Founder Chris Strachwitz captured vernacular music for posterity. He was an Army veteran with no education in how to record music. His one-man operation produced more than 400 albums during more than 40 years in operation, exploring the far corners of American vernacular music – blues, gospel, Cajun, zydeco, bluegrass, Texas-Mexican norteno music, and more.

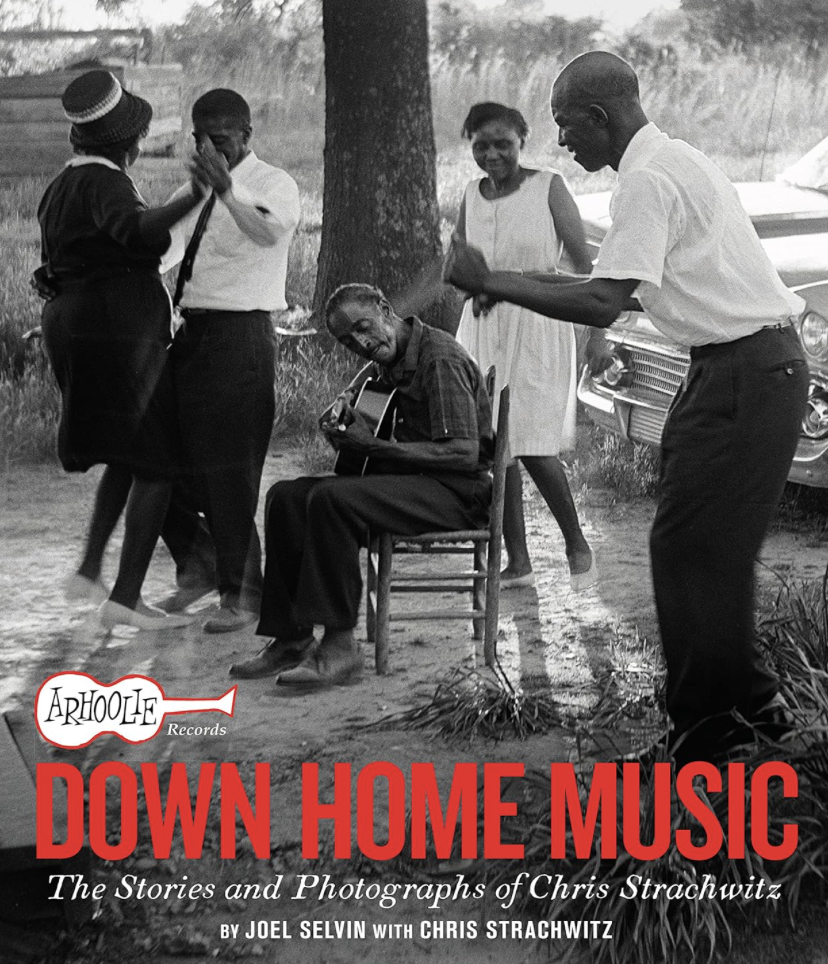

He documented more than half a century of his efforts capturing images of the artists he recorded like a butterfly on the wing. It’s all captured in a book just released called Down Home Music – The Stories and Photographs of Chris Strachwitz.

Joel Selvin, author of 20 books on music and a veteran music journalist for the San Francisco Chronicle, supplies the back stories to more than 200 pages of Chris Strachwitz’s photographs that jump off the pages. This larger-than-life coffee table book begs you to listen to the music of Lightnin’ Hopkins, Clifton Chenier, Sonny Boy Williamson, Flaco Jimenez, Big Mama Thornton and scores of others who pour out their rich and disparate cultures. Down Home Music is first-rate proof that America’s musical heritage is our gift to world culture with a capital C.

“The Strachwitz book is so much a piece of my heart,” says Selvin, a half-century friend who was there for many of the Arhoolie producer’s recording sessions. “I was going over there two or three times a week. It was just gorgeous. It was like a golden opportunity to drink in this friendship at the end of his life. Every lunch, every outing was a postgraduate seminar. He was just so much fun and we did so many things together.

“So, yeah, I saw him record in his house. I saw him in the studio. I saw him do live recordings. I tell you, I used to go out to this Catholic Church gymnasium in Richmond – and Richmond is really funky shit, dude. People lived in East Bay their whole life without going to Richmond, and they had these things called French dances there because the congregation had a lot of people from Louisiana.

“Clifton Chenier would play these four-hour sets followed by a brief break. Then, he’d come back for one last one-hour set with a crown on his head. Chris did a live album there called Live at St. Mark’s Hall, and I consider that one of the finest albums, period! Paragraph! Ever! And those nights at St. Marks’ Hall are absolutely without question some of the finest music experiences of my life.

“I want to tell ya. There were not a lot of white people there. It was a pretty obscure little arcade dance. Chris would do the like rock clubs. He’d come to town and do San Francisco’s Berkeley rock clubs, and then he’d do one of the French dances.

Chris Strachwitz died shortly before the book was printed.

“He was 91 years old, but it never crossed my mind that he would die. His passing was out of the question, Here I am talking about him, but you should be talking to him.”

Smithsonian Folkways, who has picked up the mantle of the Arhoolie catalog, credits it with being the most important record label of the last 60 years. “In 2016 (Arhoolie) sold the label to Smithsonian Institute. Suddenly there wasn’t a record company, and it became incumbent upon the people there to do other things, and they have this Arhoolie Foundation that Chris established.

“They transferred all the titles of Chris’s stuff to the Arhoolie Foundation, and his longtime partners Tom Diamant supervised the digitization scanning of all of Chris’s photo library. And keep in mind Chris had a camera when he was in the Army in 1952, and everywhere he went, he took a camera with him. So, the first night he saw Lightnin’ Hopkins in Texas he had a camera.”

“The only competition was Rounder,” says Selvin, “and I think those guys would take their hat off to Chris. He showed them the way. Chris recorded all those guys before they did. Chris was the guy who found everybody. He found Lightnin’ Hopkins! He found Clifton Chenier. He found Fred McDowell. He found Del McCoury.

“He even had his fingers on that sacred steel shit. In the ’90s that was one of the last regional discoveries, wasn’t it? I don’t know if there’s anybody in Chris’s lifetime whose work in the folklife field comes even close to what Chris did – and without any training, without any academic description, without even knowing how to work the gear. He had to learn how to work the gear, and he did it entirely on his own, his own intellect and curiosity to drive him. You look back. He attacked the whole world of vernacular music and plumbed it for everything he wanted.”

One of Chris’s photos is of Sonny Boy Williamson fronting the King Biscuit Boys in Helena, Arkansas in 1965. A cropped version of it has appeared on King Biscuit Blues Festival publicity since the start of the festival in 1986.

“Chris was a family guy,” explains Selvin, “and in Chris’s mind these were strictly utilitarian album covers, publicity photos. The best example of that is the Sonny Boy Williamson photo. I’d never seen it before, and the whole frame is a walk through history. It’s just gorgeous.

“That’s Chris. ‘Oh, I’m not a photographer. I was taking album cover photos.’ Right! So, at some point, they had these things all scanned, 17,000 images, and it occurred to somebody that there’s a book in this, and I’m not really sure of the details in this. Chris called me, and I believe the call was actually to solicit some advice because he was thinking of publishing, and he had a design in mind. And I’ll tell ya, I just hijacked the project right there on the phone call.

“He had no interest in all the stuff mainstream media would touch. Pop music was garbage and had no meaning. It had no connection to a culture. It had no relevance. So, that was what he was looking for, and the other thing he was looking for was authenticity. He wanted to connect with the performers and their life and wanted to feel that life in the music. That’s why Lightnin’ Hopkins was the ultimate figure in Chris’s human universe because Lightnin’ Hopkins is all in. His music is what’s on his mind at that moment remarkably at that point.

“We got the book deal really quick, and for Chris to collaborate with somebody was way outside his safety zone. He was in control of everything he ever did. I think the idea of having a publishing company like Chronicle Books appealed to him a little although he was trepidatious and wary right up until the end.

“He saw the pages, by the way, and he had a sort of tentative approval. He was like, ‘This is going to be ok,’ but he was worried about printing. He wasn’t sure if he could get the registration right. He didn’t think they could print photos across two pages. He was so fussy. So, when the books actually came from the publisher, and I opened up the package, and I saw how beautifully they were produced, that was when grief hit me. I was just consumed with grief when I opened the book.

“He had died in May, and we saw the book in July, but he’d seen the pages.”

In a 2011 interview Chris explained to me his passion.“I just became addicted to various American vernacular musics and just found it a most amazing experience like some people like to go on safaris or go to the North Pole and climb the highest mountain. I just love the whole adventure of going to Texas and meeting this whole part of Americana (that) I had never any idea existed: New Orleans, Memphis, Mississippi, Appalachia, and God knows where else. That was to me the great adventure of coming to this country, these unbelievable ethnic groups of all colors and creeds. They all have their shit-kicking music. They kicked ass. They weren’t this wimpy shit in Europe. Ha, ha.”