Ben Vaughn grew up in the Philly area on the Jersey side of the river. At age six, his uncle gave him a Duane Eddy record that forever changed his life. In 1983 he formed the Ben Vaughn Combo. The band was together five years, releasing two albums and touring the U.S. several times. They received reviews in Rolling Stone and People magazine as well as video airplay on MTV. The attention inspired Marshall Crenshaw to record Ben’s “I’m Sorry (But So Is Brenda Lee)” for his Downtown album.

Ben embarked on a solo career from ’88-’94, recording four critically acclaimed albums and touring extensively in Europe and U.S. He made a name for himself as a producer, producing Memphis Rockabilly legend Charlie Feathers, Fort Worth Gospel saxophonist Vernard Johnson, and Muscle Shoals country/Soul singer Arthur Alexander. He also recorded Cubist Blues, a collaboration with Alan Vega (Suicide) and Alex Chilton (Big Star). During this time, Vaughn also scored two films (Favorite Mopar and Wild Girl’s Go-Go Rama). In the mid-90s, Ben moved to L.A. and released Instrumental Stylings, an album of eclectic instrumentals.

As a T.V. and film as a prolific score composer, he composed the themes for the award-winning T.V. sitcoms 3rd Rock From The Sun, That ‘70s Show, Men Behaving Badly, Normal, Ohio, Grounded For Life, Psycho Beach Party, The Independent, and Scorpion Spring. Vaughn has produced records for Ween, Los Straitjackets, and the Swingers soundtrack. Also, Ben produces and hosts The Many Moods of Ben Vaughn, a weekly, hourlong eclectic mix of music featuring rock, blues, jazz, folk, soul, R&B, country, and bossanova.

ABS: What are you currently working on?

I have a new record coming out for record store day called ‘The World of Ben Vaughn.’ It’s eleven songs that I recorded and I play all of the instruments including a twelve-string guitar in the Lead Belly tradition. It is something that I have never really done before and I have never really wrestled with the instrument. It is a monster when you want to really fly around and play some lead. You can’t just pick it up and do it. You have to work out for a while. It really is a physical undertaking to sound the notes the way you want to hear them hit.

With the double strings, you never know what you are going to get. You have to strengthen and readjust your hands to get good on it. I play banjo, bass, drums, keyboards, and harmonica on the record. Record store day invited me to take part this year. I was thrilled because I had the songs written, and then I had a deadline. I realized I had to record and get to the pressing plant. It was great to have a looming deadline.

Who are your blues influences?

Lightnin’ Hopkins. He is the first guy I heard that I realized I could play note for note. I don’t know how to change on bar nine though. He plays eleven or thirteen bar blues depending when he changes. It always surprises me. I had the math beaten into me too much to be able to play exactly like him. I can’t escape my sense of twelve bars. I love that guy. He is the one. He is the blues guy that got me. I bought the records and sat down and figured it out.

Can you talk about your songwriting process?

My songwriting process is subconscious in a way. I really don’t write using an instrument. Songs come to me when I am either walking or driving. The music and lyrics come to me and I work backwards from a title. I will get a great title and realize there needs to be a song.

I have a new song called “Nobody Likes a Show Off.” I heard somebody say that and thought to myself why is there not a song called that. I work backwards like I am serving the title. I drive back and forth to the desert a lot. I have a house in the Mojave Desert and I have an apartment in Santa Monica. I drive back and forth at night and song ideas just come to me like crazy. I try to memorize them so when I pull over, I can sing them into my phone. I hear the melody and I hear the rhythm. It isn’t until I pick up a guitar that I realize what key I was in when it was in my head. I play the chords that support the melody, so it is melody first.

Also, I have written instrumentals while sitting down with a guitar. I never write lyrical songs that way, ever. They always come to me in my head and I transcribe them to an instrument after they are written. It feels normal to me. I can picture Brian Wilson hearing everything in his head before he even sits down at the piano.

Can you talk about your radio show, The Many Moods of Ben Vaughn?

When I was a kid, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to be a DJ or the guy who makes the records. When I was in high-school, my voice dropped and my friends told me I had an FM DJ voice. It kept the fantasy going that I could be an FM DJ or a musician. I knew I needed to be involved in music either as a songwriter, a DJ, a performer, or a singer. The songwriting caught me big. I landed a record deal and started a recording career. I left the record business for ten years and did music for T.V. shows.

When I was done with that, I realized it was time to pursue the radio fantasy. A station in Memphis, WEVL, asked me to come and guest DJ. There was a great reaction and they offered me a weekly show Fridays during drive time. I could record it in LA and send it to them. I started doing that and it put me on the air fifteen years ago. It is all in analog and I even use eight track tapes. I make a big deal out of it when I play an eight track and make sure people hear me putting it in.

What is the trick when writing for T.V. & Film?

When I was a kid and I would watch T.V., I would pick out the instruments in the underscore. If I was watching ‘Dragnet’ or ‘The Fugitive,’ I noticed when there was a dark alley, bongos were played. Or a muted trumpet would show up during certain parts. I’ve always been able to pick out instruments on records. I would pick out the instruments all the time when I was watching T.V. or at the movies. I always thought that it would be really cool to score films. When ‘Pulp Fiction’ came out, I decided that was what I wanted to do. I was entertaining the idea of moving to LA where you have to be to get the work. You have to be available to go to the meetings in person and to the spotting and mixing sessions.

When I visited, an agent who was involved with ‘Pulp Fiction’ took me to a private screening. As soon as the Dick Dale number came on at the beginning, I realized I could get work. I have been playing surf guitar since I was a kid and it was not valued in the marketplace. It was like speaking Latin. I was dedicated to the art-form because I loved it: the reverb, tremolo picking, and using a vibrato bar. The agent who took me to the private screening told me if I moved to LA, she could get me work. I wanted a reason to write music every day, because the record industry doesn’t give you that. You may come up with twelve songs, go into the studio and record them, and tour for close to a year promoting the twelve songs. Then you go back and record another twelve. You might write twelve songs every year and a half and that’s it. I love the writing process and that wasn’t enough for me and I also wanted to be challenged to have to write in genres I had never written in before. I figured Hollywood would be the place.

When I arrived in LA, I figured I would be working on weird independent films that wouldn’t make much money. I wanted to be creatively active. That was always the engine driving me as I wanted to be learning something new, be useful, and be working. I was discovered by T.V. and next thing you know I was working on ‘3rd Rock From The Sun,’ which became a huge hit, and ‘That ’70s Show.’ I was hot for a while there. I stepped away when That ’70s Show’ went off the air. I took that as a sign, as I did it for eleven years. Near the end of the eleven years, I didn’t feel like I was learning anything new. I was repeating a lot of what I had learned. I felt it was a good time to step away and get into another less mainstream talent that I had that was put on hold because I was so busy with the demand of delivery.

Television is incredibly intense. You are on the air every Tuesday night and you can’t postpone it. You are on the air, so whatever you lay down, and marry to picture is going to be on the air whether you like what you did or not. You have to like what you did so your first choice has to be the right choice. It was exciting for me and I responded well to it. It took all of my neurosis away as a writer. If I was neurotic, I would be fired. There’s no room for neurosis.

What’s your favorite record of yours and why?

I don’t have a favorite of mine. My new one is my favorite, but that is what every artist will tell you. That is a hard question to answer.

Favorite record you produced for someone else?

As a producer, it is the Arthur Alexander record that I did for Elektra. I am so proud of the product and I have so many great memories as to how the record was made. Getting to know Arthur who was a songwriting hero of mine was incredible. He was such a subtle and graceful songwriter and singer. He was a huge threatening looking guy but then we he opened his mouth; it was like I feel your pain. I felt that guy’s pain. He was such a gentle soul.

I learned so much and I was able to work with Dan Penn AND Spooner Oldham and The American Studios Band in Memphis that backed up Elvis, B.J. Thomas and The Box Tops, and Neil Diamond. For me, it was a dream all around. Working with Reggie Young on guitar and becoming friends with him was a beautiful experience. That was the highlight of my producing career.

What is your cowriting style like and who have you written songs with?

I don’t co-write much because I am a little weird. Or so I am told. Bill Lloyd was probably my most successful cowriting partner. I met him in the 80s when he had a number one country hit. Foster and Lloyd had the number one country hit. I think it was called “Crazy Over You.” I was on tour and I met him in Austin. He came to my gig and introduced himself. Somebody told me he had a number one country hit and I didn’t believe it. He is actually more of a power Pop guy and into Big Star and The Beatles. He really loved my stuff and was paying attention to alternative music and he happened to be in a mainstream country band with the number one record. It wasn’t his natural thing. He invited me to co-write with him.

I also co-wrote with Rodney Crowell. That was a real learning experience. He is one of those guys who is so natural and so flowing. He would stop and say, “The word ‘and’ or the word ‘but’ — do we need that in there or can we just use less words?” It was an education for me on how every single word matters. He is an incredible songwriter. I have co-written here and there, but I don’t do it that much because you would have to be in the car with me.

Who has recorded your songs?

Deer Tick is a popular indie alternative band. They are pretty big. They recorded a version of “Too Sensitive for This World,” a song that I wrote back in the 80s. They were doing it onstage for a couple of years before they recorded it. I just performed with them just before the little window we had before Omicron when everything was almost o.k. They played it in LA at The Fonda Theater and they asked me to come up and play a few songs with them. We did that song and it was really great to play in front of a huge crowd who had never heard of me. It was really satisfying and it went over really well.

Marshall Crenshaw recorded “I am Sorry (But so is Brenda Lee)” back in 1985. That put me on the map as he was a major label recording artist. I may have been the first obscure songwriter that he ever covered. He came to see me play. He happened to be at a gig where I was the opening act. He recognized something in me that he responded to. He approached me about co-writing which we tried to do, but it didn’t work out. He finally just told me he was going to cover one of my songs. I liked the idea and it brought me a lot of attention. I quit my job as a landscaper when that first check came in.

Every time you write a song, release it, and get it out there, every song is like a lottery ticket that gets thrown in the bowl. You never know who is going to reach their hand in there and pull it and go wow this is the one and your fortunes change. It wasn’t a hit song but it was enough for me to actually have a career. I suddenly was taken seriously and people wanted to know who I was because Marshall Crenshaw recorded that song.

How did you meet Kenn Kweder and what records of his did you produce?

I first encountered him back in the seventies with The Secret Kids. I was at Glassboro State College which is now Rowan University. It is in the middle of the woods in New Jersey. They had a concert series and I friend of mine who went there booked everybody. I saw Tom Waits there and a whole bunch of people. One night it was Kenn Kweder and The Secret Kids and I went because I had been reading about them. David Fricke was a big fan and he had been writing about them. He was a local writer at the time in Philly and was always writing about Kenn Kweder. The band comes out onstage without a singer and all of a sudden two people were pushing a refrigerator on wheels or some kind of freezer on wheels and they pushed it out onstage. The door flew open and out comes Kweder wearing a white jump suit holding a cane. I think he was wearing a hat too. It was like ‘Clockwork Orange.’

The band was playing and he goes up to the microphone and screamed for a minute straight. It was like one scream. It went on and on. I thought to myself, this is my favorite performer. It was the best thing that I had ever seen in my life. I have never recovered. I found out later he had folk side to him and that is when we worked together. We did a cassette only release which is kind of humorous. It was called Kitchen Folk. We got together in his kitchen and he would play me songs and I would listen to them and make notes. He wanted me to produce him and I was really into it. I wanted to do it the old way where you sit around and listen to the guy’s material. I wanted to be John Hammond with Bob Dylan sitting in my kitchen. I listened to a lot of songs and we chose a bunch and went into a studio in Camden.

The whole thing is mostly acoustic and we did some electric stuff too which ended up on a double L.P. retrospective thing. I think there was a Man Overboard album too. My ability to tell you exactly what I produced is a little hard because he released it in kind of a convoluted way. He is a genius. The permission he gives himself to be Kenn Kweder is really impressive. He was an influence on me because he gave me permission to be Ben Vaughn. That wasn’t natural for me because I came from a very humble background where my parents’ idea was to never call attention to yourself.

It is pretty cool to embrace who you are and put it out there. Kenny was one of the first guys I was able to witness up close doing that. He’s a great guy and an unbelievable artist and I am so happy he is still creating and still performing.

How about Jesse Graves?

In the 70s I went into a bookstore in Philly. It may have been a junk store with books. I can’t exactly remember. I went in and he was working behind the counter or he was just there. I think he was doing some day drinking. I found a Jesse Graves record in a stack on the counter. I brought it up and asked how much it was. He gave me a really weird look. He asked me if I liked Jesse Graves and I told him I hadn’t really heard him yet but I was curious. He goes, “He’s really good.” I looked at the cover and looked at him and put it together. He ended up giving me the record and a book on Gestalt Therapy, which he told me I needed. That is my Jesse Graves story.

And I went home and listened to the record and fell in love with it. That is one of the most low-fi recordings, but I loved it. I never saw or heard of him again and maybe he left Philly around that time. He was always a mystery to me because I heard the name and ads from The Main Point or wherever he was playing at the time. I always loved the name Jesse Graves. It is a perfect name. He was already legendary in my mind. My only run in with him was as weird and mysterious as I had hoped. Then he disappeared. It was like the perfect story. He is definitely an original.

Who would you like to work with that you have yet to?

I would have say Van Morrison pre-Covid. My dream was to produce Van Morrison and then get fired midway through. That is what would happen. He wouldn’t give me as much control as I would want. I wanted to be able to tell the story as to how Van Morrison fired me. Obviously, Dylan. The one person I would love to work with but I don’t know if she is still singing is Jackie DeShannon. I am a huge fan. I think it would really be great to work with her. Most of the Blues guys that I would want to work with are no longer here. My list used to be very long.

What else do you want to accomplish?

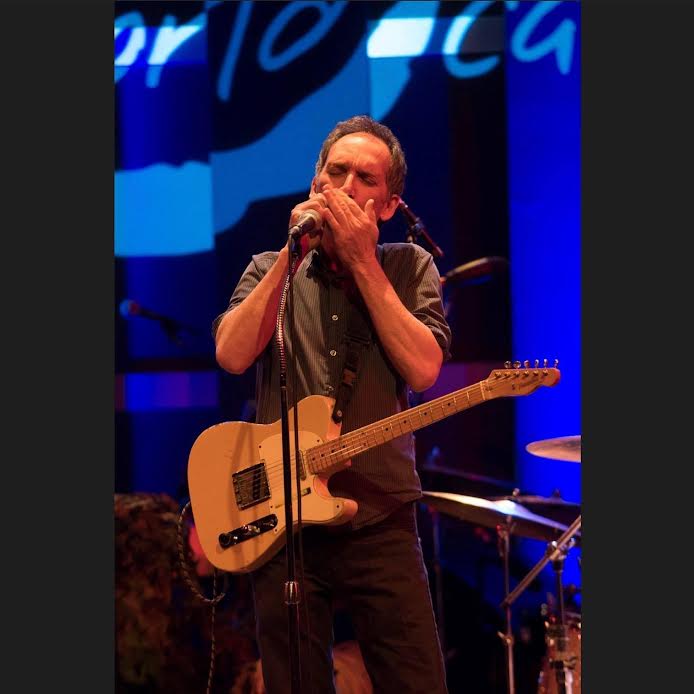

I would like to stay onstage and be vital and stay onstage a longtime. When all this madness it over, I want to hit the road and be out there. I used to tour constantly and when I quit touring and went to Hollywood, I never got back into it much. I am still popular over in Europe and I go over there and play about ten shows and that is about it. I really want to be onstage as I love communicating with people, watching the reaction, and then reacting to their reaction. I really miss the communication.

It is interesting, philosophically, to navigate what we are in. I have definitely become deeply philosophical as I have had more time to do it. The lack of activity with other people has caused it. I really appreciate music-making and people who gather in a room for the sake of enjoying, sharing, and mutually receiving music. It now seems like an exotic, beautiful thing to me. The value of it I am really starting to get.