. Then it was off to others. So, I remember that. Having people cover or sing my songs is a huge honor. I’ve had some — you know, hearing David Hidalgo of Los Lobos singing “Marie Marie,” forget it. That’s great. I wrote a song with…

I like how you could always write songs about hard times, even during the romance and synth- heavy glamour of the ‘80s. It’s admirable.

It wasn’t easy!

Lastly, I think the most appealing thing about your music is how open-minded you are; this is the crux of the matter in terms of roots music that I don’t think everyone understands. You and Phil starting in The Blasters and appealing to that demographic of blues and folk fans, of course, and then basically having a crash course in playing fast and loud enough to appeal to the punks in the LA scene at that time— while staying true to the roots that got you interested in playing music to begin with.

Yeah, there were a lot of similarities between — one of the things I like about the early days of punk rock was the sense of community.

Yeah, even the mosh pits were…

Yeah, they were gentle mosh pits.

Civil. They weren’t going to hurt you.

Yeah, but then things got ugly. In the early days, it was a bunch of oddballs and rejects…

Who just wanted a place to fit in.

And we found each other. And so, that was a fun time.

And you were able to still send a message and convey the attitude of your folk forefathers, and not everyone can pull that off.

We certainly played, live especially, louder and faster than a lot of other people did, which kind of maybe turned off some people.

You’re never punk enough for the punk people, and you’re never blues enough for the blues people.

What can you do, huh? I don’t like being categorized. I’m basically a blues guitar player. But I’m a songwriter first. I’m like Gene Autry: don’t fence me in. I’ll kick the barn door down. I’ll escape somehow if you try to — I’m the kind of guy, if I sit in with a blues band I might do a Webb Pierce song. If I sit in with a country band I might do a Jimmy Reed song. I’m a contrarian.

Now when you tour do you find your fanbase is all walks of life? You know, as it relates to ages, interests, so on and so forth…

Uh huh. Yeah. It’s pretty much all over the place. The demographic changes depending on geographic locale. Some places where the audience is older, some places where they’re younger than me. It’s sweet sometimes when you play an all ages show. I really like when kids sneak in, because that reminds me of me.

Me too. I saw the Stones when I was seven.

Wow.

I actually started seeing George Jones from the time I was five, and then many times after that. That’s how long he’s been my favorite singer.

Well, you can pick a lot worse than George Jones.

I know, right?

Yeah. He was going to record a song of mine that’s on ‘King of California’ called “Every Night About This Time.” True story. He was going to do it. And it was decided by the record company or the producer that the song was too country for George Jones.

That’s like you sounding too much like The Blasters.

Exactly. Exactly.

Which is a really fucking great thing.

Thank you very much. I’m proud of sounding like The Blasters.