The Folk Americana Roots Hall of Fame (FARHOF) was launched in 2019 as an initiative of Boston’s Boch Center. Its purpose is to “celebrate the lifeblood of America’s musical and cultural heritage.” In September, FARHOF announced its inaugural class of inductees, a group that included not only musicians past and present but non-performers as well. The first induction ceremonies will take place in April although an exact date has not yet been announced.

The Non-Performers category includes supporting musicians, songwriters, managers, publishers, historians, producers, and other who have contributed to the lasting legacy of folk, Americana, and roots music. Albert Grossman, Betsy Siggins, and George Wein comprise the first group of non-performers to be inducted.

Albert Grossman

Known to many as “The Baron of Bearsville,” Albert Grossman was born in Chicago in 1926. His love of music led him to establish the Gate of Horn in 1957 in his native city. It was one of the first folk music clubs in America. His ability to recognize talent led him to become a music manager with Odetta, Joan Baez, and Bob Gibson.

After moving to New York, Grossman was instrumental in forming the trio of Peter, Paul, and Mary, whose sound emphasized individual vocal personalities, a departure from the traditional folk sound of the times. He also guided the careers of Richie Havens, Gordon Lightfoot, Ian and Sylvia, Paul Butterfield, and the Jim Kweskin Jug Band among others. Bob Dylan arguably was his best-known and most successful client.

Grossman moved to Bearsville, NY, near Woodstock in 1963. His dream of creating an artist community was realized with the opening of Bearsville Studios in 1969 and the Bearsville Records label in 1970. An acoustically perfect Bearsville Theater was planned as the crown jewel of the community. Unfortunately, the theater was not completed prior to his death due to a sudden heart attack while flying to London aboard the Concorde in 1986.

Albert Grossman is buried on the property of the Bearsville Theater, which opened three years after his death.

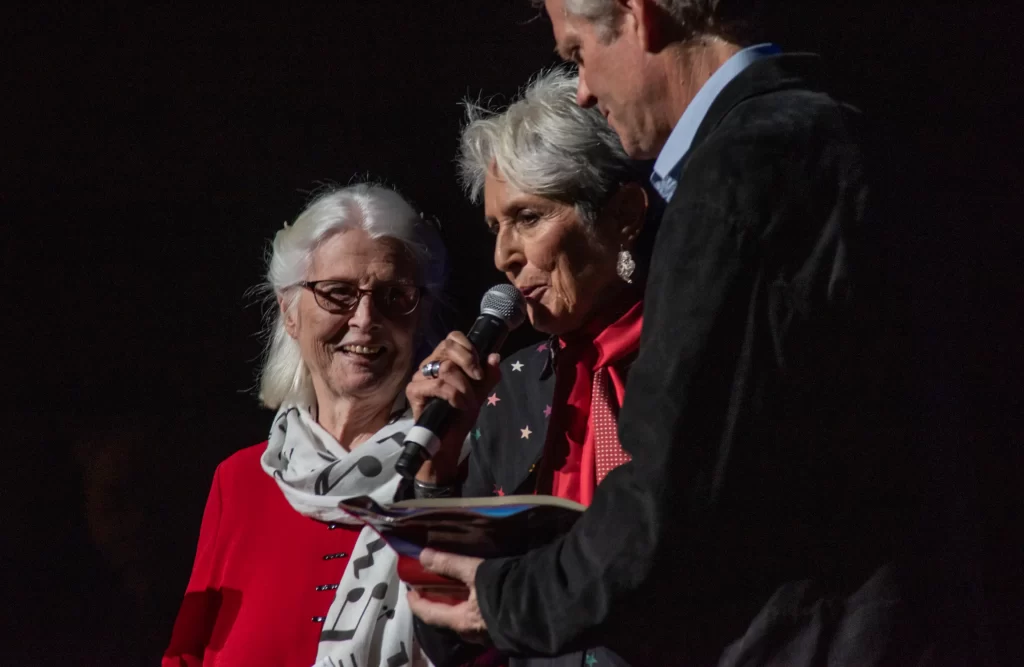

Betsy Siggins

Everyone has a key turning point in his or her life and for Betsy Siggins the turning point came in the fall of 1958 when she entered Boston University. She met Joan Baez there, an event that she would later describe as “both the best thing that happened to me and the worst thing that happened to me…” She and Baez have remained lifelong friends so one imagines the “worst” can’t be all that bad.

Siggins, along with Baez, happened upon the local coffeehouse scene as a college freshman in 1958 and she has been a central figure in the Cambridge folk music community ever since. Siggins was a founding member of Club 47 in Cambridge, the legendary venue where Baez, Jim Kweskin, and others launched the folk revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Her contributions to society go beyond the music, however. Siggins went to New York City after Club 47 closed. During 20 years in New York City, she founded programs for homeless people with AIDS and worked at various soup kitchens and food pantries, and also earned a B.S. degree in community development, focusing on women in poverty. Siggins was one of the first people to engage musicians in benefit concerts, connecting social problems requiring money and awareness with artists who shared her concerns.

Betsy Siggins assisted in the creation of the Festival of American Folklife and is a founder of the New England Folk Music Archives/Folk New England.

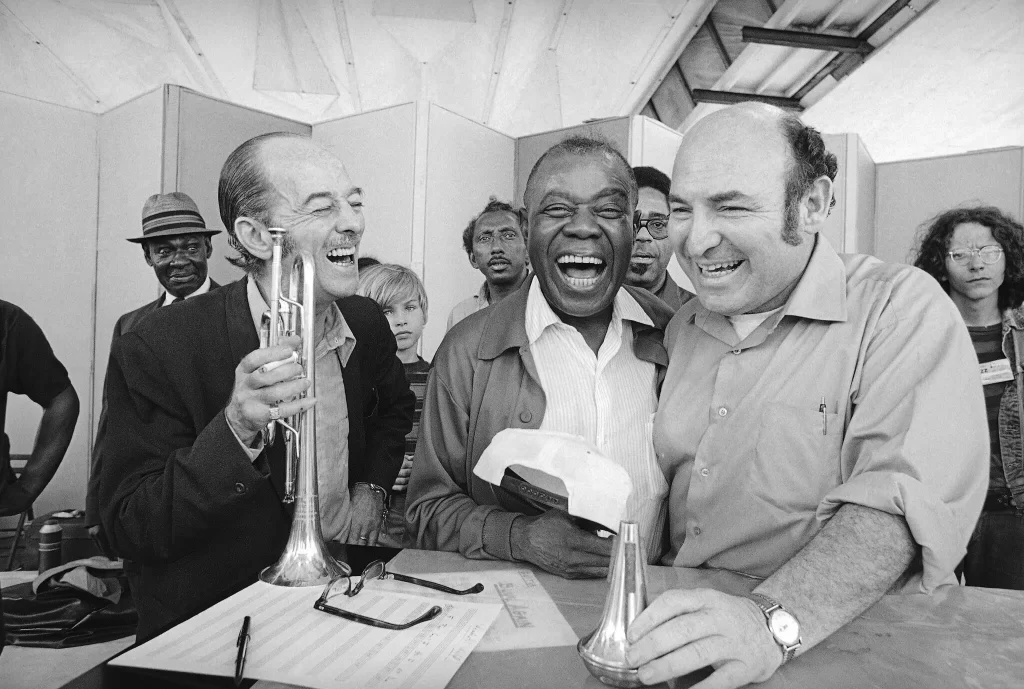

George Wein

“My real talent was making things happen,” George Wein once said. The declaration is a bit of an understatement. Some of the things he made happen include both the Newport Jazz Festival and the Newport Folk Festival. He started a production company and in New Orleans he boosted the city’s Jazz and Heritage Festival. He eventually exported his model around the world.

Wein’s model for music festival’s involved corporate sponsorship, a concept he pioneered. Schlitz Beer, Mellon Bank, Kool cigarettes, Verizon, and Ben & Jerry’s were some of the corporations willing to champion festivals.

He tried to retire in 2007 at the age of 80 but when the Newport festivals he created were on the verge of going under, he set up a non-profit foundation to protect the Newport festival’s future. “The only chance we have of keeping the festival alive after I’m gone,” he said, “is to have a foundation and people that want to keep it alive.”

Wein was himself a musician learning how to play the piano when he was eight. He developed a love for jazz that led him to meet many black musicians. It was this association that would crystallize into a concern for civil rights and, eventually, leading to the $1 million gift to Boston University. It was said he truly wanted African American studies at the University to grow and flourish with as much independence as possible.

George Wein passed away in his sleep on the morning of September 13, 2021 at the age of 95.