Elvis Presley, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and Willie Nelson have each built a reputation in part as a result of covering his songs. Billy Joe Shaver may never have attained their success, but his contributions to the popular music songbook will long be remembered. Country songwriter Billy Joe Shaver died at 81 on October 28, 2020 following a massive stroke.

His song “Live Forever” was co-written by his son, Eddy, who died of a drug overdose on New Year’s Eve, 2000. It was performed by actor Robert Duvall in the film Crazy Heart.

Shaver always told the truth in his songs ’cause he had nothing to lose by lying. Willie Nelson talked him into performing on New Year’s Eve, 2000 at Poodies outside of Austin, the same day Shaver’s son Eddy died of a heroin overdose. He was on stage the night his mother died and also performed the same day he was acquitted of murder in 2010 after shooting Billy Bryant Coker in the face in a bar in Waco. He later wrote a song about it, “Wacko From Waco.”

Christmas came early in 2012 when Billy Joe Shaver played Troy, New York’s Ale House on a Tuesday in early December. Part roadhouse, part 19th century Charles Dickens pub, The Ale House is a local roots music nirvana — the perfect venue for this, and one of the best roots music shows I’ve seen outside of Chicago and north of the Mason-Dixon line.

A living embodiment of The Picture of Dorian Gray, Billy Joe gave himself so completely to his music that the pain of his rough-lived 81 years was completely forgotten when he was on stage. “My knees and stuff are going out,” he told me in in a 2012 interview. “My back’s gone out, and both my shoulders have gone out, and I got screws in ’em, and I got one new knee, and I’m needin’ now to get another new knee, and, oh, just things that gave up from wearing yourself out.”

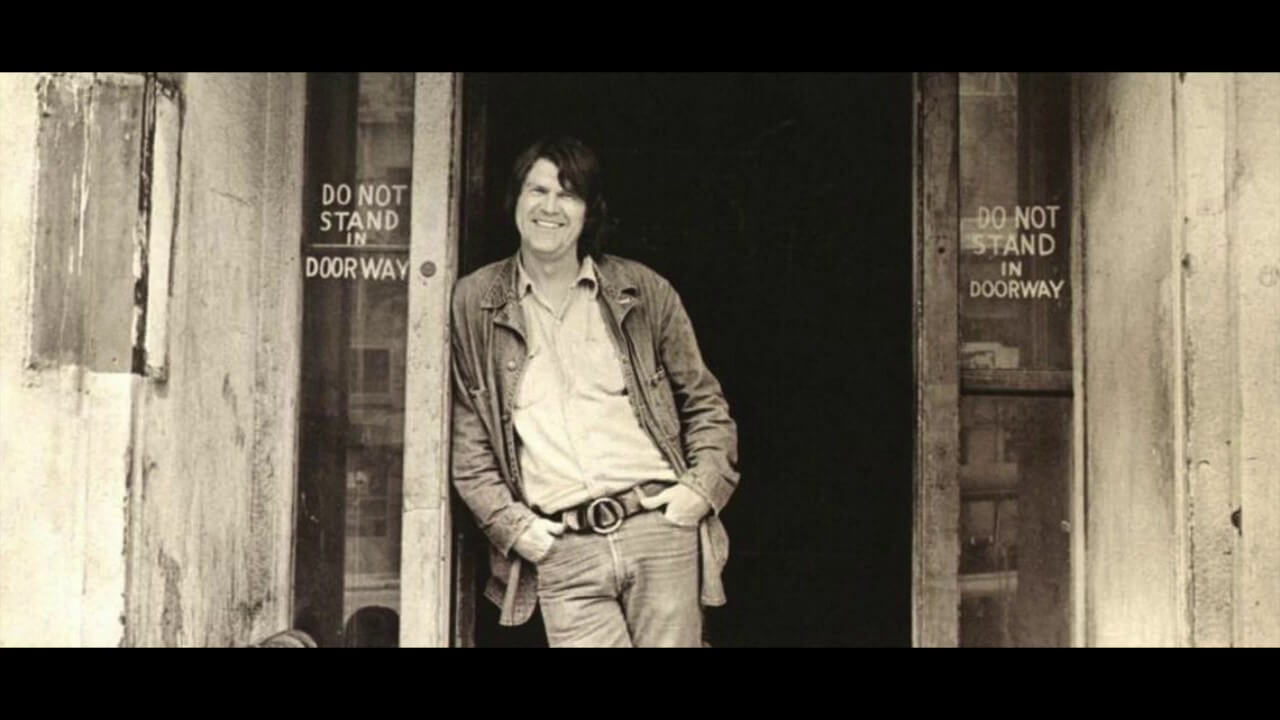

But on stage he gave the walking dead a bad name. He may have looked like a zombie, but he performed like a teenager possessed the night I saw him at that packed pub in North Troy. He wore denim like skin on an alligator that clung to his beat-up bones as the sweat of a two-hour song fest marathon soaked into his shirt. A Christian cross and a tiger’s tooth hung from his neck, and he lifted his weathered and feathered brown hat to reveal thinning white hair that corkscrewed around his skull like a baby chick’s fuzz until he swept it back with his hands, his right hand reduced to stumps with his first three fingers severed in a sawmill accident.

Moving in erratic dances in time to the band and occasionally lifting his arms to the sky and bellowing like Sitting Bull at Wounded Knee, he looked over the audience like an ancient mariner surveying the horizon, his intense fixation in search of a sliver of land and the promise of a safe port of call.

Waylon Jennings may have been the most famous of the country outlaws, but Shaver wrote the title song of Waylon’s 1973 Honky Tonk Heroes album: “There weren’t another other way to be/For lovable losers, no account boozers/And honky tonk heroes like me.” Billy Joe wrote nine of the 11 the other songs on that LP that became the template of the country outlaw trend that Billboard magazine summed up as “a back-to-basics 1970s movement that included Willie Nelson, Kristofferson, Merle Haggard, Johnny Cash and a number of others.”

Outlaw country is a term invented to sell twang to the gang. Like the Robert Johnson myth that that bluesman sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads, outlaw country was a clever hook invented to seduce young rockers into a genre that most of them turned their nose up to when it was coined. Some of the practitioners earned their Ph.D. (prisoners held in detention) behind bars, but the artist most deserving of the title was Billy Joe Shaver.

Billy Joe’s dad beat his wife so badly when she was pregnant with him that it’s a miracle he was born. Brought up by his grandmother, Billy Joe only made it through the eighth grade before he had to go to work to keep food on the table. He married the same woman three times, the last time to nurse her to her death by cancer. The only consistency in his life was his songs. In fact, he says songwriting has saved his life.

“I knew what I had when I was young. I started talkin,’ I started writin,’ makin’ stuff up in songs, you know. Or listening to other people singing what they’re singing. It just came to me. I just assumed it was a gift from God, and I was damn lucky to get it, and that’s the way I treated it. I’ve done the best I could with it, and if it’s a gift from God, then I’m lucky to have it.”

“I’m Just an Old Chunk of Coal (But I’m Gonna Be a Diamond Some Day)” covered by Johnny Cash was a very special song to Billy Joe. “I was born again during that song. The first half of it I got born again, and then the second half took me six, seven, eight months like that to write ’cause I went cold turkey, didn’t do any drugs or smoke or anything or drank. I couldn’t keep anything down but Melba toast, diet root beer, and that was it.”

God helped him through.

“I just kept on praying every day, pray and pray and pray. Actually, what happened was I went up on that mountain up there and I thought I’d jump off, but I wound up on my knees at this alter-type thing and wind or rain or something came out. It was the middle of the night. I was up at four in the morning. Wasn’t no stars out. It was Friday night, and it was hard to see, but everything was glowing to me, and I don’t know if it was in my head or not, but there it was, and when I got through up there, I can’t tell ya about all that because it takes so long, but I started singing “Old Chunk of Coal.”

“By the time I got to the end of the path I had the first half written. The old man that I was died, and a young man took over, because the old man was good enough to die for me ’cause he knew that to die everything with him died, all that sin and everything.

“I saw a vision in my house when I walked in, a vision of Jesus Christ on the end of my bed doing his head sideways with his hands on his chin and like, ‘How long are you gonna do this?’ And I glanced toward him, and I couldn’t look him in the eye ’cause his eyes were like coals. This was the vision I had. If you wanna say I was lyin’, go right ahead. I don’t care. That’s why I went out to this place where my son had showed me, and that’s about it.”

John Anderson had the hit with the song, and Cash recorded it before him. “He loved it. He actually said he went into rehab, and every morning got up singing that song. It helped him through it.

“I’d just make up songs, but I went on through life and worked and lost my fingers and broke my back and did a whole bunch of stuff. I rodeoed a while. I (worked on ranches) and everything about a cow I know, and any kind of cattle as a matter of fact, horses and stuff. I used to break ’em out, but never was no problem with me, but I ended up hurtin’ myself quite a bit ’cause I always throwed myself into a job real hard. Whatever I was doing, I would go full bore through the hills. And I’m kind of paying for it now.”

Billy Joe played guitar in spite of losing parts of three fingers in a saw mill accident. His album, Live at Billy Bob’s Texas, includes originals made famous by everyone from Willie Nelson and Johnny Cash to Kris Kristofferson. “Georgia on A Fast Train” alone (on that album) has been covered by Tennessee Ernie Ford, The Allman Brothers, Johnny Cash, Dickey Betts and Great Southern, Commander Cody & His Lost Planet Airmen, Twangbangers, Two Cow Garage, and 17 others.

Hearing the songs live vs. his then current CD, Live at Billy Bob’s Texas, in 2012 was to view the Titanic movie in 3D for the first time. Shaver didn’t create songs so much as his songs created him. The antithesis of drugs that numb pain, his musical forays devoured and showcased his pain. A seasoned troubadour, he delivered the message that God is a loving entity with a sense of humor, and that life itself is a gift that wrenches the bad times into perspective.

“They didn’t like my daddy,” he told me at the end of our interview. “My uncles and all didn’t like my father. Well, he’d whipped most of ’em actually, but I didn’t know a lot about that stuff. All I knew is they didn’t like him, and way back yonder the way people were about you or your father, they thought you’d be just like him.”

Then, he stopped himself realizing he’d been on the phone too long. “I sit here and let the bank close. Checks to cash!”

There was a click on the line, and he was gone.

But he called me back a few minutes later. He wanted me to know that everything he’d told me was the truth.

I believed him. And he will call me back through his songs until I, too, am gone.

*Feature image: Jason DeCrow/AP File