Like Detroit’s Motown, Stax Records in Memphis was a family. While Motown was smooth, Stax was gritty. And being a bi-racial label in the south presented challenges.

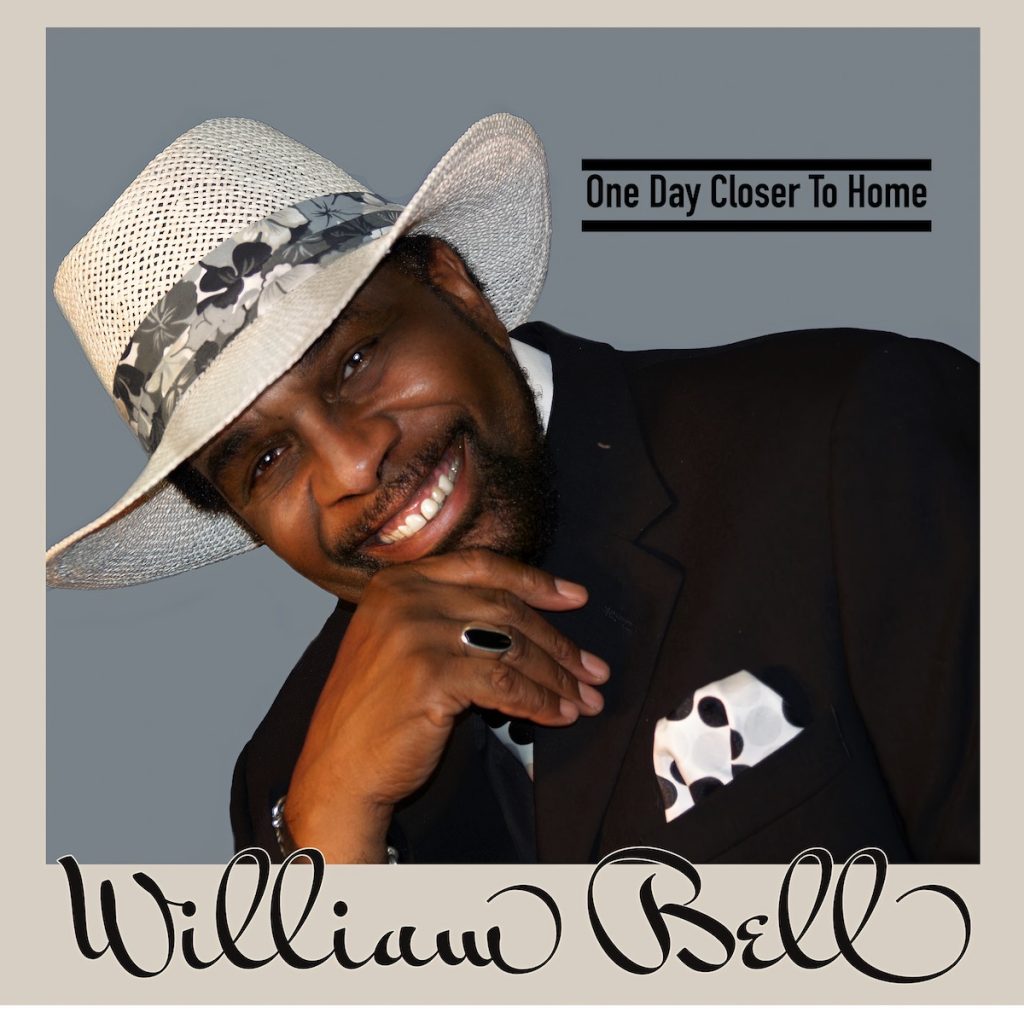

William Bell was there in 1961. He wrote “Born Under A Bad Sign” with Booker T. Jones at Stax, who told The New York Times in 2016: “He was an innovator as a singer. He set the standard for Percy Sledge and all who sang with heart, soul, and feeling.” His “You Don’t Miss Your Water,” a 1961 Stax hit and one of the quintessential soul records to emerge from the Memphis scene. At 83, he has just released his 15th Studio Album One Day Closer To Home on Wilbe Records.

“We were like family inside the confines of Stax. When we came out, we caught flak, but inside we didn’t care which race or religion or what sexual thing you were. We just wanted you to be creative and have some (licks) that we could exploited, yeah!

“I worked at a club on Hernando called The Flamingo Room, and Elvis used to come by there. He would visit the churches and come by the Flamingo Room to watch us perform and everything. So we all knew each other.

“Sam Philips, at Sun Records in Memphis was a forerunner, and then Jim Stewart at Stax followed up on that. People like Rufus Thomas were also on Sun Records for a while, and we were all kind of a small, but a tight knit unit of people from the same neighborhood. I was from South Memphis. Rufus was also from South Memphis. He was a deejay on the only black station, the first ever, WDIA. So we all knew each other and had families and such. So it just worked out great.

“Of course, it was during the times of staunch segregation, but we didn’t care. We just moved along inside the confines of the music buildings and everything. We just got along great, and it was that way for everybody, the rockabilly players and the blues singers, because we heard everything on the radio. I heard country, gospel, blues and jazz and all on the same stations during the day.

“But you know, you learn to adapt, and you realized we were all working together, and I was fortunate enough to start at an early age. We were just totally melded together from clerical people to the musicians, singers, everybody, and we didn’t care. We didn’t even look at color inside those confines.

“We were just really grass roots. Most of the artists came right out of church and into secular music, just like Sam Cooke did. We realized that the same people that worked hard all week, went to the clubs on Saturday night and went to church on Sunday mornings.

“Those same people bought our music. It was like the grass roots level of feeling that we projected, because it was all stemming from the church. We laid the blues stuff we’d heard from the masters like B.B King, Bobby Bland and Jr. Parker, and all of those guys, and also Ike and Tina Turner. So it just melted all together. We didn’t realize that we were creating anything. We just did what we felt was natural, things we had been exposed to all of our lives.”

“When I started working with Rufus Thomas, I was 14. like I said, he was a deejay on WDIA, but there was a theater on Beale Street that was about a block around the corner from the club where I worked, called Palace Theather. They had a Wednesday talent contest and working at the club Flamingo, I had a doo wop group called the Del Rios.

“So, we would work at the club and during the intermission I would always run around to the theater, because everybody knew me, they would let me in. The stage manager wrapped me up in a stage curtain because they had what they called shake dancers at that time that were scantily clad women and I was too young to be there.

“Rufus Thomas was the M.C. and he had a guy with him called Bones, and they performed as Rufus and Bones. He was also an M.C. and comedian, and they would do a little dance, singing and comedy skit like Pigmeat Markum and Baby Seals.

“They would always let me in, and I could watch the show and wrapped up in the stage curtain. Rufus and I got to know each other. I knew his son Marvel and his daughter Carla. My group did the backup recording on ‘Gee Wiz’ for Carla Thomas.

“When we went out as the Stax Review in the States, we had a mixed group with the Mgs as rhythm section and the horn section with Wayne and Andrew, members of the Memphis Horns. We were all black and white together, and we would travel in one bus most of the time. The horns and the band, and maybe two or three artists.

“Sometimes we’d stop at a restaurant and they wouldn’t serve us, we had to go around the back and categorically, every artist, Steve Cropper, Duck Dunn, Al Jackson & Booker T. and to their credit the white musicians all said: ‘Well, if they can’t eat here, we all won’t eat here either!’ We all left out and would go somewhere else. The same thing happened at the clubs and venues where we worked.

“Sometimes black clubs would be hostile to white musicians and everything and we would say, ‘Hey, man, chill out, you gotta come through us to get to them, you know we’re family!’ So, they would, but sometimes vice versa. We had to have two different sets, one for the early sets in the afternoon for the blacks, and then later at eight o’clock at night, for the whites. When we finally started playing on tours we stopped it. We were going to do one set, one show for everybody! So, the venues would put the blacks upstairs and the whites downstairs, still segregated, but it was a start.

“It made a difference. A lot of times we caught flak but we ploughed along. We’d see crosses burning sometimes in the south. So it was a lot of stuff that we went through as a unit, that would completely come together as a mobile family at Stax. We just never really got into the color thing or the prejudicial thing, like Steve said, we didn’t care. But when we come out of Stax sometimes, the police would sit outside and wait until we came out, try to harass us and tailgate us all the way home and stuff like that.

“I feel myself being very fortunate not only for having my health and strengths and I tell people all the time ‘I can still scratch my own itch!’ I feel very fortunate to have good health and my good frame of mind. Coming out of the projects with David Porter, Maurice White from Earth, Wind and Fire, we were all neighbors from across the street.

“We all came out of the same area, and about six blocks from where the Stax building was, at South McLemore. So, I feel very humble. I’ve performed for three Presidents. Two in The United States, President Bush Sr. and President Obama and then one in Africa, President Tubman, and I’m still standing. The man upstairs is very kind to me.

“At one time in my career we traveled for 90 days at a time in buses and cars, playing one nighters. To travel that long and still be healthy and not have any injury or something, it’s amazing. I’m amazed at it ’cause I think of some of the things we did and nights we traveled all night up and down the highways, sometimes two-lane highways in the fog.”

Editor’s note: This is part one of our feature on William Bell, read part two here.