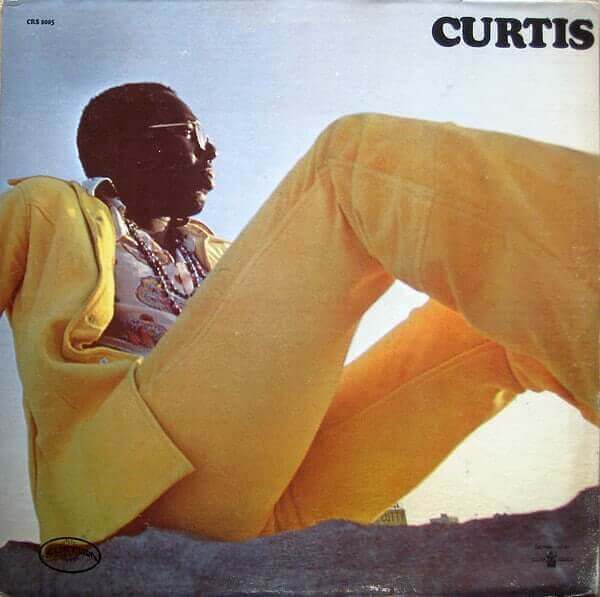

Fifty years ago this month, Curtis Mayfield released his first solo album, simply titled Curtis, a landmark recording that busted open the doors of its genre and captured the essence of its era like few albums ever have. It was Mayfield’s first album after splitting with the Impressions, and it remains a work of stunning brilliance, with rhythms that prefigured hip-hop (see Kanye West’s “Touch the Sky,” which samples Curtis’s “Move on Up,” for one example), and gutsy, gripping lyrics that widened the vocabulary of popular music.

Perhaps most importantly, Curtis is a master class on the effects of American racism and our refusal as a nation to come to terms with it. After half a century, it still speaks to the American experience with startling insight and damning truth. It is both a prediction of and an explanation of the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor (and too many others), the resulting protests and riots, and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The album came at a time of great social unrest. The ’60s had ended in a bloodbath, with nationwide riots in ’67, ’68, and ’69, plus the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. Musically, the new decade began with the Beatles splitting up. Six months later, both Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin were dead. Meanwhile, Nixon was halfway into a presidency he had won by campaigning with racist dog-whistles and calls for “law and order.” While Nixon dismantled the charred remains of the civil rights movement, a Time magazine poll in 1970 found that more than two million black Americans counted themselves as “revolutionaries” and believed only a “readiness to use violence will ever get them equality.”

Times were dark, desperate, deadly. Curtis captured it all.

The album also came at a high point for Mayfield. Two years prior, he had turned down half a million dollars to renew his contract with ABC, opting instead to start his own label, Curtom. He released three hit albums with the Impressions on Curtom before deciding he was tired of the endless slog of album-tour-album-tour. He quit the band in mid 1970, hoping to devote more time to the label and turn it into Chicago’s answer to Motown. In addition to being one of the most successful musicians of the 1960s, by the time he began recording Curtis, he was a business mogul.

He had modest expectations for his solo career. As he said at the time, “I thought I’d go home and be a businessman. I hoped [Curtis] would maybe sell 25,000–50,000 albums, which, of course, would have been an asset to help the company.” Instead, the album sold more than half a million copies. It went to the top twenty on the pop charts and hit the number-one spot on the R&B chart (music charts back then, like much else in America, were still segregated). But it did so much more. With Curtis, Mayfield defined the trajectory of 1970s soul. He did this by dealing with the reality of race in America more directly, honestly, and boldly than anything that had come before.

The album opens to the sinister strains of “(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Below, We’re All Going to Go,” the bass growling menacingly as a woman reads from the Book of Revelation and Mayfield shouts, “Sisters! Niggers! Whiteys! Jews! Crackers! Don’t worry. If there’s a hell below, we’re all gonna go.” Then he lets out a demonic howl as the groove kicks in. Sly Stone had recorded “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey,” in 1969, but “Hell Below” was among the first mainstream recordings to use the word, setting the scene for both the unflinching honesty of Mayfield’s solo career and the hip-hop age it helped spawn.

This was not the Curtis Mayfield of “People Get Ready” and “Keep on Pushing.” He had watched his people march for their rights only to be met with state-sanctioned terrorism. He had felt the hope of the movement crumble in the wake of assassinations and FBI counterintelligence operations. He had seen his people numb their minds with heroin to escape the hellish pain of reality. As always, he sang about it: “Everybody smoke, use the pill and the dope / Educated fools from uneducated schools / Pimping people is the rule, polluted water in the pool /And Nixon talkin’ ’bout don’t worry, he says don’t worry / But they don’t know, there can be no show / And if there’s Hell below, we’re all gonna go.” He didn’t just have his finger on the pulse of the new decade; he was in the bloodstream.

Curtis follows this devastating eight-minute opus with “The Other Side of Town,” another brilliant study of American racism, this time dealing with the effects of segregation and the racist housing policies that created projects like Cabrini-Green, where Mayfield grew up. His lyrics are again poignant and heartbreaking: “It’s hard to do right in this filthy night / Just plain simple comfort is completely out of sight / My little sister, she hungry for bread to eat / My brother’s hand-me-down-shoes is now showing his feet / Ghetto blues shown on the news / All is aware, but what the hell do they care?” Mayfield’s understated vocal belies the anger of the lyrics and the heaviness of the orchestration.

Next, the mood lightens on the gorgeous ballad “The Makings of You,” which shimmers with strings, horns, and harpsichords, making breakneck changes between a whimsical European waltz and deep Chicago soul. It is one of the most beautiful love songs Mayfield ever wrote, and in context of the album, it plays like a balm to the heaviness of the songs before it. It is a way of saying there is more to the story than suffering. There is also love. “Add a little sugar,” he coos in his signature falsetto, “honeysuckle, and a great big expression of happiness… These are the makings of you.”

But the focus returns to the heaviness on “We People Who Are Darker Than Blue,” which is perhaps the crowning achievement of Mayfield’s entire career. It starts as a slow blues, as he confronts society’s expectations. “We’re just good for nothing they all figure,” he sings, “A boyish, grown up, shiftless jigger.” He confronts the complex history of skin color, singing, “High yellow girl, can’t you tell / You’re just the surface of our dark, deep well?” Most powerfully, he confronts the white world’s version of history: “Pardon me, brother, as you stand in your glory / I know you won’t mind if I tell the whole story.” Mayfield delivers one of his most impassioned vocals as the A-side ends in a devastating flourish of horns, harp glissandos, and cymbal swells.

If Mayfield proved he could be an incisive commentator on the A-side, he proved he could still be a damn good motivator with “Move On Up,” the opening song on the B-side. Rhythmically, it is perhaps the most complex song he ever wrote, and it contains a drum break that predicted the rise of hip-hop in the next decade. Two other things are especially important about the song. One, he chose to put it on the B-side and start his first solo album with the super-heavy, brutally honest “Hell Below.” The decision showed Mayfield’s guts and merit as an artist. From a commercial point of view, it would have made more sense to hook listeners first with the positive, infectious ear candy of “Move On Up” and then lay down the serious message. And two, he went even further by releasing “Hell Below” as the first single, instead of “Move On Up.” Again, the message came up front, and the audience responded. “Hell Below” went to number three on the R&B chart.

“Miss Black America” is the final message song on Curtis, and it is the only track that tied Mayfield to his old group. The Impressions had recorded the song for a beauty pageant of the same name in 1969, but in the context of Curtis, it takes on political and even feminist overtones, confronting society’s standards of beauty and skin color as they related to women.

Taken in total, Curtis is a sort of musical version of the Kerner Commission—the 1968 government report on the gap between white and black America, which remains one of the most powerful indictments of American racism ever created. Mayfield didn’t create an intricately researched sociological document the way the commission did, but he painted just as vivid and nuanced a picture of what it meant to grow up under American apartheid, of what it did to a person’s mind, body, and spirit. In the context of a pop album this was astounding.

It is hard, if not impossible, to think of any artist who spoke such difficult truths on such a mainstream level, and who did it as consistently as Mayfield did. Curtis was the first step in a six-year run of genre-bending, chart topping, soul searching music that included landmarks like Curtis/Live!, Roots, Superfly, and Back to the World.

Half a century on, Curtis remains the rarest of things — a work of art that is both of its time and timeless. That the music remains so vital, so exciting, so fresh, is reason to celebrate. That its message of inequality and devastation still fits us like a pair of handcuffs is reason to despair. As the Economic Policy Institute reported in 2018, “with respect to homeownership, unemployment, and incarceration, America has failed to deliver any progress for African Americans over the last five decades.” Black workers make only 82.5 cents on every dollar earned by white workers, and are two and a half times as likely to be in poverty. The median white family has almost ten times as much wealth as the median black family. Meanwhile, in the past fifty years, the number of incarcerated black Americans has almost tripled.

We seem to have a hard time in this country connecting the dots. We either cannot or do not want to recognize that these numbers are directly related to the crushing racism Mayfield sang about in 1970, which has adapted rather than disappeared—and that the racism of 1970 was simply an adaptation of Jim Crow, segregation, and lynch mobs, which were themselves an adaptation of slavery.

Mayfield died in 1998, but he would recognize our current moment. He would certainly stand in solidarity with the protestors in Portland, Seattle, Minneapolis, and Louisville. He would see Donald Trump’s racist dog-whistles, his calls for law and order, his coddling of white supremacists for what they are. But he wouldn’t let us sink into despair. He would encourage us to keep fighting. As the man himself once sang: “Pardon me brother, I know we’ve come a long, long way / But let us not be so satisfied, for tomorrow can be an even brighter day.”

Travis Atria co-wrote Traveling Soul: The Life of Curtis Mayfield with Mayfield’s son, Todd. His latest book is Better Days Will Come Again: The Life of Arthur Briggs, Jazz Genius of Harlem, Paris, and a Nazi Prison Camp.

Traveling Soul is the first definitive biography of the soul legend, chronicling his life from humble beginnings in Chicago’s Cabrini Green projects, to his success with the Impressions, writing songs that inspired the Civil Rights movement, and making his masterpiece, Superfly. It was recognized with honorable mention by the Society of Midland Authors (past winners include Kurt Vonnegut and Studs Terkel). Better Days Will Come Again is the epic true story of jazz great Arthur Briggs, a saga that races from Harlem in the Renaissance, to Paris in the Jazz Age, to a Nazi prison camp in World War II.