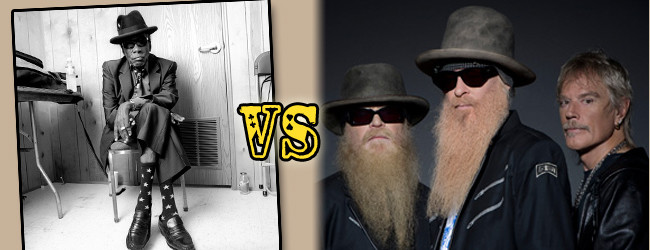

This is the latest article in the popular Blues Law series by lawyer, author, and radio personality Brian Lukasavitz, “The Blues Attorney”, that explores interesting and landmark law cases related to the blues genre.

Let’s begin by saying that it wasn’t John Lee Hooker himself that sued Z.Z. Top, but rather Hooker’s songwriting partner and copyright holder, Bernard Besman. The classic boogie-style blues riff that was first recorded by John Lee Hooker in the form of “Boogie Chillun”, in 1948, became the basis for the court case La Cienega Music Co v. Z.Z. Top in 1992. Hooker had long acknowledged that his sound was far from original. He has often attributed his musical style of “boogie” as his version of the boogie-woogie style he heard growing up in Mississippi. Hooker also made public statements that he, personally, was not involved in the lawsuit against Z.Z. Top and that he would not gain financially in anyway. Additionally, he said he respected Z.Z. Top and that they were mutual fans of each other’s work.

So, how did this copyright infringement case over the classic riff of “Boogie Chillun”, “La Grange” and countless other blues and rock tunes come to be?

In 1992, Besman (and his company La Cienega Music Co.) brought a claim against Z.Z. Top and their publishing company, Hamstein Music Company, over the 1973, Z.Z. Top hit “La Grange”, which he alleged was infringing the copyright of the Besman-owned song “Boogie Chillun”, published in 1948, a re-written and published version in 1950, as well as another re-written version in 1970. (An important fact is that John Lee Hooker had assigned all his rights to this song to Besman, who later registered the copyright with the U.S. Copyright Office in 1967.)

Z.Z. Top argued that though “La Grange” was based on the “Boogie Chillun” and John Lee Hooker’s style of boogie, that the elements taken and the song itself were considered public domain. This argument, which ultimately was convincing to the court, and the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, was that under the Copyright Act of 1909, “Boogie Chillun” was no longer protected by copyright.

The court rule that under the 1909 Copyright Act, an “unpublished” song was entitled to protection under what is known as State “Common-law Copyright protection”, until either it is published or it is registered with the U.S Copyright Office. Although the Copyright Act is unclear as to what constitutes “publishing”, other than publication of sheet music, the majority of courts have agreed the sale of recordings to the general public rises to “publishing” for purposes of common-law copyright. Under the 1909 Copyright Act, an author of a creative work, is entitled to 28 years of copyright protection, with the option to re-register for an additional 28 years. The court also found, under the 1909 Copyright Act, that once a song is published and the author has failed to register the work with the U.S Copyright Office, the song immediately, and irrevocably falls into the public domain. In this case, the Courts found that Besman had failed to properly copyright the song in a timely manner, so the early versions of the song were considered part of the public domain, which meant Z.Z. Top was not liable to Besman or La Cienega Music Co.. So for all the boogie-lovin’ blues and rock fans out there….if you got that boogie-woogie in you and you gotta let it out….do it….a-how-how-how-how!!!

On a side note, the length of copyright protection to a registered work has changed twice since 1909, first with the Copyright Act of 1976, and again with the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998 (A.k.a. The Sonny Bono Act).