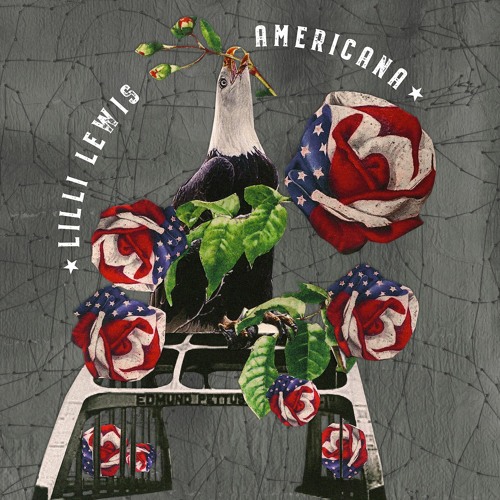

“Lilli, it’s great to hear your voice.” I have never commenced an interview this way, and I hear the words spilling out of my mouth faster than I can think. I realize it’s because I’ve been immersing myself in her singing voice — through stereo speakers, car speakers, and headphones. I feel lucky to catch this composer and producer, who’s been trained as an opera singer and classical pianist, at this stage of her life and career. Lilli Lewis is releasing her third Louisiana Red Hot Records album, Americana: not just the sterling sound of her country soul circling back to the dirt road she grew up on, but a true roots album that has the name it does because its stories and sensibilities are foundational to American music.

“It’s as much about the music as it is about the story,” the Athens, Georgia native explains to me. “In the genre, a lot of stories get left behind. I wanted to give voice to some stories that might not be included in the lexicon of American stories, and yet we’re listening to them every day.” Along the way, musically and otherwise, she started to realize that what Americana means depends on who you are asking.

“I feel like my whole life has been a pivot between my father’s 150-year-old hardwood floor church and this high art that was kind of the refuge of my youth.” Those two pivot points guide her no matter where she lives, but her current home of New Orleans is where the seams come together naturally. “I think New Orleans gets this bon temps rouler reputation, but music is religion here. And we have real masters here. You bring elite artistry to the antithesis of that when it comes to community, and that’s what you have here. It’s really a miraculous kind of circumstance. I feel like this is where all the pieces that I was kind of pivoting between came home to themselves. I feel like I found my voice here.”

The other coast played no small role in her evolution of sound. In the early 2000s Lilli ran away to Boston as a classical singer to plug herself into the Cambridge folk scene, a “zenith for women singer-songwriters,” such as Jennifer Kimball. “I think the reason Boston had such an impact is because you had the New England Conservatory, which meant that there were a lot of classical musicians around, but then also a lot of really well accomplished jazz musicians. And then you had Berklee. It was the perfect environment for my weird little music to emerge, but then I found myself missing the vibe of the South.”

Aside from an a capella record she made back in 2008, Americana is the most her album, she says, and the least influenced by the environment. That is to say she had the chance to meditate on what she calls orphaned songs over the span of many years, with a couple born in early 2020. Co-produced with Mark Bingham (Elvis Costello, Hal Willner, Allen Ginsberg), guest artists include cellist Rick Nelson (Afghan Whigs, Polyphonic Spree), singer-songwriter/fiddler Gina Forsyth, and blues singer Lady A.

“My American Heart” is the song that actor Mandy Patinkin (of Inigo Montoya fame) remarked is “like listening to light.” And then there are the songs that threaten to tear a hole in the space-time continuum. “Copper John” is the kind of song that stops you in your tracks the first time you hear it before a single word is sung, and what Lewis calls the orphan song from the album. The words join the weighty atmosphere of the music: “In the city of unseen prophets just over the hill/ There’s an army of vagabond watchmen at the citadel/ In secret they walk among us hidden in plain view/ If they happen to see something in us they might reveal a thing or two.” Then come the goosebumps, and if you’re not careful, swollen tear ducts behind your shades. Because categorical works of beauty hold that kind of power.

“When ‘If It Were You’ and ‘My American Heart’ were born, I was like, ‘Maybe this is a chance for me to finally play this song.’ I have carried that song around with me for maybe 15 years now.” For a long time people expected Lilli to play blues and R&B. “I kept trying to find a way to those languages and figure out how they speak to me. When I was in New Orleans, that really did start to show up for me. But I called it orange music, like the distant, more sober cousin of the blues. But what about all of these Americana songs that had kind of fallen off the vine along the way? Because people didn’t want to hear it from me, or it just didn’t have an audience where I was living. So when COVID hit, I didn’t have to worry about them anymore. I could do all of the songs that I couldn’t do before that didn’t necessarily work in the clubs.”

“Wrecking Ball” funks the funk out, but it does what Americana does best in its chanty refrain. The lyrics contained in that uptempo groove are that of exhaustion, truth be told, about a just society looking different than we think it should. “It’s an older tune. We usually do it as a rock tune. But it’s never found a home. The band is always like, ‘Can we do it now? Can we do it now?’ We always demo it whenever we go in to record, and it never makes the record. And so I was just like, ‘What if we take it to Muscle Shoals, bring it back and see if it makes the cut then. So that’s where ‘Wrecking Ball’ comes from. Once George Floyd was murdered and the world responded to it in the way that it did, all of a sudden the album was no longer just a vanity. It was me doing the songs that I wanted to do, that nobody would let me do before.”

Until everybody’s basic sense of dignity and safety are treated as a birthright, we don’t have a just society. “So you try to put it in a song and see if you can get people to dance to it.”

Lilli’s vocals are to “Piece of Mine” what Lead Belly’s are to “In The Pines,” cutting about as deep as the knife can go but telling an even deeper story. Keith Richards would tell you some of the best songs come to you like a ghost in the middle of the night. Lilli too can attest. “There’s another orphan one. This queer, dusty, squinty-eyed lady showed up and told me her story. I realized that we don’t always think about the fact that we’ve been here all along, us queer folk. We’ve been in every space. We’ve been in rural spaces. We’ve been in urban spaces. We have been here this whole time, but we’ve borne an awful lot of pain. I wanted to bring that voice forward. I’m glad it resonates.”

On “If It Were You,” Lilli is connected to the child’s journey, sending a powerful message in probably her most dulcet tones. “The child doesn’t really know what all’s going on. They don’t know that everything is falling apart. Then you find yourself following whatever the adults in your life tell you to do. You’re going through this winding path and it’s exhausting and terrifying. I figured out that I had been that child. When I got to the second verse, I had no intention of telling my own story. And then it just kind of came out that way. When it did, I had no intention of singing it.”

“A Healing Inside” is heavily influenced by the historically significant ensemble Sweet Honey In The Rock. The a capella hymnlike song features Lady A contributing vocals “longing for justice.” The blues legend knows a thing or two about how performative allyship can hurt the people it’s intended to support, and is herself still searching for justice over a year after she countersued the country trio with the same name for copyright infringement.

“It’s the ghost memories of our feet on that hardwood floor, because at the beginning of the service, for 30 minutes, we would do this moaning intonation thing and stomp our feet. That is still the most magical music in my body’s memories. That experience is still the most potent. So I’m always reaching back to that space because I feel like so many beautiful, powerful restorative things can emerge from that space. ‘A Healing Inside’ I actually wrote in the middle of this eight-year journey with trauma work. I have what I need inside of me. And again, it’s another one that nobody would sing with me. Then we’re in the middle of this pandemic, and I find myself in a self-help group for black women musicians. I tell them that I have this song and they’re like, ‘Oh, it’s beautiful. Let’s sing it.’ Now it has a whole different context, for justice. I have all these amazing women, including Lady A. I was outrageously honored when she decided to hop on that track. That’s the heart of the record for me.”

Another important reason she calls the record Americana is to contemplate the fact that if a white artist were to sing in those styles, they would be celebrated. “Look how versatile they are. Look how much they understand American culture.” It’s a concept she sagely describes as not much different from the social engineering and segregated status of race records, an industry marketing term invented in the 1920s. “That’s not what genres should be. There is such a thing as zydeco, and there is such a thing as polka. But if you use genre to orient your audience towards segregation, you have a fundamental problem. The whole point is that black-informed music has been in these genres from the very beginning. Every major genre that’s come up, specifically on American soil, has had black music at its root. I mean black American music; I don’t mean just Africa. You take a Roy Rogers or a Johnny Cash, the Carter family — all of these major institutions in the evolution of folk, country… All of those people were either singing songs that they took from the black church, songs that they learned from a black man who worked on the railroad — all the way up to Elvis Presley.

“When you take that out, you’re only telling a fraction of the story. Music all over the world is used for emotion regulation, for problem solving, for community building. It’s an amazing technology built and wired into the oldest part of our brain. And what did we do? We segregated it. My people have been on this land long before it was called America. My people have been both slaves and free; black people and white people; Indian people from India; and people from this land. I am all of that. I’m the whole story, and that’s why the album is called Americana. If you make it your own, that’s what music is. But you don’t go back and tell somebody they’re not entitled to their own story.”

A year ago, Lilli was invited to speak on an Americana Music Association panel about black equity in Americana. “We did two of them that year. The first got like over 50,000 views. It was in Rolling Stone and everything. And it was interesting; everybody on that call for the most part felt like they were coming out as being black.” As VP and Head of A&R of Louisiana Red Hot Records, Lilli urged, “We have to build businesses. We have to build press outlets that don’t discriminate. We have to build radio shows that don’t discriminate. Occupy any space that you feel that you’re not present and represented.” This year, one year later, Rolling Stone included Lilli in their AmericanaFest 2021: Best Things We Saw piece.

She tells me, “We had up until that point spent a lot of bandwidth protecting that industry from our blackness, and our bookings were dependent on our ability to fit in. That’s why you can have an amazing talent like Charley Pride apologizing. If he was anything like my father, he was as country as he appeared to be. When I moved to Louisiana, it was the first time since my very young childhood when the KKK was active; it was the first time I noticed that the black people were not making eye contact with white people.”

Lilli is also co-producing the inaugural #BlackOpryFest, an intersectional virtual event focusing on contributions and artistry of African American artists in country, folk, blues, and Americana. The virtual festival and conference starts October 28 until October 30. “We are pivoting to a virtual event, and I’m going to feature live performances from New Orleans people in this conversation. Black Opry had a house during AmericanaFest. We had most of the time 30 to 50 people there, 95% black, all folk and country singer-songwriters just having a great time. Since then we’ve had our first Black Opry Revue in New York. So what we’re going to do is do a virtual Black Opry Revue during Black Opry Fest. All our headliners are sending in videos. We’ll have conversations about Americana Fest. We have slated some professional development programming from the Recording Academy, and we’ll do an award ceremony.

“We’re going to feature people like Anita (Lady A), Rissi Palmer, Miko Marks. And I’ll have a CD release event during that as well. Hopefully by next year we’ll be able to do it in person. But in the meantime, Black Opry is doing installations like we did at AmericanaFest. They’re going to do it again at Folk Alliance in February. It’s these spaces where black artists tend to feel marginalized. We’re going to have this support there for them through the Black Opry house — things that naturally happen for mostly white artists in those spaces, like collabs, connections, and co-bills.

“Folk Alliance in particular, they’re definitely working on it. In the meantime, we’ll be there to have that support. The great thing about it is that when we gather in numbers, our presence is not politicized. The thing about the folk and Americana communities is that they try to be progressive. That means that our PR is a political thing, but some of us love music and we just want to play our songs. In this context it doesn’t have to be politicized. It can just be about the music. And I like that.”

Being raised a classical musician has given Lilli an astute ear tuned towards hearing something from the turn of the 20th century, for example, like it’s new. If she finds a recording from the 1800s that sounds just as alive now as it did then, she feels the direct lineage immediately. “My whole world exists pre- all these little pockets of genre because I feel where it came from. When I listen to Lead Belly, I hear these crazy melodies and cross-relational chord changes. Where do you go to get the weird blues? Where do you go to get the weird folk that was going on with an artist like Lead Belly, whose language is that exploratory? And would you claim it?”

Her nomenclature, folk rock diva, is self-explanatory and also accurate. The traditions built up somewhat piecemeal, but she’s quickly become all three of them. There are moments when you’re listening to artists like Mariah, Whitney, and Aretha, and their melismatic singing seems like the musical version of trapeze stunts. I now add Lilli to that rarefied list. If you were to ask her the parallels of gospel and opera, for example, she would tell you there’s a reason Aretha Franklin was invited to sing “Nessun Dorma.”

“Folk rock diva was born when I was in a folk rock band, like an indie band. I was the only black member. I had this classical background, and the band just started calling me the diva. We would do these epic numbers that felt more like arias than folk rock. That’s partly where it was born. We used to say it’s folk because we sing songs for the people, and it’s rock because sometimes we get loud about it. And if my hair is big enough, the diva part is self-explanatory. But in recent years I’ve become attached to all three of those words for a number of reasons.

“The folk part, because I want to keep it real. I want to keep everything grounded. I don’t want to lose track of my reasons for making music. I want to keep it relational, and I don’t want to get too involved with overproduction. I want the song to work in its smallest iteration. That’s where the folk sentiment comes from for me, remembering my dad in the cotton fields and the dirt road I grew up on. The rock is necessary because sometimes my feelings are big enough that I have to get loud. I retain permission at all times, because they tried to shove me into jazz and coffee shop type folk. And I’m like, no, I do have to get loud sometimes.”

The diva part, she says, has gotten a little bit interesting. When you interrupt the sacrosanct white male role of Americana, as with the blues, some grow increasingly concerned with educating you on what the genre means. Americana represents artistic freedom emerging from a lifetime of being surrounded by people trying to keep her in her place, and sees Lilli walking tall through fire without blinking. “And I’ve decided that I’m not doing anybody any good by co-conspiring with that. The diva part is reminding me, ‘Lilli, always check in with what you think your highest possible purpose could be and do your best to do that.’”