The first time I listened to Persistence of Memory by Dose Hermanos in the car I kept looking at my cell phone without thinking. My automatic reaction was that it was ringing with a different ring tone. Nope. It was The CD player. By the third listen, I was having flashbacks on the dreams I had the night before.

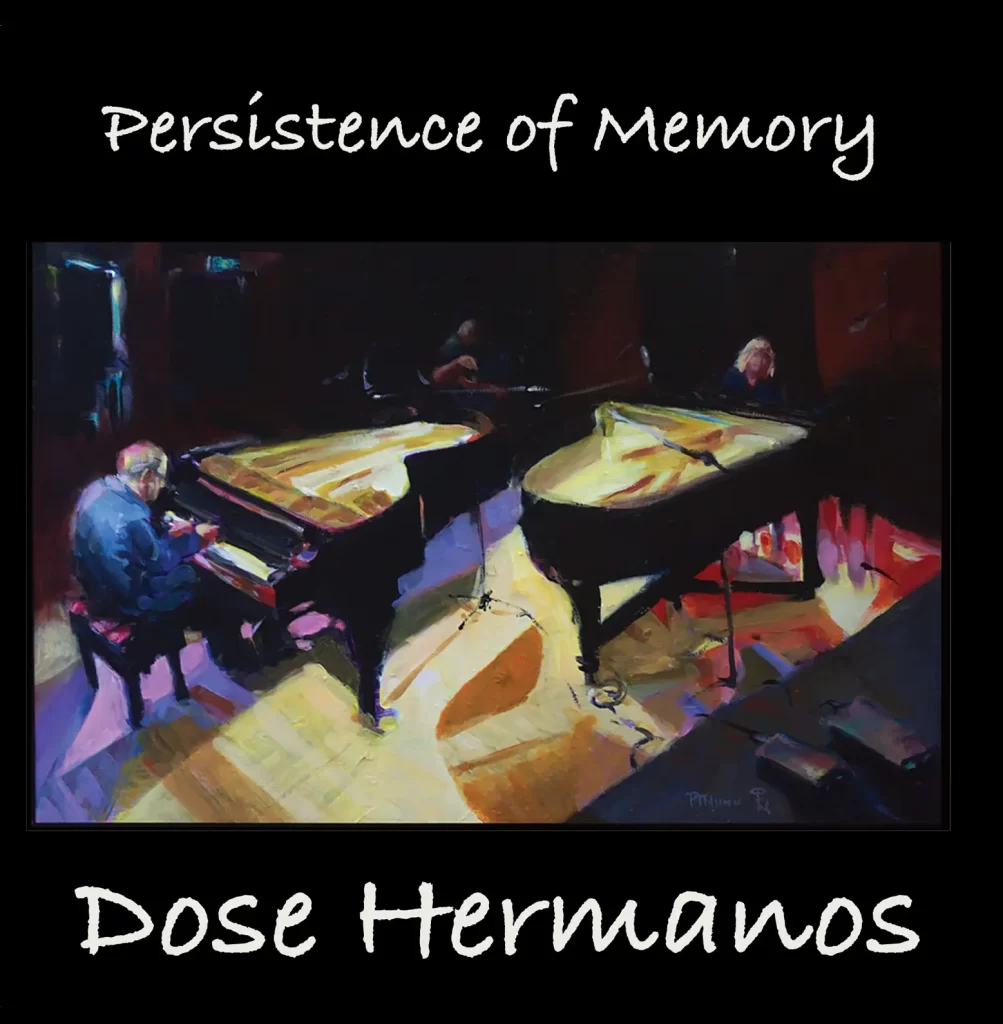

Now I’ve never taken acid, but Bob Bralove has. He and Tom Constanten are Dose Hermanos, which in Spanish means Two Brothers. And I’m guessing this album is as close to a positive acid trip as I’m ever going to get. At the very least, I have to say that my interview with Bralove was one of the most fascinating conversations with possibly the most right-brained musician I’ve ever interviewed.

I anticipated that it would be. After all, this creative genius worked with the Grateful Dead on the soundtrack to the second Twilight Zone TV series in the ’80s and programmed the synthesizers that took Stevie Wonder from point A to Z 20 years into his career.

I decided to throw away most of what I’d learned about interviewing technique in 54 years of talking to the word’s most interesting musicians and just go with my gut. So, I started our conversation by commenting that I’d just seen the 1922 version of the horror film Nosferatu the night before on a huge theater screen with a contemporary recording of the original soundtrack at 100 decibels.

“I got into Nosferatu with Jerry (Garcia),” Bralove responded.

Really?!

“Yes. He was in a collapse. We cancelled a tour. I sat in a studio at his place. What he wanted to do was score silent films.”

How wild that would have been for The Grateful Dead to score the scariest silent film ever made. Did they do it?

“We started, and then I think because he had been sick, he found the whole thing too depressing.”

I knew from the get-go that this was not going to be your father’s Oldsmobile type of interview. Now about Twilight Zone.

“I remember sampling Bobby (Weir’s) guitar. He was on headphones. We were listening back, and I’d say to Bobby just randomly, ‘Play the first view of the coffin,’ and he would respond to that. ‘Now play the magic symbol that’s just been shown to you (in the film) and then these little phrases.’ He would play these phrases. We recorded that, and we’d take ones that seemed to be in a good part of the show and lay them in.

“Mickey (Hart) was doing the sound design: the footsteps and the knock on the door, that kind of thing. It was more musical than I really experienced sound design to be. We would have pitch bent Tibetan prayer bowls to create an energy. Sometimes music was layered on that. If Merl (Saunders) and Mickey decided to take the same cue, they would be combined in L.A. for the mixing session, and sometimes they would be left alone.

“It was a great show. Twilight Zone had complete energy. The whole idea of an anthology show was kind of new when I saw it. The most that changed every night was a variety show or something like that. You had the same cowboys, the same – you know.”

Bralove and Mickey grew particularly close during the Twilight Zone sessions. One particular memory that influenced Bralove’s work on Persistence of Memory involved performing with 10 Buddhist monks chanting on stage at the Shoreline Theater in Mountain View, California.

“Mickey said, ‘I’m gonna go on the I beam, and you just keep on going. I can keep on droning.’ I would actually blast the monitor speakers into the strings of the beat and keep them vibrating. So, I could drone the I beam as long as I needed to.”

The I beam is the large device that Mickey banged and played with a steel pipe.

“It’s below that the steel pipe with the oversized piano string. It goes down to 16 cycles. So, that thing that was the sound of the napalm in Apocalypse Now is a musical instrument. It’s actually an I beam with these strings, and I would tune it in octaves and fifths and you could delicately play harmonics or smash it with a pipe. Mickey would dance through all of it. He says, ‘Ok, when I get off the stage, you keep that going. I’m gonna go get the Tibetan monks, bring them on stage and let them chant.’

“When they got going, they were chanting three tones at the same time. So, there are 30 notes going on, right? And he says, “When I tap you on the shoulder, you play out of the monks and the visible sound check. I got some tone clusters I thought would cross fade the monks.

So, Mickey gets off the drum riser and gets the monks. When the monks started, I pulled down the faders on the I beam.

“I’m standing here, and I think pretty much this is the sound of God. I mean you know it’s religious masters chanting three notes at once, 10 of them going through the greatest sound system in the world in volumes that are rolling your socks up and down, and I have to follow it with a Japanese synthesizer. So, I start chanting with them, and all of a sudden a chord came out.”

In 1996, after Jerry died, Dose Hermanos went on their first tour of the United States. “I grabbed the microphone, leaned over Tom and said, ‘Just follow me.’ We were very high on LSD at the time, and I grabbed the microphone and started chanting. It turned into this marvelous piece which just played amazingly around what I was doing. Just fantastic, almost doing gymnastics musically around this thick tone. At the end of the performances there was a moment of silence. (I thought) Oh, you really blew it, Bob. And the crowd just cheered. It took a moment to process.”

Bob worked with Stevie Wonder in 1980. “Stevie wanted me to make synthesizers talk to him so he could program them. One day he said, ‘Maybe you want to stay for a session I’m gonna record. You might want to see how it goes.’ He was doing an overdub on a new track, and he played a Yamaha CS80 with a rhythm controller. He had an old Yamaha synthesizer that had a rhythm controller that could bend the notes instead of a pitch control you see on some synthesizers today. So, you’d play a note and grab this strip along the keyboard and bend the notes, and he was rockin’ in the overdubs. He was just in the isolation room, and he was just tearing it up on this keyboard.

“I was almost at the end of a master’s degree in composition, and I said to myself, ‘Oh, my God. This is the first music lesson I’ve ever had.’ It was just life pouring out of him like he was just effervescent and filling the room, and I thought, ‘Ok, this is what I had been looking for. It doesn’t really matter what you’re playing. If you’re generating this, you’re doing the job. This is the energy. This is what it’s all about. It isn’t all about scratching note on paper. It’s about that communication of joy that music really is.’”

Persistence of Memory is not meant to be described in words. It needs to be experienced as a connection between the lower chakra and your brain. “For me there are a lot of different approaches to creating music, and I think they’re all valid, and there’s something about the Dose Hermanos thing that needs to be the right connection, not one that has to go through the mind. You need to illustrate those connections. If the connection isn’t happening, if it isn’t framing, you aren’t in that zone which is a very special zone for Dose Hermanos.”

“Tom and I are both keyboard players. We have references within The Grateful Dead perspective and outside the Grateful Dead perspective, and if that isn’t all jumbling and flowing and unencumbered, it isn’t us. And sometimes it’s different. And it feels like it flows that way. You realize, ok, that’s going to make another record. You don’t have to think about it. You know what I mean? If you feel it – the thing is when Tom and I are going over material for a record, there’s very little disagreement. It’s just really direct.

“If you want to know what the references are, they’re a bit erudite, but the connection isn’t. We’re using those references like a classical piece or something like that. It’s not to imitate but to create something original that says, ‘Oh, I like that so much I’m going to do one of those.’ It’s not exclusively the lower chakra. If the lower chakras are not connected, it’s not us.

“It’s difficult to talk about because the structures themselves are improvised. It isn’t four bars of this and eight bars of that, and move back and return to the chorus, the structure itself.”

When Dose Hermanos performs “Garden of Delights” from the album in a concert, it’s never the same way twice. “It becomes copyrighted at that performance. We come back to the same textures. It opens with those piano notes, and then the strings respond. So, that conversation is a textural thing that is our performance. And the truth is not because everyone is different. It’s hard to imagine someone else saying, ‘Ok, I’m going to do that song ’cause which one is it?’”

Chances are there will never be a Dose Hermanos cover band. “Yeah, exactly. And if they do any of our tunes, I’ll be thrilled. “Midnight Train to Bangladesh” could be done I suppose. That’s from an old album.”

“Cocktails for Darlene” maybe?

“Maybe. I’m not worried about it.”