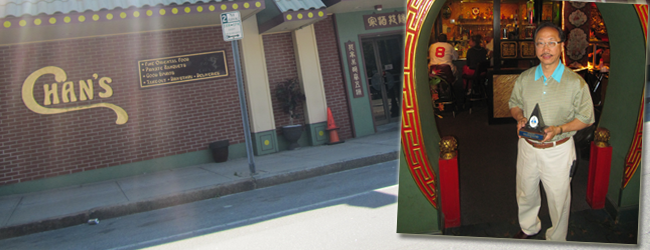

Situated between a paintball shop and the Providence-Worcester railroad in historic downtown Woonsocket, Rhode Island is the most inconspicuous blues club in America. In fact, if you told someone to locate it, and gave them the street but not the name, they’d probably drive right past the Main Street venue. That’s because this New England blues mecca is disguised as Chan’s Oriental Dining.

Known affectionately as the “Home of eggrolls, jazz and blues,” every blues artist from David “Honeyboy” Edwards to James Cotton to current blues-rock hero Joe Bonamassa has made an appearance. “I had Joe a few years ago,“ said owner John Chan. “Before he got too big. He loved it. He had a ball. Now I can’t afford him.”

Originally owned by Ben Chan, John’s father, Chan’s began offering music in 1977, a few years after John Chan – he of the Salvador Dali mustache – returned to manage the restaurant after graduating from college. What started off as strictly a jazz club would soon see such limitation lifted. Thirty four years later, blues reigns supreme. There’s still jazz now and then, but blues takes the cake, even if oversized acrylic paintings of jazz greats Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughn flank the stage of the Four Seasons Banquet Room, and the smirking visage of blues legend Muddy Waters is relegated to a corner of the room, behind the bar.

Even so, Chan’s was honored this past February with the Blues Foundation’s “Keeping the Blues Alive Award,” the only blues club in the country to receive such an honor in 2011. “I’m proud to share this award with all the loyal fans, the amazing musicians that have supported Chan’s in the last 34 years,” said Chan during an interview with the American Blues Scene. “They’re the ones who make it possible.”

Many musicians have made Chan’s their home away from home. Blues guitar whiz Ronnie Earl has played three to four times a year for the past half decade, and Tab Benoit, considered the prince of the Cajun blues, has played the restaurant so often that he and Chan have become great friends. “He plays two nights and then we go golfing,” said Chan. Leon Redbone, John Hammond Jr. and Mose Allison, to name a few, are also regulars.

“Musicians love coming here because of the hospitality. I treat them like they’re coming into my home,” said Chan, who also treats not-so-famous guests like they’re somebody special, often seating them himself rather than staying put behind the front desk, where his blues award sits behind glass.

American Blues Scene took in a recent Friday performance at Chan’s featuring Alligator Records recording artist Guitar Shorty, a 70-something-year-old blues artist who, like 70-something-year-old blues legend Buddy Guy, can give you down home blues just as easily as he can wow you with Jimi Hendrix-like blues fireworks. Shorty loves the intimacy of the Four Seasons Banquet Room, which comfortably seats 125. “I like being close to my fans. It shows them that I’m human, not some image in the distance,” said Shorty. “If you’re far away, they can’t tell who you are and if you’re real or not. But when they’re close, they can touch you. They know you’re real.”

As is usually the case with his shows, Shorty left the stage to sing and play amongst the crowd. However, he really didn’t need to walk around the tables filled with people still finishing off their Five Spice Shrimp or their Mandarin Duck. Chan’s had him close from the start.

The musicians didn’t always play the Four Seasons Banquet Room. That’s because Chan’s didn’t acquire the space, a former bank, until the mid-1980s. The dining room used to be the entertainment space. However, the banquet room, with its salmon-colored walls and bank vault door which now houses fortune cookies, opened in 1986, and two heavy doors do a pretty darn good job of keeping the music from customers in the lounge and dining room that just might be looking to dine without a dose of the blues. There’s no telling why they wouldn’t want Chinese food or drinks without the blues, but that’s their loss.

Those that want music with their meal may purchase show tickets in addition to their dinner. An upcoming appearance by Hammond next month is $22 for the 8 p.m. show, $15 for the 10 p.m. show, or $25 for those that might want to catch both performances. As for the food, there are many meals for less than $10 (and portions are very generous) and only a handful of dinners are in the $12 and $13 range, such as Lobster Kew, Ginger Shrimp, Mongolian Steak and Polynesian Delight.

If Chan wasn’t already the coolest Chinese restaurant owner for featuring blues acts at his place, it turns out he also has Hollywood connections. That would explain the posters of numerous Farrelly brothers films that one first sees on the walls when they enter Chan’s – “There’s Something About Mary,” “Dumb and Dumber,” Stuck On You, “Shallow Hall” and others. Chan’s been on the set of “There’s Something About Mary” and is acknowledged at the end of “Me, Myself and Irene,” which starred Jim Carrey, with a still of his scene that was cut from the film. Although a scene he shot with Cher for “Stuck On You” was also scrapped, the Farrelly brothers gave him a fake Oscar statue for “Best Actor Cut From the Movie.”

However, Chan doesn’t always see his roles get scrapped. He actually appeared in 2005’s “Fever Pitch,” which starred Jimmy Fallon and Drew Barrymore, and also found his way into the Showtime series “Brotherhood,” which was filmed on location in Providence and other parts of Rhode Island. “They asked me to play a Chinese restaurant owner,” said Chan. “I said ‘I think it’s a little bit of a stretch but I think I can do it.’ ” Chan said the Farrelly brothers (Peter and Robert) are good friends who grew up in the neighboring town of Cumberland.

“Their father, Dr. Bob Farrelly, is a big fan of Leon Redbone,” said Chan. “The whole clan would come whenever Redbone is in town.”

Forty-eight-year-old Peter Neff, of Chepachet, RI, has been coming to Chan’s “every week for 25 years.” He comes no matter who the act is. “John gets people that nobody else can draw,” he said. “Look at the live CDs that have been put out from here.

Neff added that other musical venues have capitalized off Chan’s success. “Narrows Center for the Arts in Fall River [Massachusetts]; without John they wouldn’t be here,” said Neff. “There wouldn’t be any Stadium Theatre [up the street from Chan’s]. They’re piggybacking his schedule. They couldn’t have pulled these people into the area. John provided a cultural anchor for Woonsocket.”

He added, “Musicians would have had nowhere else to play for 20 years without him. The whole northwestern corner of Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island, he held it together.”