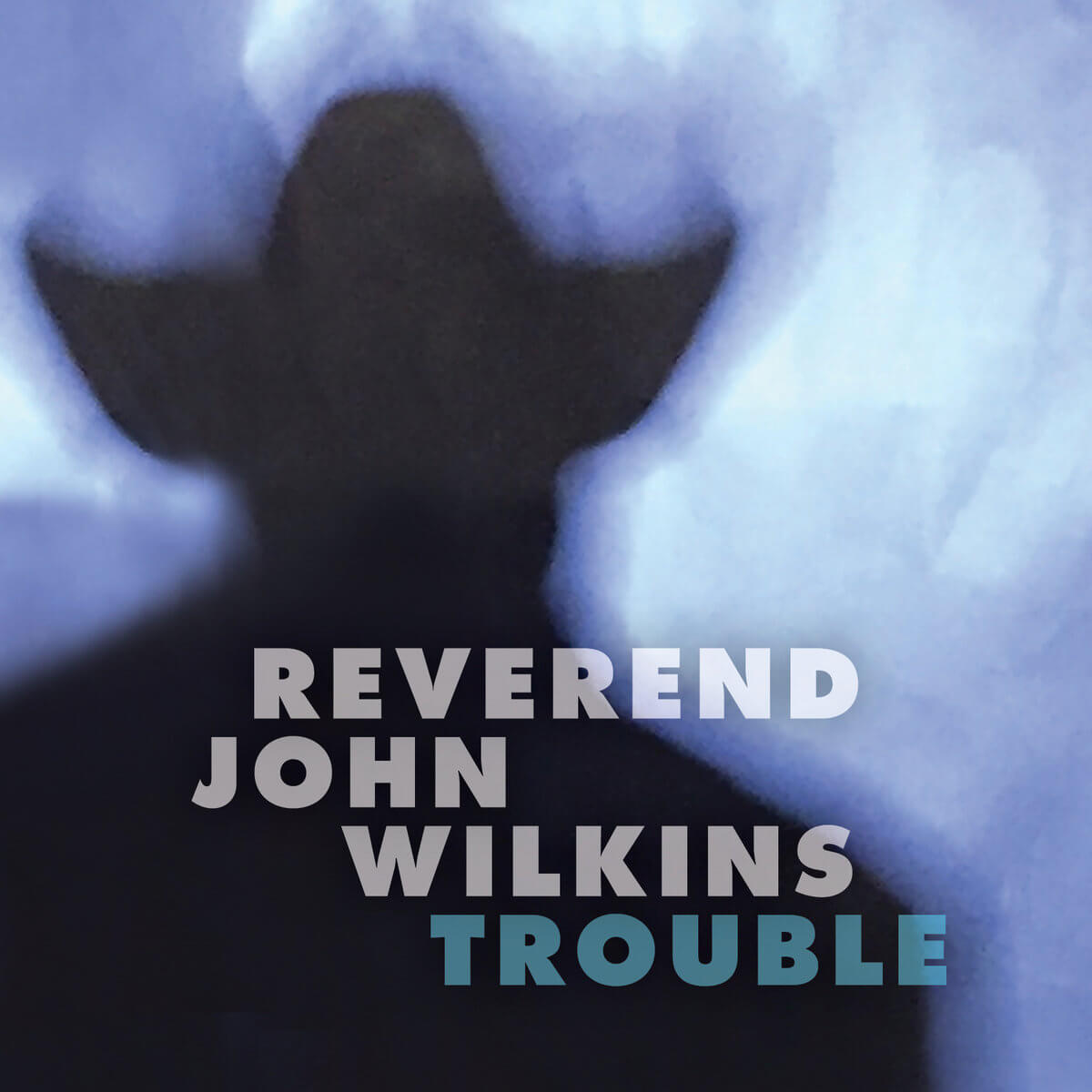

If you’re looking for miracles in a pandemic world gone mad, this is a good one. On September 18th, Reverend John Wilkins at the age of 76 will release his second ever album, following five weeks in the hospital — 17 days of which were on a ventilator. Entitled Trouble, the 10-cut release includes the prophetic song “You Can’t Hurry God,” a redo of the title cut of his first CD more than a decade ago.

You can’t hurry God

You got to wait and give him time

You don’t have to worry

He may not come when you want him

but he’s right on time.

A twist on the old saw that God moves in mysterious ways, this song written in 2010 was prescient then and “right on time” now. Not only is it a headline for our current situation – Reverend John’s recovery at age 76 constituting a miracle in the age of COVID-19 – but it’s as if the world had been waiting for a song this uplifting.

The whole album is as iconic as the best releases of The Staple Singers, The Holmes Brothers and The North Mississippi Allstars, each of whom has helped obliterate the once yawning chasm between gospel music and the blues.

Who is this miracle man The Reverend John Wilkins, and how did he pull it off? Reverend John is the son of the Reverend Robert Wilkins, best known for writing “Rolling Stone” in 1928 and “The Prodigal Son” in 1964, made most famous by The Rolling Stones on their 1968 Beggars Banquet album.

The Stones’ version was both sensual and spiritual, breaking a societal taboo at the time. Beggar’s Banquet was the creative high-water mark for “the world’s greatest rock band,” and their version of that song in particular found Jagger and the boys adding nuances to an already powerful blues/gospel crossover song. On this one cover song, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards made a significant step forward from their early reputation for doing cover versions of electric Chicago blues. This was the first time in their five-year career that they cut an acoustic delta blues song with a message so antithetical to their bad boy image.

Wilkins was 17 when his dad recorded “The Prodigal Son.” Just as John’s 2020 version of “You Can’t Hurry God” is a redo, Dad’s “The Prodigal Son” has the same melody as his “That’s No Way to Get Along” from 1929 with new lyrics. The reworked lyrics were inspired by a New Testament parable in the chapter of Luke. Its message is akin to the golden rule: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. The older of two sons leaves home even though his father had showered him with gifts. His younger brother remains true to his dad, but when the older sibling returns his father rejoices:

And I’m so glad lost son home to me

my son home to me

So glad my lost son home to me

So glad my lost son home to me

And that’s the way for us to get along

Did Reverend Robert see himself as “The Prodigal Son?” George Wilkins – Robert’s father and John’s grandfather – had left the family when Robert was only two in the year 1900. It was Robert’s stepfather, Tim Oliver, who taught Robert how to play guitar, and early on Robert took the surname Oliver only to later change his name back to that of his biological father. In so doing, Robert truly was a prodigal son returning to the nest.

History is repeating itself. Reverend John Wilkins’ “You Can’t Hurry God” mirrors his father’s message on “Prodigal Son,” in that it’s an anthem with a Biblical message and a back story of hope for a civilization searching for miracles.

Robert had become an ordained minister by the time John was seven in 1950. “I remember when he was going to church,” says John. “I’d have my little guitar, and I was right there on the stage. Every time he’d get up, then I’d get up.” Ten years later, Dad released the revamped song with lyrics inspired by a New Testament parable.

“The Prodigal Son” first appeared on Reverend Robert’s Memphis Gospel Singer LP released on Piedmont Records in 1964. He sang that song and two others at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival. By 1968, he was 70 years old and only played close to home until his death in 1987 at age 91. The Rolling Stones’ cover of his song had minimal effect on his career.

In the 1970s, son John performed and toured with the M&N Gospel Singers. Since 1983 he has pastored Hunter’s Chapel Missionary Baptist Church just outside Como, MS. His church has been home to many players in the North Mississippi fife and drum tradition, including fife players Otha Turner and Napoleon Strickland (the latter of whom is buried in the church cemetery).

By 2006, Reverend John had retired from his day job at the Memphis Parks Dept. and gone into music following in Dad’s footsteps. Until the pandemic hit, Rev. John split his time between the church and fronting a national and international touring band along with his backup singing daughters Tangela Longstreet, Joyce Jones and Tawana Cunningham who enjoy a strong presence on Trouble. The pandemic has put any touring on hold.

The album is breathtakingly beautiful, filled with messages of hope that present a menu of sanctified sensuality masterfully produced. Rev. John’s prophetic vision of the world is exquisitely presented.

Trouble marks the first time he’s worked with “the house band” at Royal Studios. “Yeah. I was singin’ it before the studio band got with me. My original band was tied up, so Boo (Lawrence “Boo” Mitchell, engineer) got the studio band playing.” The sessions went smoothly and quickly. “Oh, man, they went down ’cause I had it together, you know what I mean?”

The title cut references today’s troubles in the White House and troubles in the schools, but was written and recorded before the pandemic. “That’s right,” says Reverend John. “It means more to people now than when I recorded it. It gives people something to think about.” He calls the album a blessing because “I didn’t know I was going to go through that stuff.”

His three daughters are his backup singers who travel with him. They range in age from 47 to 57. “Yeah, I had ’em together, and my daughter Tangela, she’s a great lead singer. They used to be the Violinettes. After they broke up, I got them on with me.”

They are prominent in all the cuts and remind me of the energy and charisma of the background singers on the Stones’ “Gimme Shelter.”

Other originals on Trouble include “Down Home Church,” “Walk with Me,” “God Is Able,” “Found Love,” “I Got Something” and “Storm and Rain.” Reverend John also does righteous covers of Bill Withers’ “Grandma’s Hands,” Ralph Stanley’s bluegrass classic “Darkest House” and The Fisk Jubilee Singers’ “Wade in the Water.”

Trouble was recorded last year at Royal Studio in Memphis. One of the oldest perpetually operated recording studios in the world, Royal was the home of Willie Mitchell who produced Al Green hits that include “Can’t Get Next to You,” “Tired of Being Alone” and “Let’s Stay Together.” Between 1970 and 74, Hi Records released four number one hits for Al Green, more than Stax artists Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, and Booker T. & the MG’s achieved during their entire combined careers.

Stax and Sun Records, the two other iconic Memphis labels, may have higher visibility than Hi Records, but it can be argued that Hi’s impact on the American pop canon is of equal significance. To this day the studio continues to host gold and platinum selling artists such as John Mayer and Rod Stewart.

Willie Mitchell’s son, Lawrence “Boo” Mitchell, engineered Trouble. His credits include Al Green, Rod Stewart, Cody Chesnutt, and 8 Ball. Supporting Rev. John on this release is B3 organist Reverend Charles Hodges, one of Memphis’ most seminal creative forces. His feathery light touch for more than 60 years has enhanced releases by artists as disparate as Al Green, Ike and Tina Turner, Albert Collins, Tom Jones, Bonnie Raitt, Keith Richards, Boz Scaggs and Vanessa Collier. His spiritual muse is one of the hidden secrets behind the development of Memphis as the home of soul music.

Besides John Wilkins himself, the other guitarist on Trouble is Kevin Cubbins, the executive producer of the PBS syndicated radio show Beale Street Caravan where he has worked with B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Pinetop Perkins, and Hubert Sumlin to name a few.

Trouble is a ray of sunshine in the world’s darkest hour. It pushes the needle a step further in disproving the contention that blues is the devil’s music and the yin to gospel’s yang. The elemental truth is that both genres offer a catharsis. Both are celebrations of life and the conquest of good over evil. And both celebrate the gift of life from God who ultimately decides when and if things are going to happen.

Pre-Order Trouble

Reverend John Wilkins Facebook

*Feature image photo credit: Adam Smith