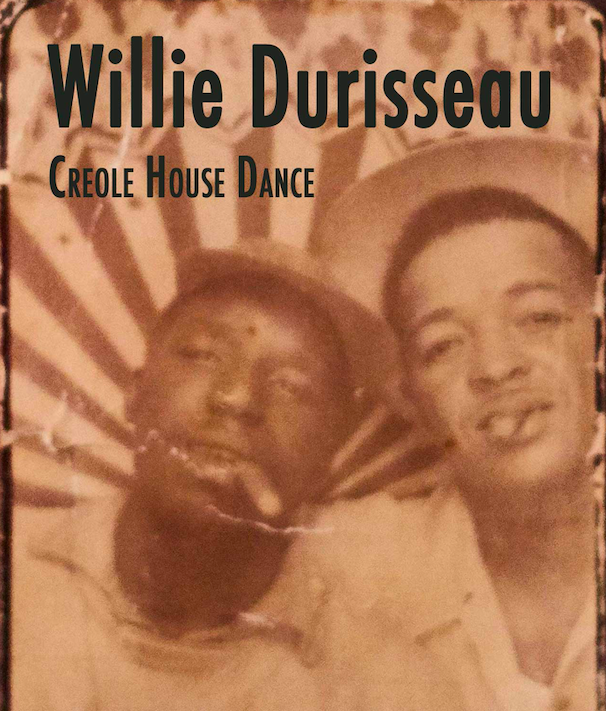

A once-in-a-lifetime moment has lent itself to a rare release called Creole House Dance, being issued via Nouveau Electric Records on June 19. Featuring 101-year-old Creole fiddler Willie Durisseau, some of the songs on the album represent a pre-WWII Creole fiddle style never recorded before. At the helm of this time capsule is Louis Michot, who captured these special performances on a Zoom stereo recorder at the Durisseau home in Spring of 2019. Willie passed away just months later.

Perhaps best known as the fiddle player and lead-singer for the GRAMMY-winning Lost Bayou Ramblers and member of Poguetry (a project with original Pogues Spider Stacy and Cait O’ Riordan), Michot is the founder of Nouveau Electric Records. His other projects Michot’s Melody Makers (with iconic producer Mark Bingham), Soul Creole (with wife Ashlee and Zydeco king Corey Ledet), and Le String Noise (with Leyla McCalla and violin duo String Noise) fill his multifaceted days.

To look at Michot’s musical journey, you must seriously consider his encyclopedic cultural knowledge, of which he is a wellspring. His detailed essay Willie and Irma Durisseau: Creole House Dance Music alone is a dissertation on Louisiana French music. He begins by writing how the Creole fiddle gave way to the Zydeco accordion.

“The fiddle, in general, has been around a lot longer in Louisiana music,” Michot explains to me. “The accordion wasn’t introduced to south Louisiana until it was popular and accessible. But before then — in Cajun, Creole, and Louisiana French music — fiddle was the main instrument for a while. And then the fiddle kind of dropped out of Zydeco; where in Cajun, it became accordion and fiddle. What started as a Creole fiddling tradition went to a completely Zydeco accordion tradition along mostly the African-American side, the Zydeco side of French Louisiana.”

One of the many unique features of Willie Durisseau’s music was that it was played at bals de maison, or Creole house dances. In the ‘30s, these weekend affairs starred fiddles and guitars. The accordion was ubiquitous elsewhere, already prevailing by the late ‘20s. Essentially it marked the end of the fiddle propelling most of the melodies forward. It’s almost as though Willie didn’t even notice, because what he did was play even older music.

“Even at that time in the ‘30s he was playing forgotten music in that sense. Amédé Ardoin was playing not long before then. He was playing accordion; everyone was playing accordion. There were still fiddles, but accordion was already King. Willie represents something that much older.” What’s more interesting, and what Michot calls a double bridge to the past, is that the skill lay dormant in Durisseau for nearly 80 years.

It was in the late ‘30s when Durisseau played fiddle with his brother, Jimmy, in their native Lebeau, Louisiana — not far from Opelousas, St. Landry Parish, home of Zydeco. When Willie returned home from war, he played a few house dances. But it wasn’t the same as before. Fast forward to just a few years ago when one of Willie’s children told Michot she didn’t even know that he had ever played fiddle.

So why set it down for all those years? “It’s a pretty big trend, probably in a lot of traditional musics, but definitely around here — for a man or a woman to play music early in their life and then put it down to raise a family.” 14 kids in Willie’s case.

“I played with people in the past, like Ray Abshire, who I mentioned in the article. He put it down for a while. And when they come back, they bring these super old melodies. That’s a whole ‘nother thing, because you have to get them right when they come back, before they forget it and relearn new stuff.”

This is the part of the interview where Michot and I learn we both have a 3-year-old and a son named Julian, and commiserate over the emotional decision to put a child in daycare or preschool. “It relates to the story because I made a cold call, and I happened to find this perfect situation down the road,” he says of finding his son’s caretaker. “And this lady is like, ‘I’m going to help you out.’ She’s certified. She goes to church with Goldman Thibodeaux, who I play with and whose record I released. I was about to ask her if she knew about Willie Durisseau. Before I could, she said, ‘My daddy’s name was Julian.’ Like my oldest son’s name. ‘I didn’t even know he played fiddle until a few months ago. He’s long gone.’ One of her siblings or cousins told her.” It turns out that she is a Durisseau.

Willie returning to fiddle at age 100 is a prime example of what distinguishes Louisiana from swampland: an artistic and linguistic affluence that exists just below the surface if you bother to scratch it. “It’s everywhere we look, even if we don’t see it — the French is, and the music is. And you have to ask to know. We’re fearful, and rightfully so, of losing the language and losing the things that go along with it. It’s important, because without being able to make those connections, it’s a lot easier to lose track of it and let it fall into obscurity.”

On the news one day was Herman Fusilier, local DJ and writer, meeting with Willie Durisseau. Michot was so fascinated by Durisseau’s melody that one of Herman’s recordings from that day ended up on the Creole House Dance record. “Willie could only play for about a minute at a time, so four or five minutes of space was like a whole album. My friend called me a few months later and said, ‘We’re going to visit him and we thought you’d be the perfect person to speak French with him and talk about fiddle.’ “

Michot brought along son Marius, who was one at the time — possibly the world’s largest age span of 1 and 101 in the same room. It warms my heart to learn that it proved more inspiration than distraction for Willie. “I have a recording of Marius wanting to play my fiddle, and that was what kind of pulled Willie to play some more. So I have them playing together. While Marius is playing, I’m helping him. He loved him; he really brightened him up. He played the longest when Marius was around. The next time, I didn’t bring Marius and had a harder time getting him to play.”

J.B. Adams, local French speaker, first took notice of Willie watching him play at a family reunion. Adams brought Zydeco star Corey Ledet along to the Durisseau home for the 2019 interviews with Michot. “It was perfect. I didn’t even know Corey was going to be there.” Michot started Soul Creole with his wife and Ledet back in 2012. “Those two are amazing at singing all the songs. He and I both know the same melodies, and she does, too, in French. She’s a French teacher, and it’s a really interesting trio. It’s a constant flow of all kinds of material, and you’ll never know what we’re going to play. We don’t even know what we’re going to play; we just follow Corey.” Michot also produced the recently released Corey Ledet Zydeco with Ledet.

There have been so many fiddle players who play what we know as Creole Zydeco. But according to Michot, Willie was the only one who played in that particular niche — unheard of and unaffected in the eight-decade interim. “That’s why it’s so beautiful. It’s so mysterious, because he’s 101 bringing that out and you think, ‘What was it like when he was in his prime, and why is there no other recording exactly like this?’ Just a completely different repertoire; he’s bringing back such an ancient sound and over a hundred years of memories.”

Snippets make up the entire performance of Creole House Dance, small songs that Michot named himself as they didn’t even really exist. “Blues à Durisseau” earned the name for its general blues rhythm as it relates to Louisiana French music.

“It’s like nothing I’ve ever heard, because at times it hints at a few old songs you hear on the Lomax recordings or something like that, but really it’s its own thing. “The other one, ‘Willie Zydeco,’ I named because I asked him what he called it. He said, ‘This is Zydeco.’ ” He only remembered it as a song he played with his brothers.

On April 10, 2019, Willie’s mind, as well as his fingers, recounted those fond memories of 1930s house dances. In Michot’s essay, he recalled Irma repeating how life moves too fast today. They had everything they needed to be happy at a time when entertainment didn’t even have a literal outlet. He tells me he dedicates this album to Irma. “They took care of each other every day. I even got myself a little portable 45 player. They haven’t been taking visitors yet, but I can’t wait to go play it for her.” I’m not crying. You’re crying.

Creole House Dance will be released as a 7-inch 45rpm record or digital download, and will be available via streaming platforms. Pre-order here.