Bobby Rush has won his third Grammy at age 90.

“Success to me was being able to do what I wanted to do for the love of it. So, after I’ve done it now, people want to pay me for some things I thought I never could get paid for. I never thought that that would come financially for me at this time.”

After John Lee Hooker won one of his five Grammys, he came to Bobby backstage in San Francisco crying. “It was good day for me,” says Bobby, “because I was happy for him winning, and he could make a lot of money for 15 minutes a night, but he was crying because it was late.

“For me (winning the third Grammy) was better late than never. I thought it was good. John never thought he would make money. I think at that time he was making $20 to $30,000 a night. That’s good money. He thought it was bad because they waited this long to put him in position to give him the opportunity to make the kind of money he was making. I didn’t understand at the moment, but I do now.”

Bobby’s been telling me for two decades that his music crosses over rather than crossing out. During our most recent interview I said to him, “You’re as black as any blues artist, and I’ve been studying blues for 50 years or more. Where does that come from? I mean you have an amazing ability to write and take people like me into a world we never knew, and it’s a beautiful thing, and I love you for it. I love you for it.”

“You bring tears to my eyes,” he responded. “Nobody has ever said to me what you just said. I’m a black man. For you to understand that about me, you are the first person to ever say what you just said to me. Because I’m a black man, you understand that.”

It has never been easy. “I thought when I went to Chicago, I would be free to go where I wanted to, stay where I want to, speak when I want to, sleep where I want to.” His first trip north landed him in a little township called Robin, Illinois where some black people were. “I got a job there playing for a white club that I thought was a big club compared to Arkansas juke joints, but I had to play behind a curtain in the back where they wanted to hear my music but didn’t want to see my face.

“Now, that stopped me because my head was heavy. If I went to Chicago, Illinois I was gonna be a free (agent) and I found out I wasn’t free at all. I thought I was going to a free country, free town, free state, and I found out the same thing there (that I had in the south.)

“At that time, I didn’t understand it. I had tears in my eyes when I understood it overall. What’s disturbing about the whole thing is that out of all things that have changed some things remain the same. That’s disturbing.”

Bobby’s mother was white and his father black. “My mama was blonde with blues eyes. When I went to school, my mama took me to school, but she had to be my babysitter. I didn’t understand that as a kid, ’cause she couldn’t be my mother. My dad was her chauffeur. That’s the life I lived as a child ’cause she had to babysit me. She wasn’t my mother until we got home. She was his wife when we was home only.”

I asked Bobby what his mom did to help him not hate white people.

“When I look at the white people, I once hated ’em, but I believe I had a reason to. When you look at the other side of it, when my mom grown up, that’s my mama. I was damned if I do, damned if I don’t. What are you gonna say? That’s my mama, and I have some black slaves in my bloodlines. That’s my music. My mama was 33 years old, and I remember her dying her hair and putting sweat on her face to look darker so she would blend in like she was black.”

When Bobby was 14 years old, he painted a mustache on his face so that he would look older. Did he ever think that he would come this far?

“No! No! I thought that was the end of the line for a minute. I thought to myself, ‘What’s the use?’ But thank God I kept going. I dusted myself off and kept going. That’s my trouble now. That’s why I wrote the book I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya, because I wanted people to look at my life and know that about what you should do.”

How does somebody as talented and popular as Bobby reconcile how so many people treat each other in this world?

“I reconcile it because we all lack knowledge. Some don’t treat you well because they were taught not to treat you well at all. But my thing is, I have it in my soul about everyone. Most people don’t learn because they don’t know what they’re doing.

“I’m a blues singer (but) I’m a Biblical study. Not religious, but a Biblical study, and I know one thing: I still have hope. I’m still enthused by what I do and the way I do it. I have fallen down, and I’m probably gonna fall again. If I do fall, I get up and dust myself off again and don’t give up. That’s what I want people to see in Bobby Rush. If Bobby Rush can do this as a country boy, you can, too. Moses went through it. Christ went through it. A lot of people go through it, and when I think about what it could have been, I’m so thankful for what it is.”

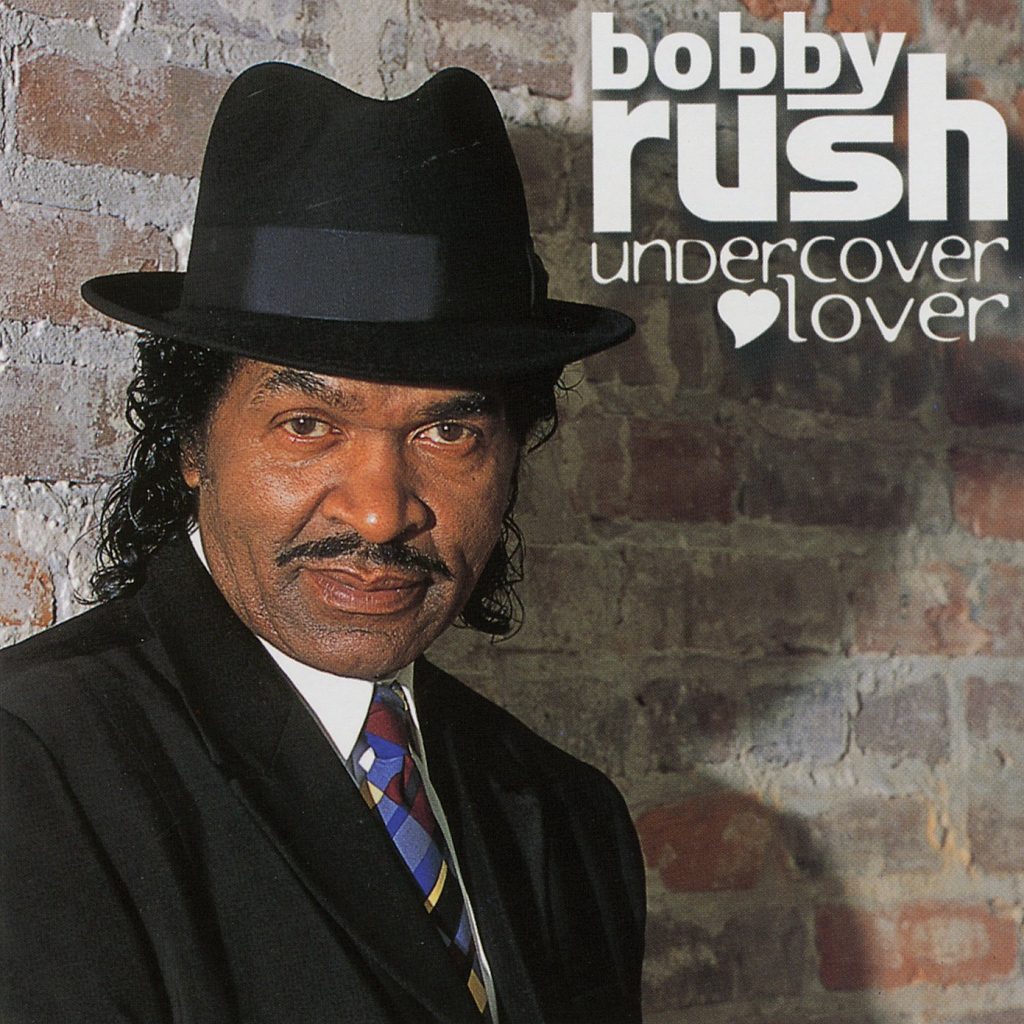

Bobby has recently re-released an updated version of his album Undercover Lover. “Undercover lover is like a black saying. I was speaking about it like the FBI, under cover but the other side of that is like undercover is the sheet under the cover. There’s two meanings to that.”

He also produced Classy Woman, an album by Mizz Lowe, the hoochie girl in his shows. “It came together because of the relationship we have, and I wanted to make sure she got the best out of what she was doing, and I’m hoping she doesn’t give up with the ups and downs and the (problems) she runs into with her life because that’s part of life, a lot of ups and downs.

“I just hope that somewhere down the line when things come hard and don’t work out, she won’t give up. I want her to tough titty, to say I’m gonna do this rain or shine. I want her to be real tough with the ups a downs that hit her life in the face. She won’t give up. (She’ll say) ‘I’m gonna do this rain or shine.'”

I asked him if was hard for Mizz Lowe to make the jump from being the hoochie girl to being a singer with her own album? “I think it was hard deep inside because I don’t think she really wanted to be a dancer. She wanted to be a singer. That’s what she wanted to be. It’s a good album. It’s produced well. She’s written well. She performs it well. She’ll get there!”

Bobby has become closer to Buddy Guy in recent years. Like John Lee Hooker, Buddy and Bobby are legacies, seniors in a genre that respects experience. Bobby was the first guest performer at Buddy annual residence concerts this year at his club Legends in Chicago.

“I just love Buddy Guy. I love his spirit. He keeps that club because of what he wants to do for other musicians. He keeps it because that’s his way of giving back to other musicians. That’s the way he do. He’s that kind of person. He’s such a great guy. He’s such a friend. A great individual. Both of us were 50-something years old before we made any real money.

The three Grammys have fulfilled Bobby Rush’s bucket list. “The Grammy kind of took off my bucket list. And I’m doing some things with my family I didn’t do in the past because I didn’t let them because I didn’t have the opportunity to do the things with them I wanted to do. I had to do some things in place I wanted to do, personal, financial things that I’ll be able to do. I was away from my family a long time – working 250 days, sometimes 300 shows a year.”