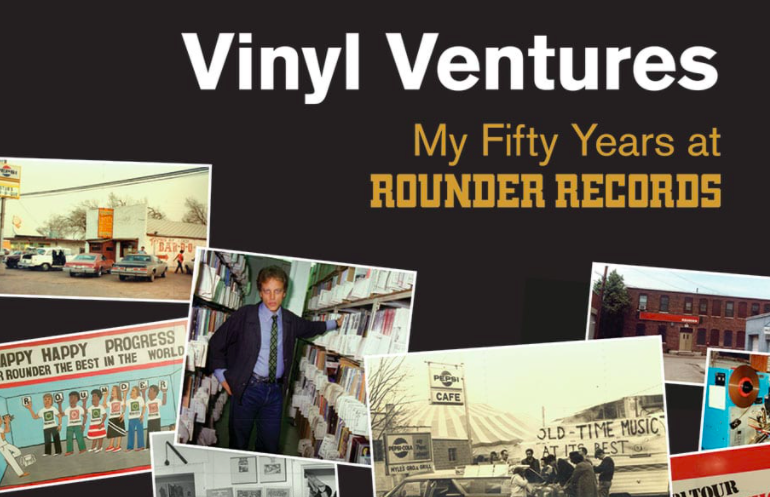

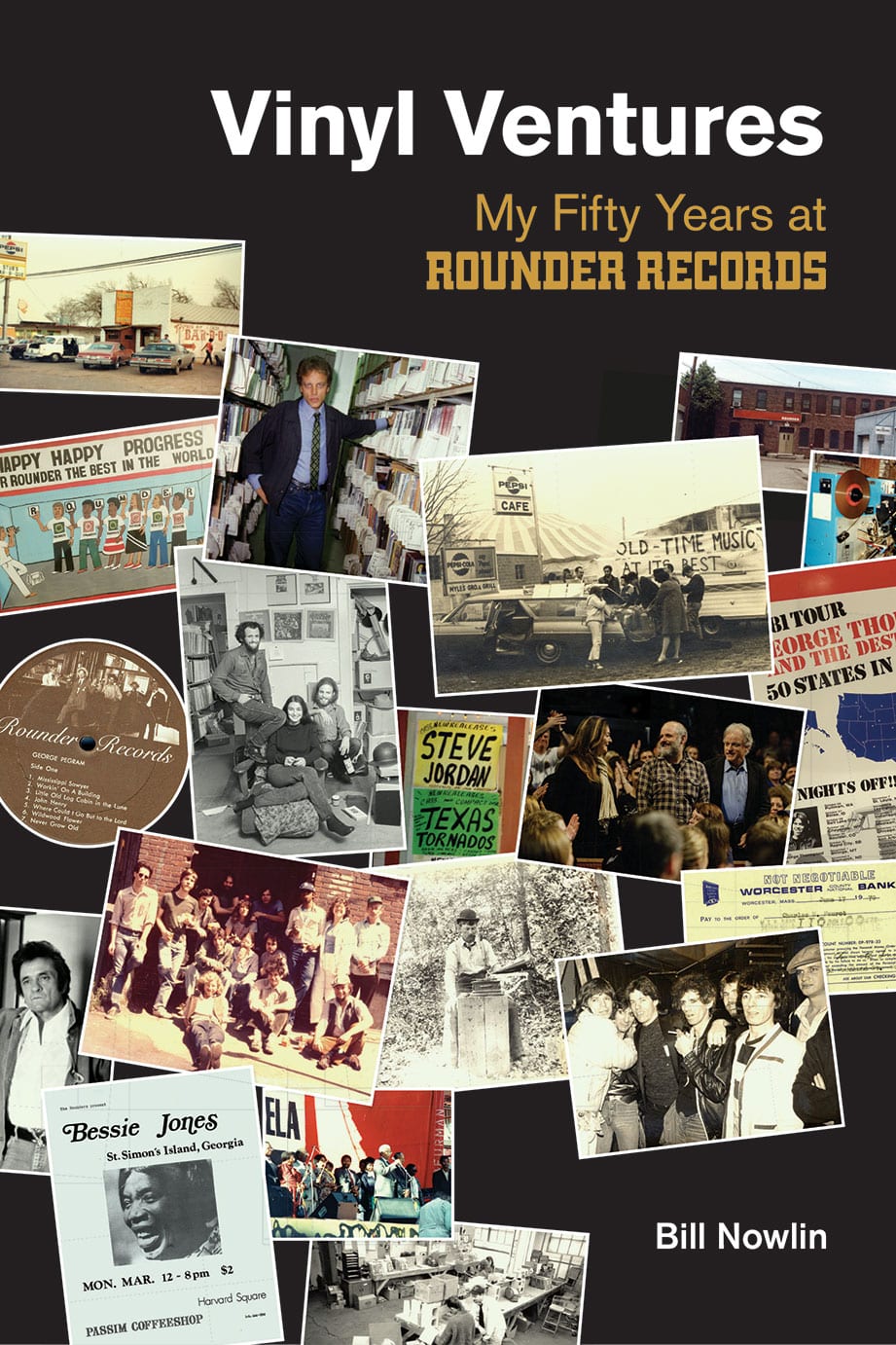

Bill Nowlin is a multi-millionaire who still returns bottles for the 5-cent refund. He’s written and/or co-written 102 books about baseball while in “retirement.” And he’s just released a 300-page memoir Vinyl Ventures, My Fifty Years at Rounder Records — published by Equinox Publishing Ltd with more than 20 pages of footnotes and other data about his 50-year odyssey as one of three partners who turned Rounder Records from a tiny record label releasing albums by artists no one else would sign into the largest independent label in the world.

Along with his partners Ken Irwin and Marian Leighton, Nowlin built the world’s most prolific and unique indie record label. And, oh, by the way, he introduced me to the Boston coffeehouse scene at Tufts University when we both were students.

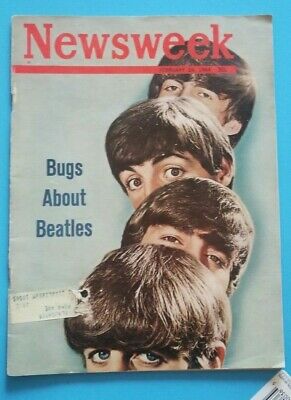

We were teargassed together splayed on the hood of the Stones’ limo in ’65, and we made the 1964 issue of Newsweek magazine with The Beatles on the cover for our American Tissue Games Association high jinks.

The article “Silly Seasons” told of our competitions unrolling 1000-sheet single ply Scott’s toilet paper for time. We even had a gold toilet with a queen who sat on “the throne” with her scepter, a plunger!

As a child, Nowlin made lists, lots of them. “I just liked those lists: the longest river in the world wasn’t a secret. You could just look it up in the encyclopedia, but for some reason that fascinated me. So, I would go write Amazon, number 1, and it’s 2,040 miles long or whatever it is. I’d write down number 2, and all I was doing was copying it out of the encyclopedia. Somehow, this thing and ranking and so forth appealed to me.”

Knowing his predilection for lists helps explain his attention of detail in Vinyl Ventures walking the reader through a half century of building a label that began with two album releases in 1970 on an investment of $1000 to a corporate behemoth half a century later when the trio sold the label to Concord Records in 2012, after releasing albums by everyone from Woody Guthrie to Bela Fleck. He’s never actually counted the number. In that period the label earned 56 Grammys.

The city of Cambridge, Massachusetts in a 2007 resolution described Rounder this way: “This untested trio went the distance from humble beginnings over thirty years ago to what is now America’s premier independent record label. From its early interest in rural American music (via fiddle, stringband, blues and bluegrass recordings) to an expansive catalogue of more than 3000 titles running the gamut from folk to world, soul to socas, jazz to juju, Cajun to Celtic, and beyond, Rounder has emerged as the preeminent source for vital, uncompromised music of all genres.”

“It wasn’t as though we were academics who were only interested in documenting music that otherwise wouldn’t get documented,” Nowlin tells me. “They were just groups that we liked. There were a lot of bluegrass groups. There were an awful lot of standards that they worked into their repertoire: Bill Monroe, The Stanley Brothers, Flatt and Scruggs and modern groups, too. They were good musicians, and we enjoyed working with them as people. There isn’t (just) the archival aspect of some of the stuff we did.”

I can remember Bill taking me into this dive in downtown Boston called The Hillbilly Ranch to see The Lily Brothers. We were rubbing shoulders with Navy men on leave and prostitutes while listening to one of those unsung bluegrass bands Rounder would later record in 1977. We were under age, but they let us nurse ginger ales while the band let fly on a stage bookended by wagon wheels.

“We wanted to follow in the footsteps of somebody like Alan Lomax,” explains Nowlin. “He may be in a more commercial way by getting it out in the marketplace as opposed to putting it in the library of Congress or those types of institutions that would preserve it, but I just wonder, if I were to go someplace with the goal of finding (undiscovered) music (today), would I find music there that was distinctive and different? And how much so?”

I tried to talk Nowlin into signing Roy Buchanan, but when he hanged himself three days after giving me an upbeat interview in 1988, I realized any hopes I had of becoming Rounder’s A&R guy were futile.

“We were almost more inclined to record people whole never performed in public, in order to document their creative work before it disappeared,” admits Nowlin in his memoir. “We weren’t taking a penny, and didn’t pay ourselves a salary at any time for the first four years.”

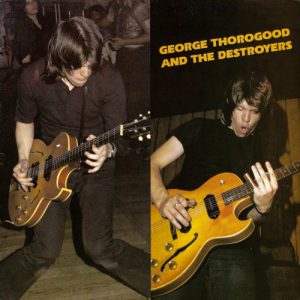

Seven years into their business, Rounder signed George Thorogood who advanced the label from “a hobby that got out of control” to a serious indie contender, this after Delmark Records CEO Bob Koester credited them with “transitioning from hippie radicals to young hustlers.”

Nowlin talks a lot in the book about George Thorogood and the Destroyers, the first signing in 1977 that made the label real money. “Obviously, the band is different than all the others, but not necessarily in a category all by themselves,” says Nowlin.

“I just laid my cards on the table,” says Thorogood about signing with Rounder. “I said, ‘This is what I do. I’m very good at it. Are you interested or are you not?’ And they said, ‘Let’s put out a record and see how it goes.’ That’s what we did.”

Thorogood remembers the negotiation. “They said, ‘Look, this is where it’s at with us. We’re a bluegrass label. We’re a very small independent label. People buy catalog through us. We don’t have major distribution.’ I said, ‘Don’t worry about that. Let’s just get the record out there. I need the record out there.’ I don’t want to do auditions anymore.

“I begged. They did not ask me. Trust me. (Rounder is) a bluegrass label. They don’t know anything about rock. They don’t know anything about Led Zeppelin or Billy Gibbons. It’s a bluegrass label. My only shot was Alligator Records, and Bruce (Iglauer, Alligator CEO) told me that he wasn’t interested in me because we weren’t an authentic blues band, whatever that means.”

Plus, Nowlin and Thorogood share a love of the Rolling Stones and baseball. “I’ve never given up my love of baseball,” says Thorogoood. “However, the major leagues did not care for my style. (Laugh) I knew at the age of about 16 that I was going to have to do something else for a living, and that just seemed like the natural way to do.

“I first thought about (getting into music) with the Rolling Stones’ first album, and I wanna tell you why, ok? I said, ‘These guys are neither beautiful, and they’re not great singers, and they’re not writing it, but they’re there. There’s hope for me.’ That’s what made it to me seem possible. George, there’s a chance for you, a slim chance, but still a chance. And as long as you have even a slim chance, Don, you still have a chance.”

It just may have been Nowlin’s quirky sense of humor that created his bond with Thorogood. It certainly had nothing to do with ego for either of them. “I’m just out to appeal to the people that go for what I do, Ok? I’m a knock-knock joke,” admits Thorogood. “But I’m the best at it, ok? The only way I got through junior high school or high school is by cracking jokes. Comedy was my first love when I was 12 years old. I had like 300 jokes in my repertoire. Music came along, and I said, ‘Why don’t you combine the two? If you can get people to dance and laugh at the same time, you got something. You got some going.’ And my music is funny. Figuring out my band is like trying to figure out the plot to a Three Stooges film.”

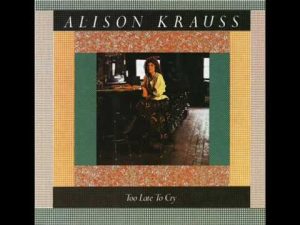

It was Allison Krauss who made millionaires out the Rounders. “Ken was the one who ‘discovered’ her,” says Nowlin. “Put that in quotation marks. She was a vocalist. She played the fiddle. You wouldn’t necessarily know that, but it was her voice that caught Ken’s attention with a vocal bluegrass band in southern Illinois. She was from Champaign, and I think she was 13 or 14. I might put on two or three tracks, (but) Ken would listen to five or six tracks all the way through. I think she might have not showed up until the fourth or fifth track, but all of a sudden, he heard her voice, and that’s what caught his attention.

“She was 13 or 14. She was definitely a minor. The contact had to be with her parents. She couldn’t sign it herself. We did have an awful lot of (young) people. Mark O’Conner was 12 or 13 when we first signed him. Current (bluegrass) artist Sierra Dawn Hull was 13 or 14 when we first signed her. There have been a few others, too. Bela Fleck was still a teenager. So, it was a thing that happened, but it wasn’t part of a youth initiation or anything like that.”

Rounder was created by a trio whose obsession with the heart and soul of music in 1970 was the antithesis of trendy. Vinyl Ventures, like so many Rounder albums, is an exhaustive collection of data about three people who in the mid-’60s didn’t like the idea that Vanguard and Elektra Records were dropping their core business of recording the folk music trend. They and other labels were moving on to electric artists like The Doors, Love, and Country Joe and The Fish.

Ken Irwin in 1965 gave me his ticket to a Bob Dylan concert in Boston where Dylan’s second set was plugged in, and he was booed by some in that audience. The Rounder trio liked their music unplugged. But they recognized the difference between commercial, common denominator rock and roll and the primal scream of acts like George Thorogood and Brits who proclaim, “It’s only rock and roll, but I like it, I like it, yes, I do.” And they helped me discern the difference to become a music journalist who has made my own long list of more than 7,000 artist interviews.

Order Vinyl Ventures: My Fifty Years At Rounder Records by Bill Nowlin