Gone!

His apartment obliterated.

His car? Under water.

Perhaps most unsettling was the guitars Katrina destroyed. “All my guitars except one, and it was the cheapest guitar I had. It was in a plastic case that apparently floated. That one managed to be salvaged, and I still have it. But other than that, I lost a Les Paul, a custom shop Strat, and all the master recordings of everything I’d done at that point was gone.

“I happened to be out of town that weekend. I didn’t evacuate. I was watching it from afar, and so on a certain level, at first, you’re just thankful. It’s hard to feel sorry for yourself about losing things when you’re seeing people literally suffering. So, I counted myself really fortunate, and at the same time there was a lot of reckoning that I had to do.”

Music just may have saved Eric Johanson’s sanity, but at first there was a little detour involved. He moved from New Orleans halfway around the world to New Zealand for four years.

“People say, ‘Well, why did you do something as big as move out of the country?’ And all I can really say is to wake up and realize you only have the suitcase that is with you, and everything else that you ever had is gone. I had just gotten out of college with a degree in philosophy. I never intended to do anything with it, really. I mean I had notions that I would maybe continue on with a postgraduate program or something like that, but not ever really with the idea that I was going to do that for a living.

“Music was already my thing, and it was my thing all the way through college. I just had the ability to go through college tuition free in Louisiana, so I did. But you know basically I had to come up with something to work towards, something to look forward to moving back to a city that was still cleaning up.

“You know, saving up to do that was depressing. It felt like working toward being where you used to be was a hard thing to do. So, working toward moving somewhere else gave me a goal, a lot of hope to work toward. And it’s a beautiful place. I love it and have a really special place in my heart for New Zealand.

“I mean it’s a very peaceful country, a beautiful country with all sorts of natural phenomena, everything from beaches to glaciers and mountains. It’s just everything. It’s very clean and green and peaceful; and it was also possible to emigrate because they have immigration policies that are favorable to young people trying to move over there. So, I was able to go over there and spend some time.

“All of that seems so long ago now, but it gave me a chance to existentially blow off some steam. It’s hard to figure out a way to really describe it, but I needed to know that I could leave and go as far as I wanted to go away from anything I wanted to get away from in order to figure out where I wanted to be, and the music ended up bringing me back to New Orleans.”

Johanson lived in New Zealand for four years and resettled in New Orleans during the 2010s. He became a session musician for artists including Cyril Neville, Anders Osborne, and the Neville Brothers and has worked with JJ Grey, Eric Lindell, the Neville Brothers and Tab Benoit. His four most recent solo releases have all gone top-ten on the Billboard blues charts.

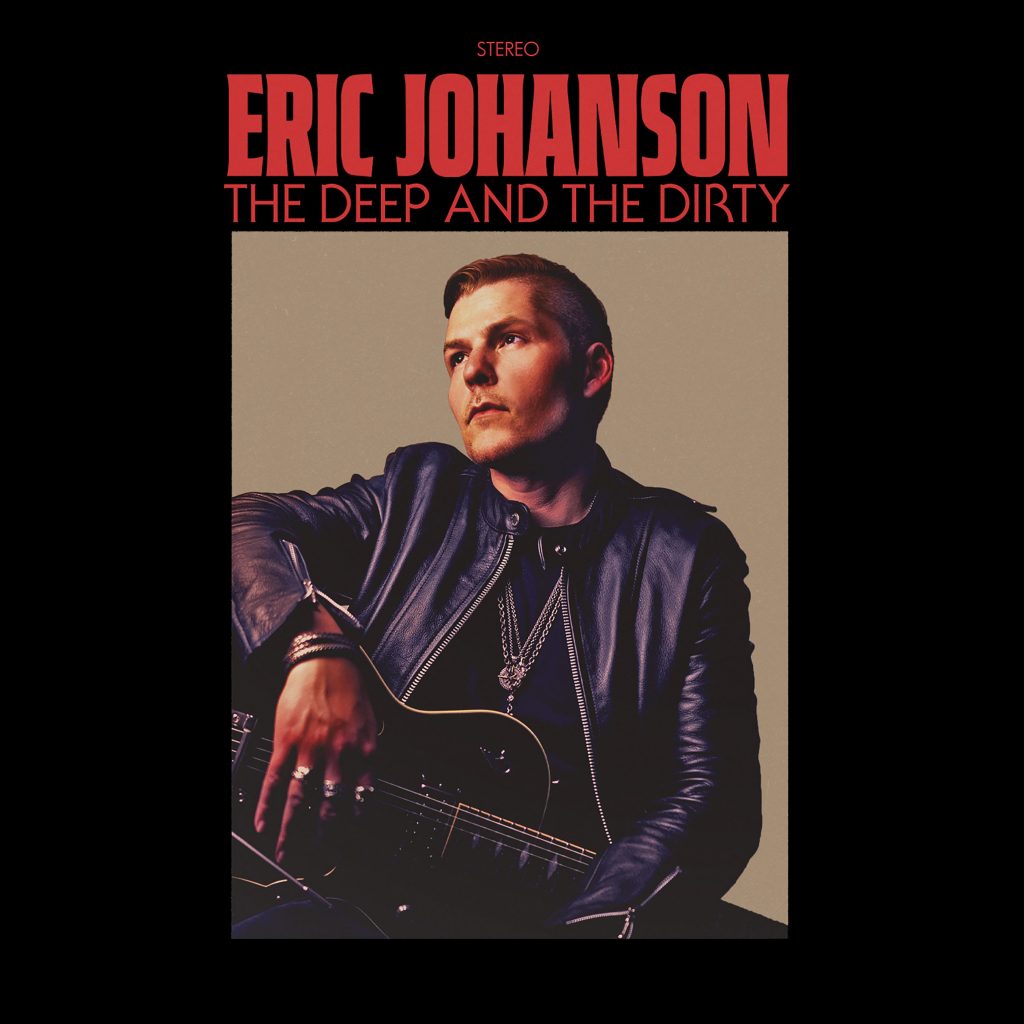

His new album The Deep and The Dirty drops July 28th on Ruf Records. It could easily be a collaboration between R. L. Burnside and Marc Bolan’s T-. Rex. Johanson is a bit intimidating in the same way that R.L. Burnside was with lines like: “From the deep and the dirty/Where the nights get blurry/ I’m a southern thunderstorm/Baby don’t you worry/I can treat you right tonight/And be gone in a hurry.”

There’s also a sense of rock and roll abandonment that T. Rex formulated in the 1960s that gave heavy metal permission to color outside the lines. “Produced by Jesse Dayton (Supersuckers, Rob Zombie), it was recorded in the studio as a band playing together live with bassist Eric Vogel (Big Sam’s Funky Nation / Fred Wesley) and Grammy-winning drummer Terence Higgins (Ani DiFranco/Warren Haynes/Tab Benoit).

“I think I’m as interested in sound as I am in songs, if I’m honest. The things that excited me when I was a kid, hearing things that made me say ‘I wanna play guitar.’ I wanted to do that. It was the sound of it. It wasn’t, ‘Oh, this song is about this thing. That makes me think about the other thing that happened once.’ It was the raw, visceral, in-the-moment experience of the sound itself.

“I think the deadlines and the time crunch helps to clear away a lot of distractions and overthinking. People ask me, ‘You must have been writing a lot of stuff during the pandemic.’ To be honest I didn’t find it easy to write a lot of the time. I was sort of trying to keep involved in different ways, but it was sort of like how do you even know what you’re reflecting on when it’s happening currently.

“So, when there’s a deadline going into the studio It’s like all of a sudden, I can focus. A lot of these songs were written two weeks before going into the studio, but I had gone back and forth with the producer singing some different songs, but they were right before I went into the studio. Like the week before we were supposed to (record), I wrote a few more. I was like ‘Check these out.’ There’s something about things coming into focus as you get closer to the date of recording. All of a sudden you know what it is that you need to do.

“My first experience in rock music was MTV, and then seeing arena shows like Metallica, so that was my first ‘Oh, my God. I’ve gotta do this with my life,’ but that translated into the sound of early blues. It’s always been the texture and the sound that really draws me in. So, I think that as a result, for me I’m naturally going to head toward a certain excitement level with what I’m doing. I’m not interested or able to try and sound retro or old-timey.”

He plays a steel resonator guitar on “Just Like New,” enthusing, “It’s such a beautiful sound and to me that’s a part of what I do as well. In some sense playing a guitar that is made in the same way as it was in the ’30s and playing it with the same just bare hands that would have been played in the ’60s to some extent might sound old or whatever, but I’m not intentionally trying to make it sound old.

“My main one is a National. It’s actually a 2013, but I mean they’re made in much the same way as they were at that time (the ’30s). That’s the one I came across, and I’ve come across some old ones that are hit or miss depending on whether they really sing, or they sort of have a lot of work that needs to be done. So, I’m perfectly happy with the newer ones.”

I told Johanson that everyone always tells me their new release is their best yet. Does he think The Deep and Dirty is his best?

“It is, and I think there’s not a song on it that I don’t look forward to playing live. I think as my sort of journey as a songwriter and artist there has always been a part of me that has wanted to experiment more with the writing and the different riffs and the different tonalities, and then at the same time there’s a part of me that doesn’t want to stray so far from the roots. They become cerebral or rewritten because I’m trying to leave that space and improvise in the moment.

“I think that with this record I feel like it’s not trying to stick to a certain format or genre. I feel like it’s getting more in a natural place to me where the songwriting and also the improvisations and the rawness where they’re arriving at a more natural place, and I feel like that’s happened a little bit more on each record from me because I’m not specifically trying to stay in a particular box, but I am trying to make sure the human element, and the feel is still the driving force there, you know. The inspiration is the driving force and not sticking to a template. So, yeah, I think it is my best record so far, and I’m really looking forward to getting out there and playing.

A personal note: I try to write every article to a specific receiver. This article is for JD Nash. Rest in peace, brother.