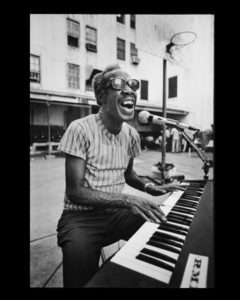

Today is the birthday of the funky, enigmatic, and wildly talented Professor Longhair, who’s outstanding life and music have touched millions for generations.

Lovingly known far and wide as the “Fess”, the godfather of New Orleans piano, Professor Longhair was born Henry Byrd on Dec 19th, 1918 in Bogalusa, Louisiana. The family moved to New Orleans shorty after his birth and, though he did get music lessons from his mother, he would say that his first musical instruments where the bottoms of his feet! As a child, he used to tap dance on street corners of the French Quarter for spare change.

Byrd didn’t get any real serious interest in music until he was in his late teens. He was a member of a dance troupe when he had to fill in for the drummer one night (no one knew he could play the drums — not even him!). Tuts Washington, the piano player in that group, told Byrd he should continue with the drums, which he did. Pretty soon he got tried of having to lug a drum set around, and switched to the piano. Tuts acted as one of Byrd’s early mentors on the piano. Fess also got encouragement from Sullivan Rock who taught him how to play the standard “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie”.

The Birth of Fess

One of Byrd’s strongest influences came from working with a government road crew. The job’s tenure was for 6 months, and involved a good amount of traveling. During these travels, he was exposed to a variety of Latin and Caribbean band music. Drawn by the rhythmic interplay of the music, Fess soon incorporated the unique syncopations into his own playing style, by blending them with blues and barrellhouse piano. This “Rumba Boogie” as he would later call it, would turn out to have an immeasurable impact on New Orleans music, and in Piano Blues music as a whole.

In 1942, Byrd was inducted into the army, and left 2 years later on a medical discharge. Afterward, he spent spend the next few years working as a cook or as a professional card player. Gambling would always be his “second profession”, as he would say, and he became well known in New Orleans as an amazing card shark. In the mean time, he would play occasional gigs as a piano player, but he wasn’t noticed as a musician until 1948, when, during another band’s break, he played a few songs on the piano at a club. He caused such a hoopla with the patrons that the owner of the club fired the band and hired Byrd, right then and there! It was at this club that he would be given his nickname, Professor Longhair, because of the ponytail he sported at the time. His accompanying band was known as the Three Hair Combo, Featuring Professor Longhair, Professor Shorthair, and Professor Nohair.

A Recording Career in 88 Keys

A recording boom was happening in New Orleans at the time, and Byrd jumped right in, recording 4 songs in 1949 for a small label. Because the session didn’t meet union regulations, the songs where never released. Byrd didn’t seem to mind, however, as he was being courted by a number of labels who had learned about the piano wizard down in New Orleans. Toward the end of 1950, he would record what where to become two of his most famous songs, “Baldhead” (which made it to #5 on the R&B charts), and “Mardi Gras in New Orleans” which would become a perennial favorite and the official unofficial theme song of Mardi Gras!

During the 1950’s Byrd continued to record, and would create his signature piece, “Tipitina”. Outside of New Orleans, Longhair wasn’t enjoying much success. One of the reasons was because he frequently changed labels and monikers, billing himself as Professor Longhair on one label, Roy Byrd, Roeland Byrd, or Robert Byrd on others. At each label, of course, he signed an exclusive recording contract — something John Lee Hooker would also do! His Band would also change names as well, using titles like The Blues Scholars, The Blues Jumpers, and even this great idea for a band name; The Shuffling Hungarians!! But no matter what name he used, or what band he had, everyone in New Orleans knew who he was, and most simply called him “Fess”!

Fess had a stroke in 1954, and was unable to play for a number of months. He would record a few sessons as a sideman in 1955, but it wasn’t until 1957 that he would record again as a leader. He recorded the locally popular “No Buts, No Maybes”, but played few shows and soon faded from the public eye.

Won’t Bow. Don’t Know How.

In 1964 he recorded “Big Chief”, which was penned by the well known songwriter Earl King. “Big Chief” was and continues to be a tribute to the magical Mardis Gras Indians, who make new elaborate and ornate suits of beads every year and parade through the streets on Mardis Gras Night with a fascinating hierarchal “indian tribe”. Fess made the song into his own with an instantly identifiable riff, telltale whistle, and backed by an all-star band, which included members of The Meters and his one-time student Mac Rebennack, better known as Dr John, on guitar! With a stunning horn arrangement and one of Fess’ most unique and memorable piano licks, the song became a New Orleans anthem. The record didn’t sell fantastically, but Fess’ spirit was lifted, and he slowly began playing at local clubs and private parties again.

In 1964 he recorded “Big Chief”, which was penned by the well known songwriter Earl King. “Big Chief” was and continues to be a tribute to the magical Mardis Gras Indians, who make new elaborate and ornate suits of beads every year and parade through the streets on Mardis Gras Night with a fascinating hierarchal “indian tribe”. Fess made the song into his own with an instantly identifiable riff, telltale whistle, and backed by an all-star band, which included members of The Meters and his one-time student Mac Rebennack, better known as Dr John, on guitar! With a stunning horn arrangement and one of Fess’ most unique and memorable piano licks, the song became a New Orleans anthem. The record didn’t sell fantastically, but Fess’ spirit was lifted, and he slowly began playing at local clubs and private parties again.

Fess’ story would have probably ended here had it not been for 2 New Orleans music aficionados, Quint Davis, and Allison Minor, who where instrumental in launching the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in the early 1970’s.

They only knew about Fess from his recordings, but where determined to find him and include him in the festival. It took them nearly a year, but they found the dynamic musician working at a record shop sweeping floors. What they found was not at all what they where hoping for. Fess was in bad shape; living in poverty, with weak knees, unable to eat, walk, or use the bathroom without help. Davis and Minor nursed Fess back to health and, still weak, the piano master somehow managed to take the stage at the 1971 festival.

Then, in a story etched in the halls of live music fame, it happened…. Before everyone’s eyes, right there on the stage, a Phoenix was reborn! Backed by bluesman Snooks Eaglin, after years of anonymity and virtual poverty, the career and life of Professor Longhair made a major turn. He gave a exhilarating performance that literally bought the rest of the festival to a stand-still! Everyone there, the musicians, the vendors, the audience, stopped and witnessed the return of Professor Longhair. Suddenly, with a single performance, Fess found himself revered by a whole new generations of fans.

Davis assumed the role of manager and Fess started rebuilding his career. He began playing local clubs and a demo tape won him a European tour with The Meters. Fess recorded several songs, but they wheren’t released until much later. Actually, the only “new” Professor Longhair album was just a collection of his recordings for Atlantic Records from 1949 and 1953, but the original disks had become prized collector’s items, and it sold well, boosting Fess’ career.

Tragedy struck in 1974, when a fire broke out and destroyed the house that was Fess’ Family home and rehearsal space. Thankfully no one was hurt, but Fess lost everything he had. The house was uninsured and he was left with nothing. As it so often does, the New Orleans music community rushed to his aid with benefit concerts, and recording session time was arranged to help him. Out of those recordings came what is widely regarded as one of the best albums of the mid 70’s; Rock and Roll Gumbo.

In 1976, Fess gained further attention when Paul McCartney hired him to play at a private party that the famous Beatle was having on the Queen Mary. Fess had no idea who Paul McCartney was, but he took the job, and the performance was recorded and released as Fess’ next album. In 1977, a venue in the New Orleans French Quarter called the 501 Club was reopened. It’s specific purpose was to give Fess a regular place to play. They renamed it “Tipitina’s”. By the end of 1978, for the first time in his life, the good professor was living comfortably from his music.

“Give Him the Graveyard, that is, if he Dies”

Junko Partner, 1972

In 1979, along with Allen Toussaint and Tuts Washington, Fess took part in a film documentary called “Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together”, and signed a contract with Chicago’s famed blues label Alligator Records. Supported by a crack team of New Orleans musicians (including Dr John, in a now rare appearance on guitar,) he recorded what many believe was the best album of his career, Crawfish Fiesta. Those who knew Fess say he was more proud of this recording then any other he did. The album, recorded at Allen Toussaint’s Sea Saint Studio and produced by Alligator founder Bruce Iglauer, earned great accolades, was critically praised, and won the Handy Award (later renamed the Blues Music Award) for Best Album of the Year from the Blues Foundation. Sadly, Fess never saw the great success of Fiesta, or even it’s release. The piano genius suffered a heart attack and died in his home on January 30, 1980 — the night before the album’s release.

In a city known worldwide for it’s lavish funerals, Fess’ was something unforgettable. In 40 degree weather — bitingly cold by New Orleans standards –hundreds of friends, loved ones, and fans waited for hours before the 10am service. The funeral procession stretched 10 blocks, and included such New Orleans legends as Allen Toussaint and Ernie K-Doe, who gave the eulogy. The Dejan’s Olympia Brass Band played and the mourners second-lined in the streets as a city said goodbye to the man who’s music was, and still by and large is, the very essence of the City of New Orleans.

Even 40 years after his triumphant return at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, the spirit of Professor Longhair still flows thru the streets of New Orleans. Professor Longhair, who along with no other except for Louis Armstrong, is a patriarch of the Crescent City Rhythms, and the Big Easy Blues. He set the standard for a long, rich line of New Orleans pianists, and changed music forever.

2 Comments

Is he still going? Amazing! I remember very well seeing him play at Antler’s in Lafayette, LA, in the early 70s. On his breaks, he just lay down on the stage for a little nap. Might have had a few too many Jack Daniels.

oops! didn’t read the whole story before I commented. Glad he ended his life with some of the recognition he deserved.